Free Green Power in Sweden Is Crippling Its Wind Industry

(Bloomberg) -- Sweden’s wind power industry risks becoming a victim of its own success.

The country has one of the greenest grids in the world, relying almost entirely on hydroelectric, nuclear and wind, which now generates about a quarter of its supplies. But even more is needed to electrify the rest of its economy.

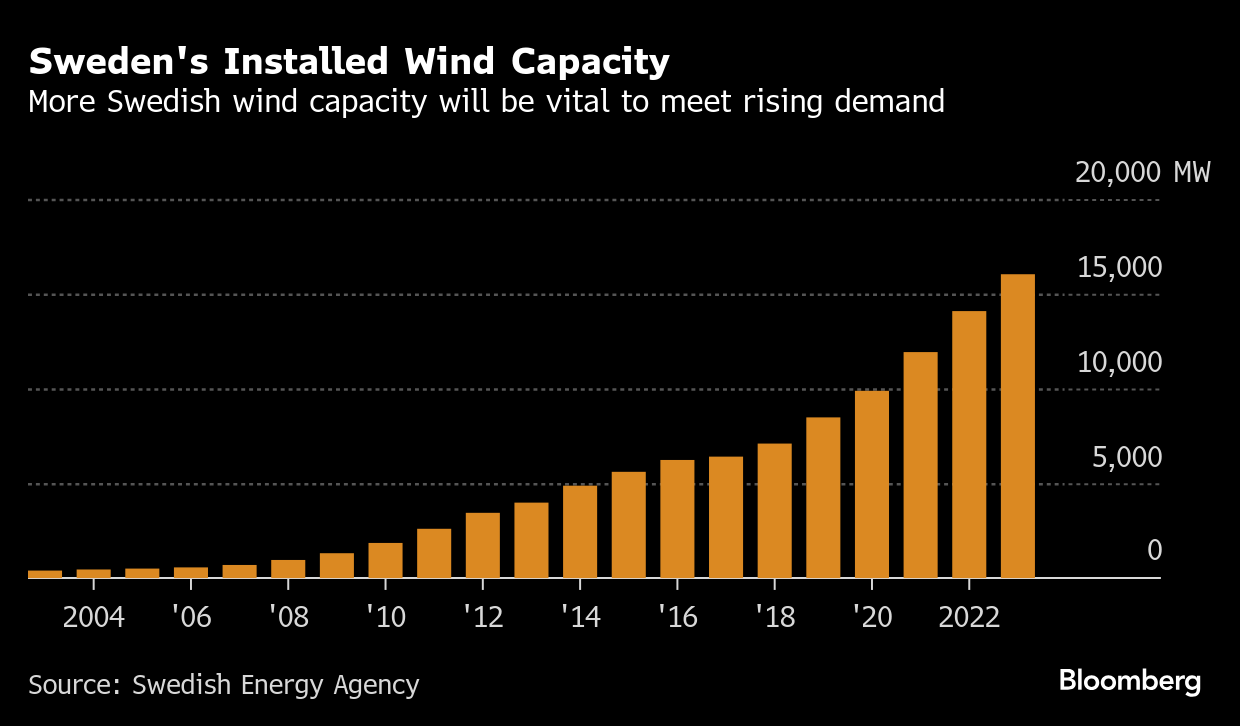

The expansion of thousands of wind turbines in Sweden over the past two decades means there’s so much power around that electricity prices are increasingly dipping below zero, both for whole days and individual hours, and are expected to remain very low for years.

The market turmoil is discouraging investors from backing new renewable developments in the country as rock-bottom power prices offer little return. Doubts are also growing over what demand will be in the future as a number of energy-hungry green industrial mega-projects in the north get delayed or canceled altogether. A Danish auction for new offshore wind farms failed to attract any bidders in another sign of stress for green investment.

Sweden, which ended its main subsidy system for new renewable projects three years ago, is offering a glimpse into a world where investments in clean power are driven by the price of energy alone. That makes it stand out in Europe, where nations from the UK to France and Germany still offer a variety of incentives.

