How Europe Ditched Russian Fossil Fuels With Spectacular Speed

(Bloomberg) -- Europe’s most remarkable response to Russia’s war on Ukraine hasn’t been marshaling military equipment and billions of euros in aid. It’s been the unprecedented speed of an energy transition that in one year has nearly eliminated its dependence on Russian fossil fuels in an attempt to strangle the key source of funding for President Vladimir Putin’s war machine.

The shift has been far from the kind of climate-first transition that Europe has envisioned for its long-term future, with governments paying whatever it takes to secure liquefied sources of natural gas brought in by ships, burning more coal and ripping up some environmental plans in the process. And it’s been painful, with Europe getting hit by a roughly $1 trillion energy bill last year, cushioned by hundreds of billions of euros of government subsidies.

Still, even the most optimistic outlooks from analysts and the bloc’s own leaders at the outset of the war failed to predict how quickly Europe could move. A year ago, Europe spent about $1 billion a day to pay for gas, oil, and coal imported from Russia. Today, it pays a small fraction of that amount.

“Russia blackmailed us by threatening to cut the energy supply,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said earlier this month. “We have completely got rid of our dependency on Russian fossil fuels. It went much faster than we expected.”

Matters could have been worse, if it weren’t for Europe’s transition to clean energy that had begun in earnest years ago. That’s one reason why, even as the bloc prioritized any source of energy that was not Russian, emissions in 2022 decreased slightly rather than increasing. And there was also a significant contribution from warm weather — thanks to climate change — that cut demand for heating, and from polluting industries that simply shut down because they couldn’t afford to pay for the energy needed to operate.

But what the past year has shown is that it’s possible to go harder and faster in deploying solar panels and batteries, reducing energy use, and permanently swapping out entrenched sources of fossil fuel.

