China's Cutthroat EV Market Is Squeezing Out Smaller Players

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s largest electric vehicle market is putting its crowded infancy stage behind it.

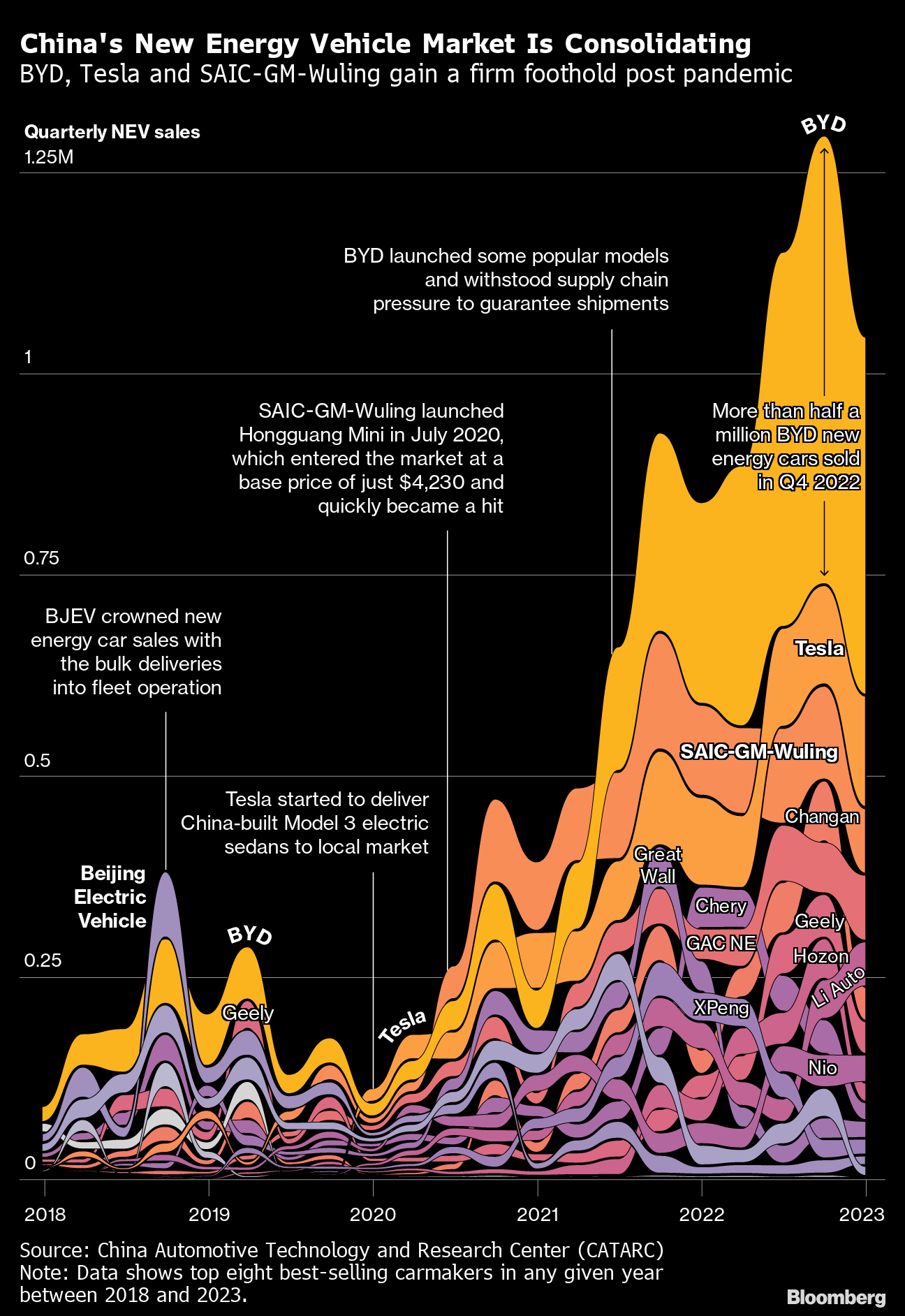

The explosive industry in China — supercharged by government subsidies more than a decade ago — now spans about a hundred manufacturers churning out pure-electric and plug-in hybrid models. While that’s down from roughly 500 registered EV makers in 2019, the end now looks to be in sight for scores more.