Plunging prices aside, Sweden’s wind industry already faces obstacles — from higher turbine costs and interest rates to not-in-my-back-yard opposition, municipal and military vetoes as well as elusive grid connections.

“It’s certainly a challenging situation,” said Matilda Afzelius, chief executive officer for the Nordic region at Renewable Energy Systems Holdings Ltd., which develops green power projects in more than 20 countries around the world. “We’re definitely facing headwinds, everything is much slower than we’d like and expected.”

The lull is threatening Sweden’s ambitious goal of reaching net zero emissions in 2045, earlier than the European Union’s midcentury target. And it’s not just Sweden: A global goal to triple renewable energy capacity by the end of the decade is in danger because the rollout of wind turbines is too slow, according to the International Energy Agency.

No new turbines have been ordered in Sweden since the first quarter, according to the latest data from industry group Svensk Vindenergi, the longest such stretch in two years. It now takes as long as 8.5 years to bring a wind park in Sweden from application to operation, up from 2.5 years in 2010, according to consultant Ernst & Young. This extended timeline creates significant challenges for developers and investors, especially in a market where demand for renewable energy is growing rapidly.

As the nation’s green-tech revolution wobbles, estimates for how much demand will grow vary widely among analysts, but the government expects it to double in the next two decades. One thing is clear: More wind capacity will be vital to meeting the surge.

BloombergNEF sees annual onshore wind-power additions at 400 megawatts from 2030 to 2035, down from 2,604 megawatts last year. Sweden’s installed wind capacity is the fourth largest in the EU, totaling about 16,400 megawatts at the end of 2023.