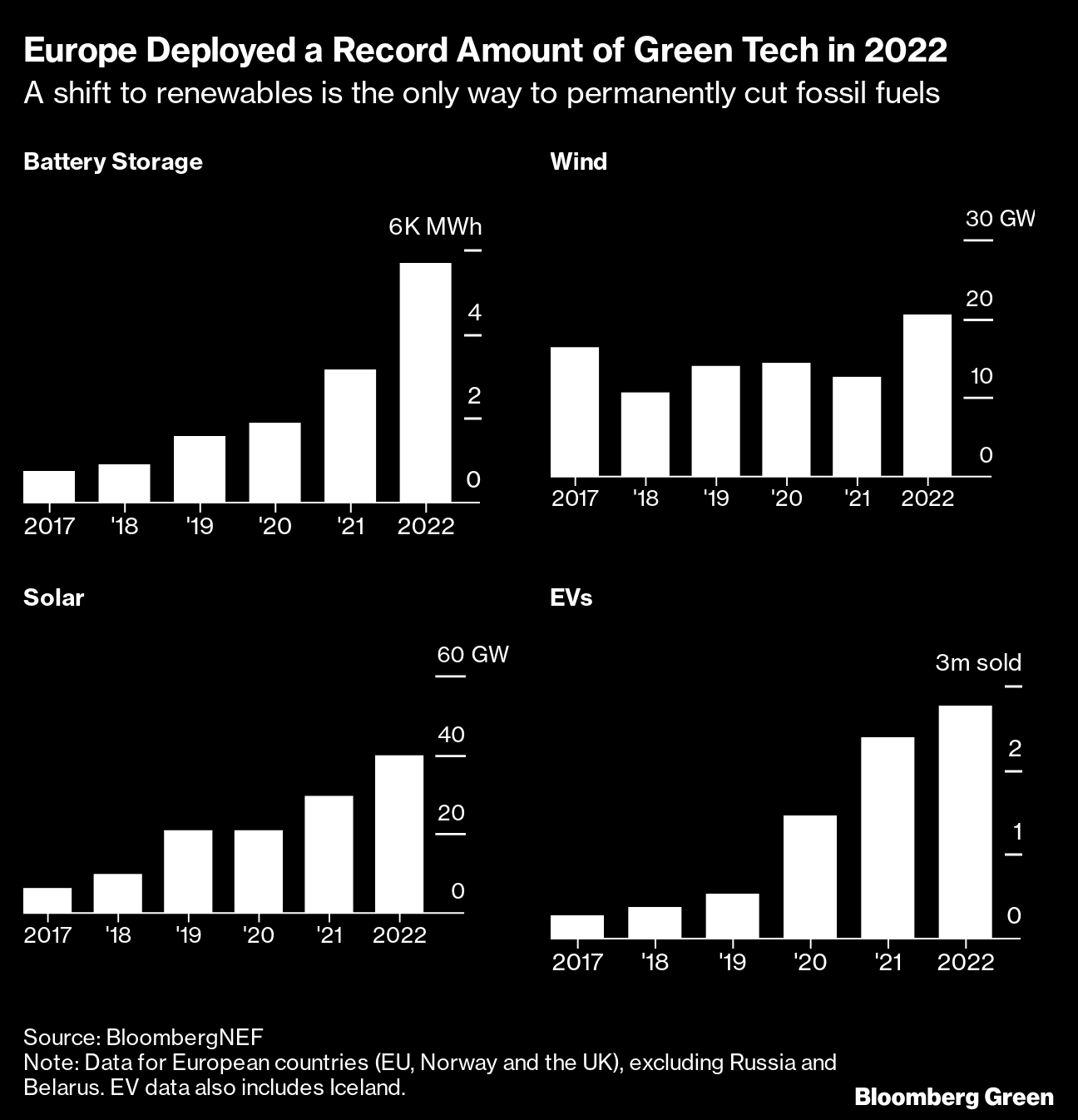

Solar installations across Europe increased by a record 40-gigawatts last year, up 35% compared with 2021, just shy of the most optimistic scenario from researchers at BloombergNEF. That jump was driven primarily by consumers who saw cheap solar panels as a way to cut their own energy bills. It essentially pushed the solar rollout ahead by a few years, hitting a level that will be sustained by EU policies.

Installing solar panels onto the roof of a home in Spain in September.Photographer: Angel Garcia/Bloomberg

Installing solar panels onto the roof of a home in Spain in September.Photographer: Angel Garcia/Bloomberg

The acceleration came ahead of the EU’s new solar incentives, which “probably haven't really kicked in yet,” said Jenny Chase, analyst for BNEF. “Everything in solar has just happened because of consumer demand.”

Many of the people who installed solar panels on their roofs added a battery as well. Battery storage rose by a record 79% last year in Europe, led in large part by the residential sector, which rose by 95%, according to data from BNEF. The increases came even as battery prices rose for the first time, leading some large-scale developers to hold off on investments.

Wind power also increased but could not match projections. Inflation held back wind more than solar, adding to existing permitting delays and regulatory hurdles that made the rollout slower than what might have been possible, according to Oliver Metcalfe, an analyst with BNEF. “The energy crisis has focused political minds on resolving some of the issues around permitting,” he said.

What Happened to Fossil Fuel?

No expansion of renewable energy was ever going to be enough to replace oil, gas and coal from Russia so quickly. Europe had for years imported large quantities of natural gas conveniently via pipelines linked to Russian fields. Cheap piped gas had long kept energy prices low and replaced more polluting coal power plants. But the invasion changed that overnight.

