How a Peace Deal in Colombia Brought War on the Amazon

(Bloomberg) -- Peak burning season is approaching in the Colombian Amazon.

Near the town of El Capricho in the country’s south, cows graze among tree stumps on a strip hacked out of the rain forest. A more recently razed patch looks as though it has been shelled, the ground scattered in branches waiting to be burned off.

If there’s dry weather in the coming weeks, fires will be set to clear the chainsawed land so it can be turned into pasture, said Angelica Rojas, a local environmentalist.

“People’s fingers are itching to light the matches,” she said.

Much of the world’s attention is focused on Brazil’s dismal record on safeguarding the rainforest, yet in neighboring Colombia swathes of the Amazon are being turned into a mosaic of islands of jungle interspersed with vast cattle ranches. Unlike Brazil, this isn’t the result of tacit approval by the authorities, but the unintended outcome of a peace deal the Colombian government struck with Marxist guerrillas, which has accelerated deforestation.

Just a few minutes up a dirt road from El Capricho, in Guaviare province, is a settlement occupied by about 200 demobilized fighters and their families. They used to be the law throughout the territory; now they spend their days farming pigs and producing honey.

By laying down their weapons, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, inadvertently opened the region to the land grabbers and cattle ranchers who are tearing down the forest at a record pace.

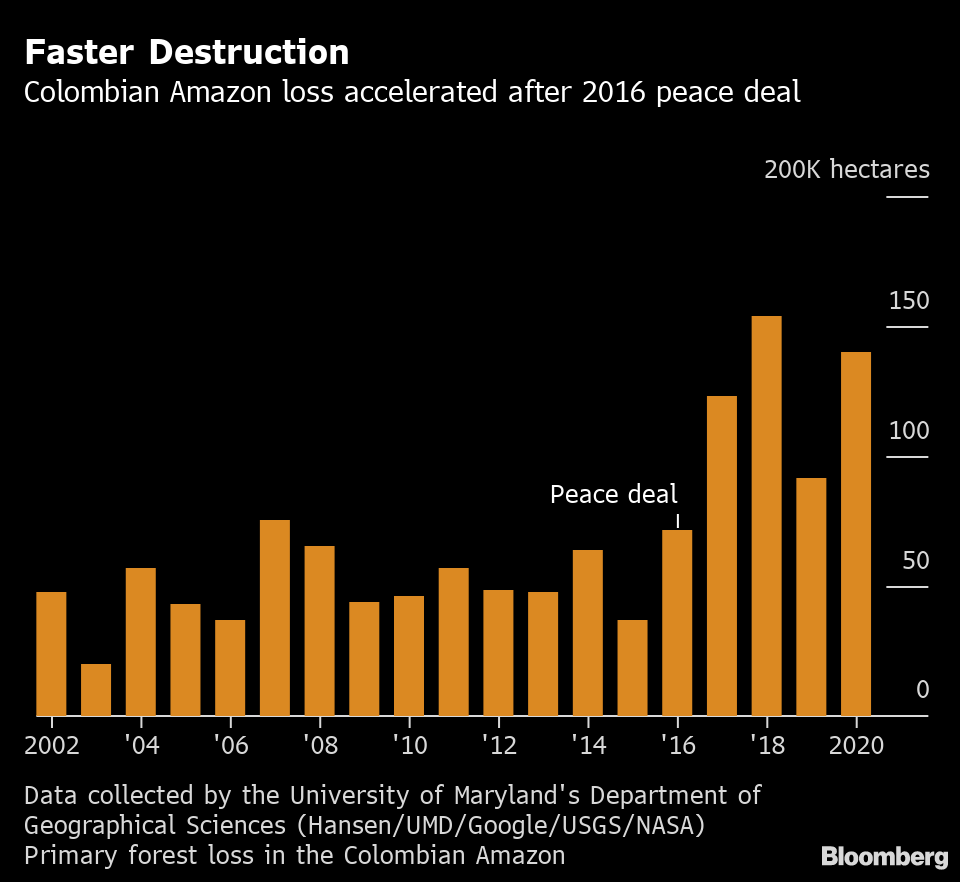

Last year, 140,000 hectares of the Colombian Amazon was destroyed, equivalent to about 20 soccer pitches every hour, data collected by the University of Maryland show. That’s more than triple the level in 2015, the year before the FARC agreed to abandon a half century of fighting.

The belt of land where Colombia’s hot, cattle-raising grasslands meet the rain forest was the FARC’s heartland, where many of its senior commanders were based. These once-elusive fighters are now a familiar sight, buzzing up and down the muddy lanes near El Capricho on motorbikes, buying groceries and taking their children to medical appointments.

Before the peace deal, they imposed punishments on the local farming community for violations of their rules. Offenses they regarded as especially serious, such as spying for the army, carried the death penalty.

The presence of a much-feared guerrilla force with a penchant for kidnapping was a brake on economic activity of all kinds, including the environmentally catastrophic cattle ranching that is now booming. In addition, the FARC imposed a ban on cutting down trees without permission, and was serious about enforcing it.

For unauthorized deforestation, a person might be fined, or made to do community work such as repairing roads, said Julian Gallo, a former member of the FARC’s seven-member ruling council.