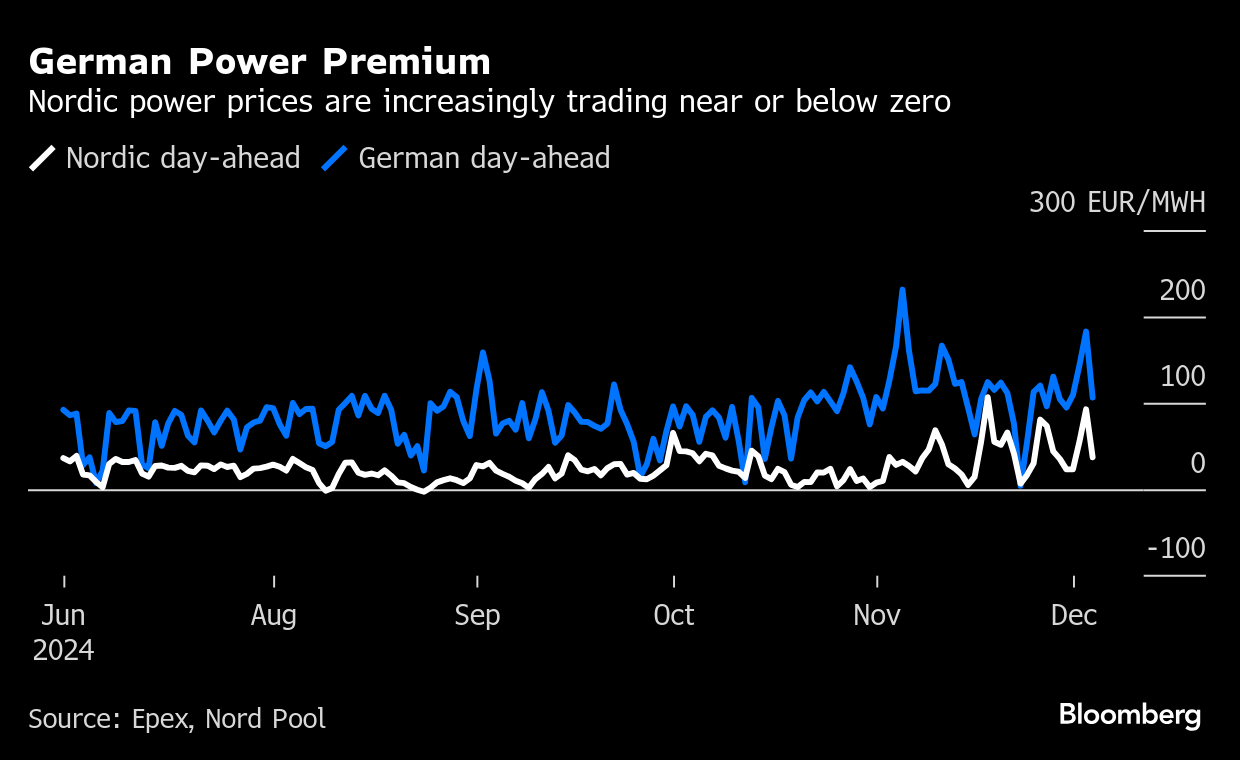

Other countries still trying to decarbonize with the help of subsidies rely more on fossil fuels, which translate into higher electricity prices. For example, the average Nordic rate this year is about €36 ($37.90) a megawatt-hour, or half of Germany’s, which is Europe’s biggest market.

“The price gap could widen further if demand stagnates,” said Sigbjorn Seland, chief analyst at StormGeo AS in Oslo, who’s tracked the market for more than two decades. “Prices could be close to zero for extended periods” in parts of the Nordic market from 2025 to 2027, he said.

While utilities, asset managers and funds that buy wind parks invest on a much longer horizon than that, it’s still a worrying sign.

“Investors are naturally quite nervous looking at what happened in the Nordics, thinking, could it happen elsewhere?” said Yinfan Zhang, a director at industry consultant Baringa Partners. “One example could be Spain, where we have a lot of solar development and power prices are being pushed quite low.”

In the first half of this year, 12 of 16 new wind projects in Sweden were shot down by local municipalities using veto power, with three of the remaining four halted by the military, data from Svensk Vindenergi show.

“From a permitting perspective, it’s the most challenging time since I started in the business more than 25 years ago,” said RES’s Afzelius. “Applications are just not getting through.”

As a result, RES, as well as other developers in Sweden, are diversifying more into technologies beyond wind, including solar, batteries and hydrogen. RES just sold a green aviation fuel project in Sweden to German asset manager Prime Capital AG. “Things take so long in the wind power business. We need to get a quicker turnaround on our capital,” she said.

Some countries that have faced onshore wind project opposition have turned their eyes to the sea. Surprisingly, Sweden has almost no offshore wind capacity despite having the longest coastline of all the Baltic countries.

Last month, the government dropped a bombshell when it canceled 13 applications for projects in the Baltic Sea, saying they would harm the nation’s defense against Russia. That has forced utilities including wind giant Orsted A/S to reevaluate their Swedish activities. Germany’s RWE AG and even global furniture retailer Ikea had also been planning to back offshore wind projects in Sweden’s Baltic waters.

“We were quite convinced that we could find solutions to serve the needs of the armed forces and also the government because we have several experiences in other Baltic Sea countries such as Germany, Poland and Denmark of collaborating with the military and finding mutually beneficial solutions,” Orsted CEO Mads Nipper told reporters on a call.

A further worry for the wind industry is the government’s bullish plans for new nuclear. Proposals include a 40-year contract-for-difference price at the equivalent of €70 per megawatt-hour for the output. Even the best wind projects would struggle to compete with that.

For new reactors, the financial incentive to produce would be very high regardless of the market price, said Andreas Ivert, a senior manager for corporate finance at EY.

“The result could be lower energy prices, more frequent negative prices, and a market environment where wind and solar might struggle to compete with subsidized nuclear generation,” he said.

(Updates with Danish example in the fourth paragraph)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

New Jersey Wildfire Is Tied to Arson as Firefighters Make Gains

US Green Steel Startup Raises $129 Million Amid Trump Tariff Uncertainty

Musk Foundation-Backed XPRIZE Awards $100 Million for Carbon Removal

Nissan Commits Another $1.4 Billion to China With EVs in Focus

NextEra Energy reports 9% rise in adjusted earnings for Q1 2025 as solar and storage backlog grows

US Imposes Tariffs Up to 3,521% on Asian Solar Imports

India Battery-Swapping Boom Hinges on Deliveries and Rickshaws

China Reining In Smart Driving Tech Weeks After Fatal Crash

Japan Embraces Lab-Made Fuels Despite Costs, Climate Concerns