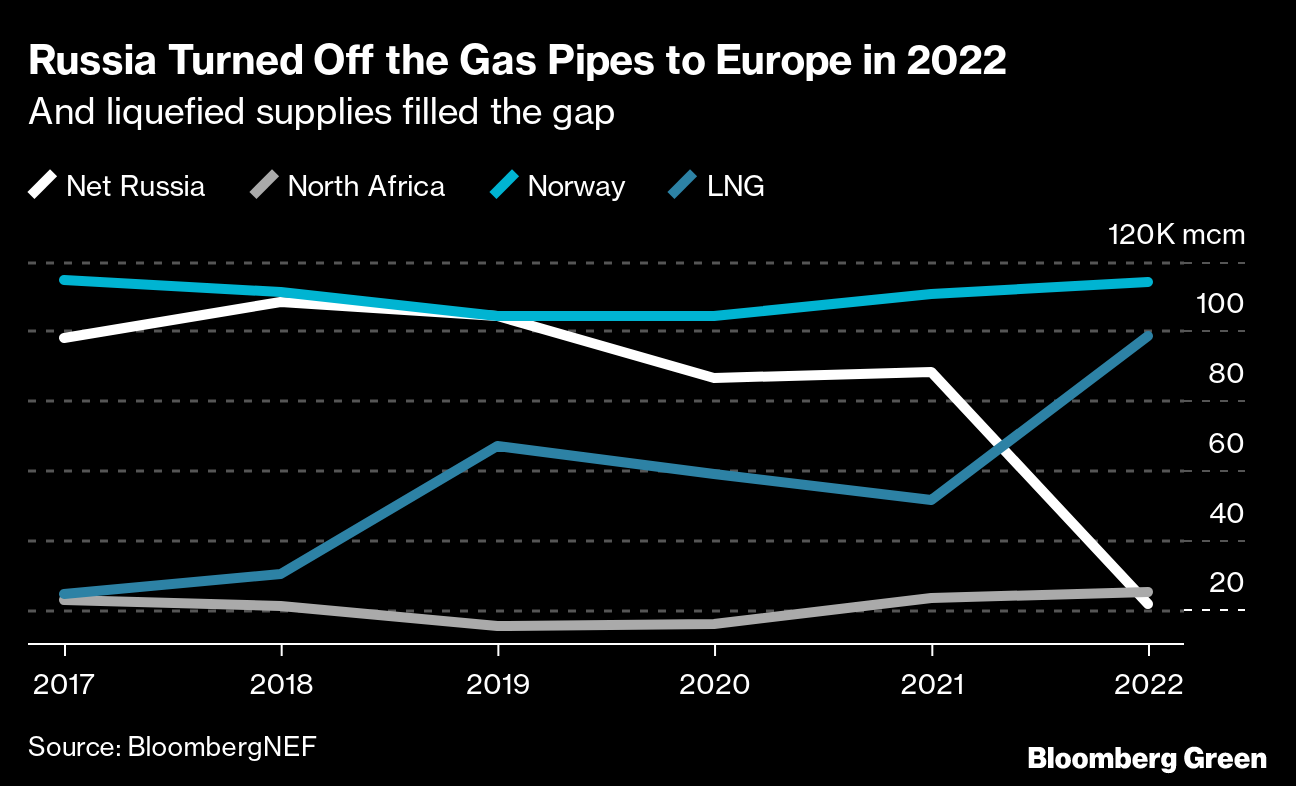

As Russian planes dropped bombs over Ukraine in July 2022, state-run Gazprom PJSC squeezed gas supplies through pipelines that went under the Baltic Sea or through Belarus and Ukraine. Initially, it was done under the pretense of maintenance complicated by Western sanctions. By summertime the Baltic Sea pipeline deliveries went nil after a series of explosions left them unusable.

By the end of 2022, Russian gas sent directly to Europe via pipelines fell 75% compared with the year before — and nearly two months into 2023, there’s no sign of imports increasing.

While ridding itself of cheap Russian gas, the EU’s gross domestic product actually grew 3.5% in 2022, just shy of the 4% expected before the war broke out. A recession was seen as inevitable as recently as the autumn, but EU economists now expect the bloc’s economy to grow by 0.9% in 2023.

“Almost one year after Russia launched its war of aggression against Ukraine, the EU economy is on a better footing than expected in autumn,” the European Commission said in its most recent economic report. “Inflation appears to have peaked and favorable developments in energy markets foreshadow further forceful declines.”

