Altman’s $3.7 Billion Fusion Startup Leaves Scientists Puzzled

(Bloomberg) -- Sam Altman, the billionaire chief executive officer of OpenAI, is staking a sizable chunk of his personal wealth on a startup chasing the holy grail of nuclear fusion – the elusive, theoretically limitless clean-energy source that, he says, is key to an artificial intelligence-enabled future.

While other billionaires, including Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and George Soros, have backed fusion ventures, Altman has made his largest personal investment in Helion Energy, which stands out for its audacious timeline. It plans to open the world’s first fusion power plant by 2028 and to supply Microsoft Corp. with energy from it soon after.

That’s tantamount to the blink of an eye for an industry that’s been trying to produce fusion energy for the better part of a century. Even given recent scientific breakthroughs, Helion’s goal is still several years ahead of what the technology’s biggest boosters call feasible.

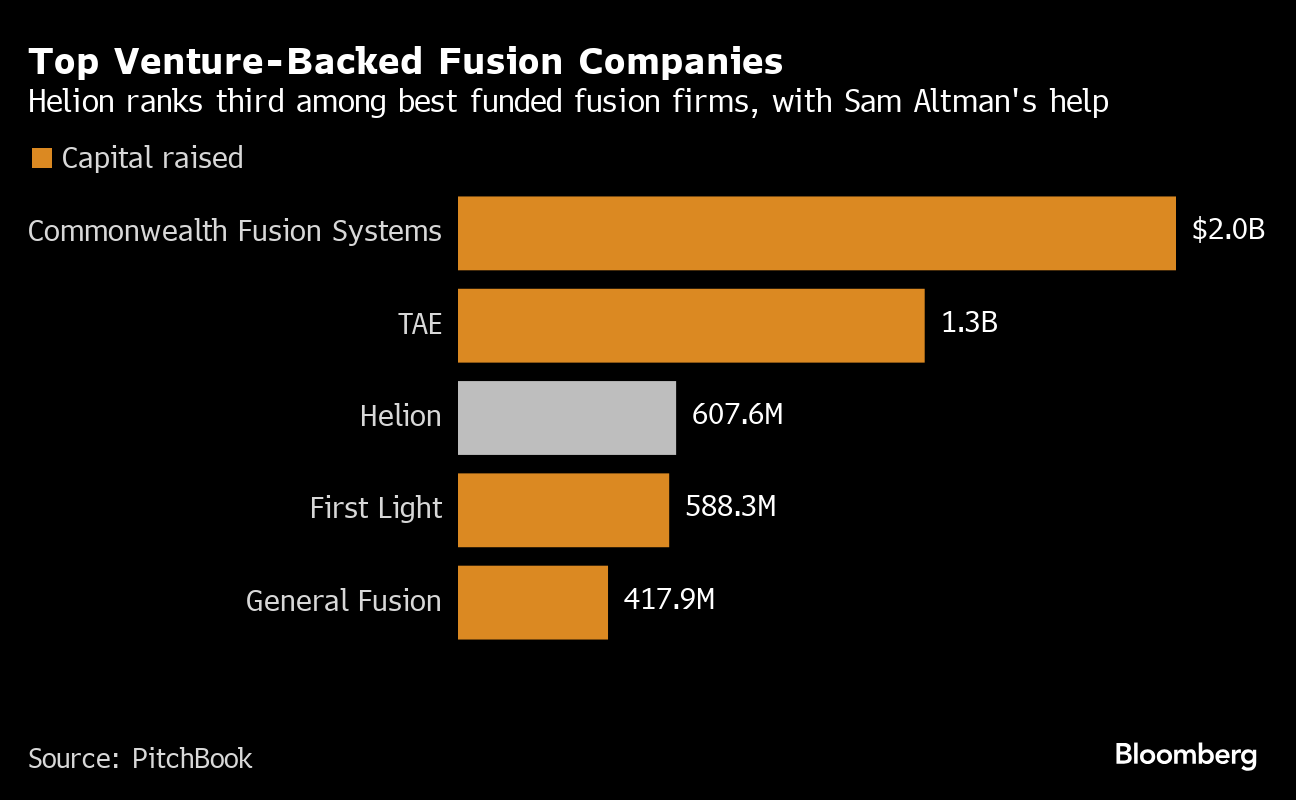

Helion offers little to persuade doubters or skeptics. Though it’s among the best-funded fusion companies, it doesn’t publish experimental results or engage in peer review the way large rival startups do, raising red flags in the scientific community.

CEO David Kirtley says the main task isn’t necessarily publishing — it’s building a fusion reactor.

“When we founded Helion, our goal wasn’t to demonstrate interesting new physics,” Kirtley said in a March interview. “By iterating and building quickly, you actually learn more than you ever could if you did a lot of simulation and a lot of computation upfront.”

But at the company’s headquarters in Everett, Washington, workers have their own reservations. In text messages and other communications reviewed by Bloomberg News and in interviews, current and former Helion employees expressed frustration with the company’s progress and skepticism that its seventh fusion prototype, named Polaris, will be operating to satisfy its internal year-end deadline.