The FARC’s defense of the Amazon wasn’t simply driven by an altruistic desire to preserve the habitat of jaguars, tapirs and tree frogs: The jungle canopy concealed their movements from the army, and the forest’s bounty served as a strategic food bank, Gallo said in a phone interview.

“We successfully survived long periods of military operations with economic blockades, thanks to the reserves of fish and wild meat,” said Gallo, who now has a seat in the senate under the terms of the peace accord.

After Gallo and his comrades handed in their weapons, the government failed to exercise anything like the same degree of authority over the Amazon region. The FARC’s rule wasn’t substituted by control from Bogota, as promised; it was replaced by something closer to anarchy.

A local army unit described the area around El Capricho as a “red zone,” due to the presence of illegal armed groups, and advised against travel there last month. Several police were injured near the town in an IED attack on a patrol last year.

“We have to recognize that the peace deal demonstrated that the FARC had a control that curbed deforestation in the Colombian Amazon,” said Geovanny Gomez, a former mayor of the provincial capital, San Jose del Guaviare, and the surrounding area.

About a tenth of the Amazon is in Colombia, where it has suffered less damage than it has in Brazil, at least until now. From 2001-2019, Colombia lost 2.7% of its rainforest, while Brazil lost 7%, according to data compiled by Rainforest Foundation Norway, an NGO.

In 2019, the government of President Ivan Duque launched Operation Artemisa, named after the Greek goddess of the wilderness, involving more than 20,000 soldiers and police in a crackdown on environmental crimes. At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow last month, Duque committed to protect Colombia’s forests and pledged that 30% of the nation’s territory would have protected status by next year.

Read More About the Pledge to End Deforestation

Huge swathes of Colombia already have such status: One national park in the Amazon region — Chiribiquete — is bigger than Switzerland. Yet protected status hasn’t prevented incomers from destroying its forest cover and filling it with cattle.

Some of the blame can be laid at the feet of so-called FARC dissidents, who became disillusioned with the peace process and returned to the conflict. In the absence of state control, they grew swiftly, their expansion fueled by profits from the cocaine trade.

While the old FARC kept a lid on large-scale farming, the explosion of cattle ranching in the Amazon gives the dissidents a chance to rake in more extortion money. And since they move around in smaller groups than the FARC, they have less need for forest cover.

The number of cattle in eight key districts where the Amazon is suffering high levels of deforestation almost doubled to 2.1 million last year from 2016, according to a study by Rojas’s environmental group, the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development.

Last year, environmentalists in parts of the Amazon started receiving death threats in pamphlets purporting to be from the FARC dissidents. One pamphlet seen by Bloomberg News said that environmental activists in the area would henceforth be considered a “military objective.” Another made the same threat against employees of Colombia’s National Parks service.

These threats are not to be taken lightly: 65 environmental defenders were murdered last year in Colombia, the most of any country in the world, according to a report by Global Witness, a London-based NGO.

The closely-related phenomena of land grabbing and cattle farming are the principal risks to the Colombian Amazon, with cocaine production and illegal gold mining also playing a role.

Cattle farming is a favorite means of laundering profits from drug smuggling, due to its cash transactions and lack of traceability, said Juan Ricardo Ortega, a former head of Colombia’s tax agency. In Guaviare, locals say that some of the biggest ranches are owned by cocaine traffickers, though their names generally won’t appear on any ownership documents.

Jose Felix Lafaurie, the head of Colombia’s largest association of cattle producers, Fedegan, says drug traffickers are responsible for the lion’s share of the destruction. They use cattle to launder money “without even worrying whether it’s profitable, let alone the environment,” he said in a letter to a lawmaker last month.

Certainly, coca — the raw material for making cocaine — used to be the main source of income for the area around El Capricho. Locals dug it up under the terms of the peace deal, but say the promised financial assistance failed to appear.

As a result, “the farmers have gone deeper into the forest to cut down more trees and plant more” coca, said Richar Ortiz, himself a former coca grower who now sells ice creams from an icebox strapped to a motorbike.

The biggest damage, however, is done by the growing demand for beef, according to Pedro Arenas, a former congressman from Guaviare who founded the NGO Viso Mutop to promote sustainable development. In November, the Ministry of Agriculture announced that Colombia had cleared the regulatory hurdles to begin exporting live cattle to Saudi Arabia, and the extra demand will boost prices nationwide, he said.

“This is an incentive for more production of cattle in any part of Colombia,” said Arenas. “And the cheapest land in Colombia for cattle is the Amazon.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GB Energy Faces New Doubts as UK Declines to Affirm Future Funds

Korea Cancels Planned Reactor After Impeaching Pro-Nuke Leader

Brazil’s Net-Zero Transition Will Cost $6 Trillion by 2050, BNEF Says

SolarEdge Climbs 40% as Revenue Beat Prompts Short Covering

EU to Set Aside Funds to Protect Undersea Cables from Sabotage

China Revamps Power Market Rules In Challenge to Renewables Boom

KKR increases stake in Enilive with additional €587.5 million investment

TotalEnergies and Air Liquide partner to develop green hydrogen projects in the Netherlands

Germany Set to Scale Down Climate Ambitions