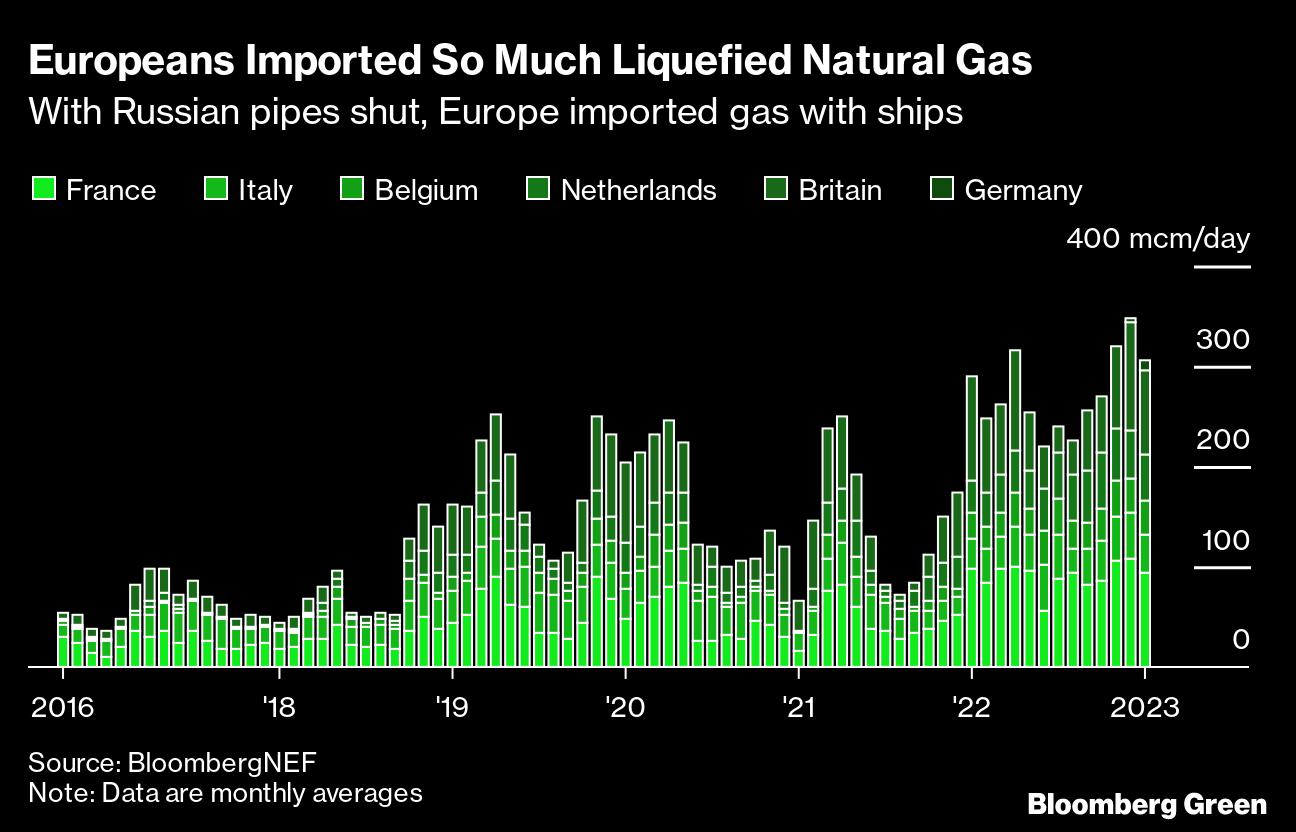

Some of the Russian gas was replaced by increased pipeline flows from Algeria and Norway. Most came on ships in the form of LNG, or liquefied natural gas. “Initially when the war kicked off it was very pessimistic and I didn’t know how the market would have coped without Russian gas,” said Arun Toora, analyst at BloombergNEF. “We made it through sucking every last drop of spot LNG.”

The Hoegh Esperanza LNG floating storage regasification unit, part of the Wilhelmshaven LNG Terminal, in Germany in December. Photographer: Liesa Johannssen/Bloomberg

The Hoegh Esperanza LNG floating storage regasification unit, part of the Wilhelmshaven LNG Terminal, in Germany in December. Photographer: Liesa Johannssen/Bloomberg

Securing all that gas meant buying up lots more from the US and Qatar, nearly doubling EU’s LNG imports compared to 2021. And ironically, Russia also served as an increasingly important source of liquefied gas, even as its piped exports to Europe dwindled. It helped that climate change meant a milder than average winter, which lowered heating demand. Warm temperatures have meant more gas in storage available for next winter.