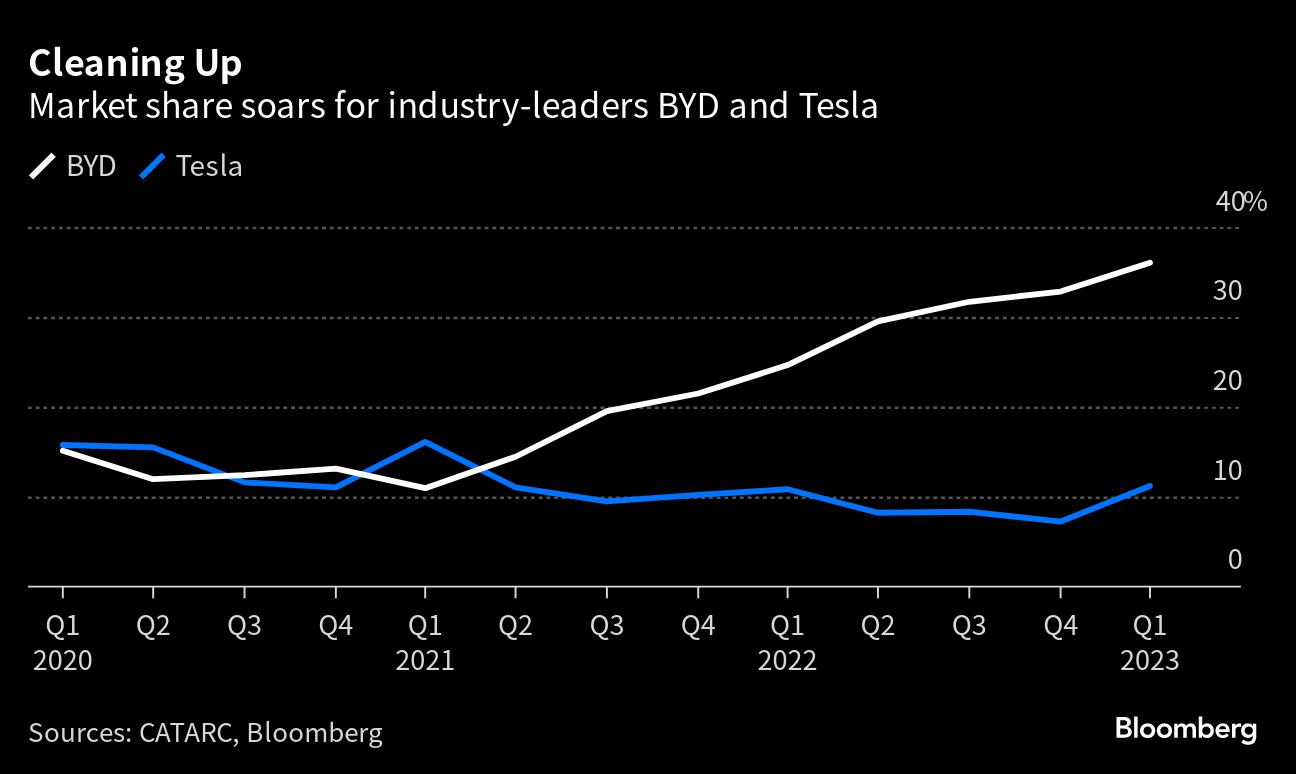

The cutthroat market formally transitioned from over-crowed to moderately concentrated in the first quarter, based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, a metric used by academics and regulators to evaluate competition and measure market concentration. The biggest winners are players already at the top, like BYD Co. and Tesla Inc., which have been consolidating their power.

According to Wang Hanyang, an auto analyst at Shanghai-based 86Research Ltd., “80% of the new energy vehicle startups, if we count all of them since the initial subsidies, have exited or are exiting the market.”

That’s not good news for struggling players like Nio Inc., whose sales have been tumbling and which said last week that the government of Abu Dhabi is taking a 7% stake following a capital infusion. Just two short years ago, Nio’s founder and CEO William Li was being mobbed by fans at customer gala dinners and the company was riding high after already escaping one near-death experience, fixed by a large financial injection from the municipal government of Hefei.

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index shows a clear consolidation trend over the past several years, winnowing the initial surge of new players that emerged when China first rolled out plans to support cleaner energy vehicles with state subsidies and other sweeteners.

The squeeze has only intensified over time, with dominant players strengthening their positions and smaller firms struggling to survive. The market share by unit sales for the top four players rose to 60% in the first quarter of 2023, compared to 44% the same period three years ago.

While China extended a tax break for consumers buying new energy vehicles through 2027, all signs are that the government won’t continue to prop up troubled carmakers. The consolidation push from market forces and regulatory mechanisms will help make the surviving brands internationally competitive, Xin Guobin, an official from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, said.