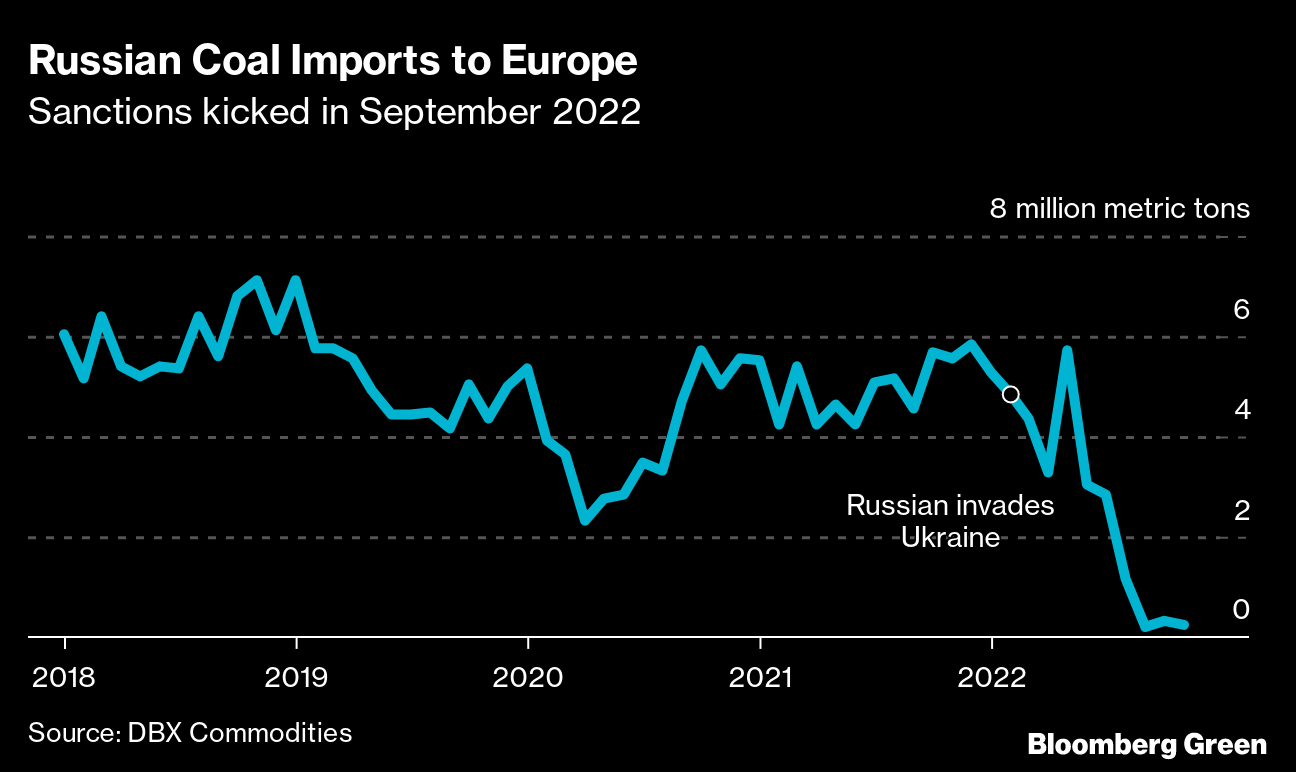

Some gas demand was reduced by burning more coal in power plants. Coal use across the European Union rose 7% last year, as Russian imports declined through the year and came almost to a complete halt in October after sanctions kicked in.

But the greatest help came in the form of reduction in demand from both industry and homes. As the price of gas shot up, some industries such as fertilizer producers found it uneconomical to operate, while others found alternatives to meet their energy needs. That led to an 18% decline in use over 2021, comparable to the 14% drop seen in 2020 compared with the year before. The story was similar for residential heating, which also fell 15%, according to data compiled by BloombergNEF from Europe’s biggest gas-consuming countries.