BYD, backed by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc., has witnessed its domination surge over the past two years. More than one-in-three NEVs sold in China today are from the Shenzhen-based company, up from less than 15% in late 2020 when the clean-car market first started steadily selling more than 100,000 units every month.

Its success is squeezing even the market’s No. 2 player, Tesla, which gradually lost share for the past two years until a breakthrough in the first quarter. Now it’s poised to grab about 11% of the pie, giving the two leaders nearly half of the market.

Meanwhile, some of the industry’s early crown jewels have silently disappeared. Many early electric vehicles were built mainly to qualify for subsidies and meet regulatory requirements, and often didn’t offer high-quality design and performance.

“We call them regulation cars,” said Jochen Siebert at JSC Automotive, a car consulting firm in Singapore, referring to the vehicles mostly sold to fleets and that were designed to meet fuel consumption rules and garner new-energy credits and other subsidies. “The only important thing was that they had to be an EV.”

Demand for those vehicles started to fade once requirements increased, competitors emerged and the fleet market became saturated.

Zhidou Electric Vehicles Co., a Ninghai-based manufacturer once backed by Li Shufu’s Zhejiang Geely Holding Group, sold a total of about 100,000 vehicles with a driving range of as little as 62 miles (100 kilometers) per charge between 2015 and 2017. The micro-car maker quickly lost momentum after China ended subsidies for EVs that traveled less than 93 miles between charges in 2018.

Similarly, Beijing Electric Vehicle Co., the EV arm of state-owned BAIC Motor Corp. that led sales of pure-electric cars for more than five years by targeting mainly fleet operators, started to report losses after the subsidy slide. It subsequently changed its strategy.

Byton Ltd., founded by former managers of BMW AG, had to suspend production before delivering its first car, while Zhiche Youxing Technology Shanghai Co. — which initially planned to list on China’s Star Board in 2019 — was nearing bankruptcy in 2022.

But the market is by no means easy for carmakers trying to lure customers rather than meet regulatory rules.

One of the most recent corporate casualties in the slow-motion shakeout was WM Motor Technology Group Co., the Shanghai-based electric-car maker backed by tech giant Baidu Inc.

About a month and a half after the company announced in January it would use a reverse merger to go public in Hong Kong, reports emerged that it was cutting pay and conducting lay-offs. Sales have plunged.

Freya Cui, a resident of Shijiazhuang in northern China and one of the earliest owners of WM Motor’s EX5 sports utility vehicle, had to walk away from her four-year-old car in April due to a battery pack defect.

The dealer told her no replacements were available because of the company’s financial troubles, and hers wasn’t the only case. It would cost even more than the vehicle’s initial post-subsidy price to buy a new battery pack from a third party, she said.

After several failed attempts to reach WM Motor or its chief executive Freeman Shen on social media, Cui bought a cheap gasoline car for commuting purposes, while holding out hope for the company’s recovery.

“I placed the order even before seeing an actual car, and the life warranty of battery pack was a huge plus to me,” said Cui. “Who would have thought the company would one day be on the brink of collapse?”

WM’s reversal of fortune is stark. The once-highly lauded company landed two of the top five venture capital investments by deal size in the clean car market in China since 2018, according to capital market data provider Preqin. Investors in the transactions — which took place in 2020 and 2021 — ranged from leading state-owned banks to tech firms.

Whether the pace of market consolidation will continue amid still nascent consumer interest in electric cars is difficult to say. New-energy vehicle retail sales jumped to 580,000 units in China last month, but accounted for only one-third of the total deliveries of passenger cars, data from the Passenger Car Association show.

Siebert expects the cool features like autonomous driving functions, large built-in screens and even karaoke systems found in the initial wave of EVs to give way to a focus on safety, performance and durability, a shift that may offer legacy automakers like Volkswagen AG an advantage.

“The next five years will be decisive,” he said.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

Key Permit for New Jersey Wind Farm Trump Opposes Is Voided

Danish Investor Raises €12 Billion for Renewable Energy Fund

What It Will Take for Rich Countries to Reach Net Zero: You

Bill Gates’ Climate Group Lays Off US and Europe Policy Teams

Trump’s EPA Takes Aim at Biden Curbs on Power Plant Pollution

Deals Seeking $45 Billion in Climate Funds Seen Managing US Exit

TotalEnergies and RWE join forces on green hydrogen to decarbonise the Leuna refinery

Shale Pioneer Sheffield Warns Oil Chiefs of Grim Times Ahead

Investors Learn Brutal Lesson From Sweden’s Wind Farm Woes