At the same time, sales of heat pumps rapidly increased across most European countries that have reported data—from Sweden to Poland. Early estimates suggest continent-wide sales may have increased 38% over 2021. Heat pumps are highly efficient, which means they require a lot less energy and thus are cheaper to run. “The idea of Russia as a reliable provider of energy is dead,” said Thomas Nowak, head of the European Heat Pump Association. “Now people are asking, ‘Am I the last person with a gas boiler?’”

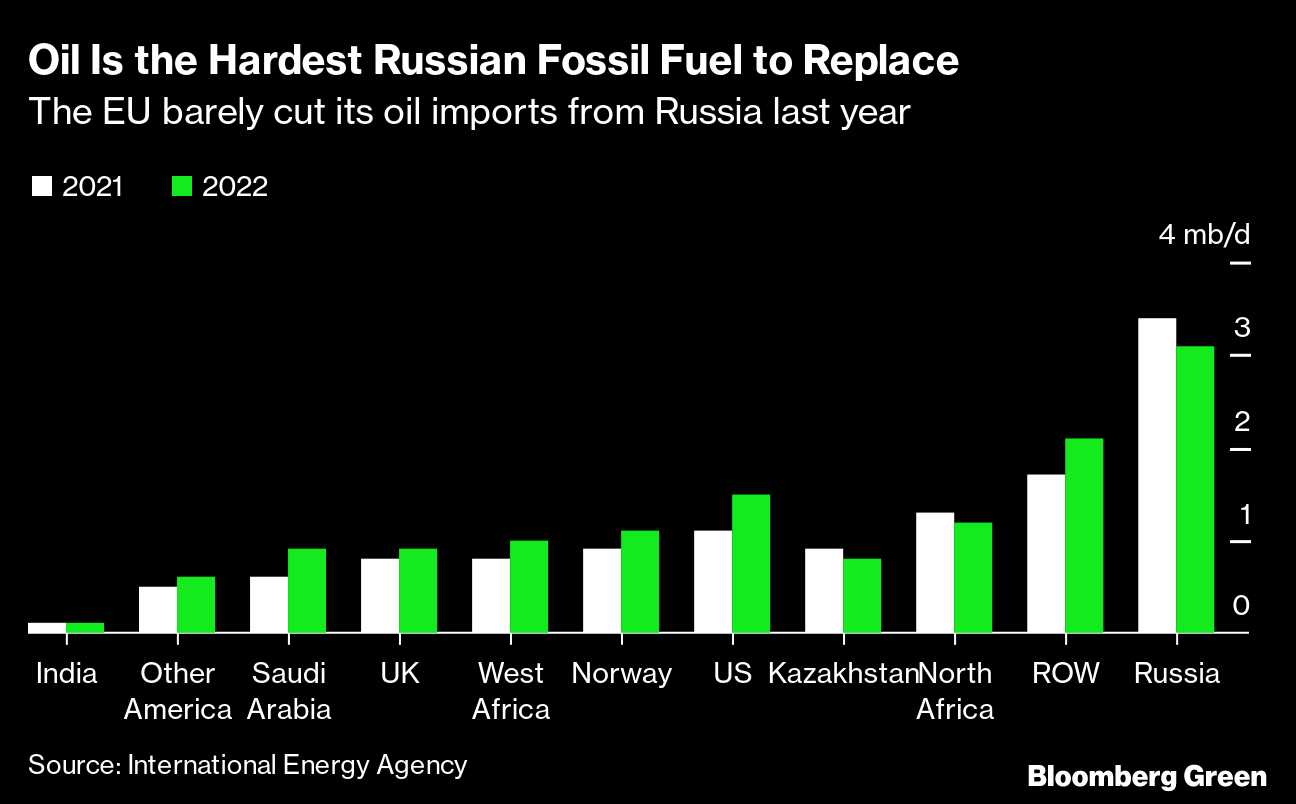

Oil imports also saw a decline in 2022, but not as much as coal or gas. Total imports from Russia fell by 300,000 barrels a day, which kept the country as the biggest exporter of oil to the EU, according to data from the International Energy Agency. Sanctions on crude imports applied since December and on refined productions such as diesel being put in place this month means that Russian oil imports should finally come to a halt a year later.

“Oil is harder to replace,” said Christof Ruhl, senior analyst at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and former chief economist at BP Plc. “It’s the most dangerous one to touch because if you have an increase in oil prices by 20% you risk a global recession.”

The Oiltanking Deutschland tank farm on the Teltow Canal in Berlin, Germany in December.Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bloomberg

The Oiltanking Deutschland tank farm on the Teltow Canal in Berlin, Germany in December.Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bloomberg

Imports from Russia have been replaced by increased shipments from the US, Saudi Arabia and Norway. The EU also worked with the Group of Seven countries and Australia to impose a price cap on Russian crude of $60 a barrel in December that is meant to allow Russian oil to flow around the world but deprive Putin of windfall profits if the market price soars.

And it’s worked, sort of. India has rapidly increased its import of Russian crude, which is being refined into diesel and gasoline in its refineries and often being shipped to Europe, where Indian imports of refined Russian crude are not on the sanctions list.

What Happens Next?

One of the biggest energy-transition headwinds that the EU has faced domestically over the past year was its worst drought in 500 years. Human-induced climate change made that drought at least 20 times more likely, according to a study published in October. The downstream impact on energy came through reduced hydropower output, which had previously been a reliable source of renewable energy.

An even bigger headache was France having to deal with its aging fleet of nuclear reactors. That effort stumbled in 2022, leaving Europe without one of its biggest sources of low-carbon power. Normally a power exporter, France was forced to import electricity from its neighbors last year, leading to even more demand for fossil fuels.

The Chinon Nuclear Power Plant on the Loire in France in September.Photographer: Nathan Laine/Bloomberg

The Chinon Nuclear Power Plant on the Loire in France in September.Photographer: Nathan Laine/Bloomberg

France’s nuclear fleet has been gradually returning to service this winter, although generation remains below historical averages. Still, stronger nuclear output and healthier hydro reservoir levels are set to help cut demand for gas and coal for power generation in 2023. Another win is Belgium and Germany extending the lives of their nuclear power plants that should further cut demand for gas, although the German extension is set to end later this year.

Despite all those changes, the EU’s greenhouse-gas emissions are set to decline by less than 1%. The increased emissions from burning coal, which produces twice as much carbon dioxide per unit of energy produced as gas does, were offset by the lower use of gas. Overall, electricity from fossil fuels is set to drop as much as 43% in 2023 compared with last year, according to BloombergNEF.

Acceleration away from fossil fuels is top of mind for EU lawmakers, who are so confident about meeting their 2030 emissions targets that they have already opened public consultation for 2040 targets on the way to net zero by 2050. The EU’s Green Deal is now firmly embedded in the bloc’s laws, including steps like banning the sale of fossil-fuel powered cars by 2035. That’s already starting to show in rising sales of electric vehicles with 2022 expected to set a new record.

The wartime energy transition has shown the EU what it can do to try to catch up to China’s lead on green technologies. Its green moves will accelerate as it responds to the US’s bold moves after passage of its biggest-ever climate bill last year that throws hundreds of billions of dollars in new subsidies at clean technologies. That sense of competition to get greener faster has many European lawmakers now hinting at more subsidies for deployment of green technologies across the bloc as well as leaner permitting processes and more manageable cross-border regulations.

“In Europe, we are seeing a further acceleration of decarbonization,” said Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency. “Russia is losing the energy battle.”

--With assistance from .

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GB Energy Faces New Doubts as UK Declines to Affirm Future Funds

Korea Cancels Planned Reactor After Impeaching Pro-Nuke Leader

Brazil’s Net-Zero Transition Will Cost $6 Trillion by 2050, BNEF Says

SolarEdge Climbs 40% as Revenue Beat Prompts Short Covering

EU to Set Aside Funds to Protect Undersea Cables from Sabotage

China Revamps Power Market Rules In Challenge to Renewables Boom

KKR increases stake in Enilive with additional €587.5 million investment

TotalEnergies and Air Liquide partner to develop green hydrogen projects in the Netherlands

Germany Set to Scale Down Climate Ambitions