Complicating the aggressive timeline, Helion is reckoning with a series of complaints of harassment and gender discrimination. At least five women have sought redress in the past two years, including a scientist who departed following an investigation of harassment, writing in a note to coworkers she would seek an employer “more aligned with my values and ideals.” (Through a spokesperson, Kirtley said Helion is “focused on creating a diverse and inclusive workplace.”)

Altman has been involved with Helion for about a decade. He was leading Y Combinator in 2014 when the startup’s founders joined the incubator. And his support continued: In 2021, Altman invested $375 million, according to CNBC, part of a $500 million fundraising round that included Peter Thiel’s Mithril Capital and Meta Platforms Inc. co-founder Dustin Moskovitz.

“I am confident in the research,” Altman, the venture's chairman, said in a statement. “I really believe in the company and their technology.” Both he and Helion declined to comment on the size of his stake in the company, which now has a total value of $3.7 billion, according to PitchBook.

He’s made no secret of his interest in clean energy. He’s invested in and sits as chairman of Oklo Inc., a different kind of nuclear power startup, which went public through an Altman-backed blank check company this year. His technology bets have helped make him a billionaire, but his overlapping investments and primary enterprise, OpenAI — which briefly banished him from leadership last year — also raised questions about his oversight, as well as the climate impacts of a future built on such an energy-intensive technology. Helion’s fate could speak to both.

Kirtley, 45, is the affable face of Helion. He co-founded the company in 2013 with John Slough, Chris Pihl and George Votroubek. “We all shared this vision of how to build products quickly,” Kirtley said.

In focusing on fusion, they dove into a scientific morass. Unlike fission – the process of splitting atoms that underpins nuclear energy plants – fusion attempts to create energy by smashing atoms together. That requires extreme temperatures, gigantic machinery and tons of power but, hypothetically, could produce more energy than it requires, a feat of physics and engineering that no one’s pulled off in any sustained or practical way.

Despite decades of slow progress, scientists haven’t given up. Fusion, in theory, would be a nearly perfect source of energy. It’s not extractive, like fossil fuels. It doesn’t emit greenhouse gasses or create mountains of radioactive waste. Until recently, researchers remained almost entirely at the mercy of government funding.

Advances in technology, a critical scientific breakthrough and growing demands for clean energy persuaded billionaire funders that fusion is more than a pipe dream. The fusion industry has attracted more than $7 billion in investment, according to a 2024 Fusion Industry Association report, which said the fundraising reflected “growing confidence in fusion technology’s potential to revolutionize the global energy landscape on a timescale that is relevant to investors.”

The lion’s share has accrued to the Gates- and Soros-backed Commonwealth Fusion Systems, spun out from MIT, and to TAE Technologies. Combined, those two have raised $3.3 billion, but the field counts more than 40 commercial ventures around the world, each with its own ideas for how to create, sustain and harness a fusion reaction.

For much of its first decade, Helion ran lean, using government funding and building six prototypes. With the influx of capital in 2021, Helion quickly quadrupled its workforce to more than 300. Less than a quarter are trained researchers; roughly half are machinists, building and assembling parts of Polaris.

The workforce makeup may reflect Helion’s determination to plow forward and build, without necessarily participating in the public processes that typically demonstrate scientific progress or reassure investors.

“They are basically saying, ‘We are going to skip some steps. We’re just going to build the machine,’” said David Ruzic, professor of nuclear, plasma and radiological engineering at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Helion’s deal with Microsoft – to provide electricity from a fusion power plant built by 2028 – caught some staffers by surprise, according to interviews with former employees who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. They also expressed doubts about the company’s promise to get the Polaris prototype running by year-end. “It doesn’t sound feasible,” one employee wrote in a message to colleagues. Another replied, saying that in private conversations, even Kirtley didn’t sound certain.

A Microsoft spokesperson said the company is “optimistic about this technology and its potential to benefit the planet.”

The imminent goal for Helion is to complete Polaris by Oct. 14 so it can begin testing. “There is a lot of risk in that date,” a senior Helion engineering employee acknowledged in an internal publication reviewed by Bloomberg News. As an incentive, the company promised every team member a $50,000 cash bonus and $50,000 of Helion stock options if it meets the target.

Internal reservations haven’t slowed Helion’s appeals to potential customers. Four months after Helion announced its deal with Microsoft, Nucor Corp., the largest steel manufacturer in North America, invested $35 million and agreed to collaborate with Helion to build a 500 megawatt fusion power plant. Helion announced a stock buyback days later, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Helion has also been in talks with Altman’s OpenAI to provide “vast quantities of electricity” to power data centers, the Wall Street Journalreported in June.

Many scientists reacted with disbelief and concern about the consequences of a high-profile failure to deliver. “I have a problem with them making promises that might not be kept,” said Saskia Mordijck, a plasma physics professor at William & Mary. “That is damaging to the whole fusion community.”

In June, Commonwealth CEO Bob Mumgaard issued a public call for fusion companies to back up their claims with peer review – a rigorous fact-check before results are published in a journal, and a mark of credibility.

“The industry must not give into marketing hype,” Mumgaard wrote. “Press releases without proof will do more harm than good to stakeholders’ trust in fusion.”

Every company working on cutting-edge technology tries to protect its intellectual property. Still, other fusion startups have found ways to make public some of their experimental results. Sharing concrete evidence, including about the heat and stability of their plasma — where fusion reactions happen — is necessary to build credibility within the industry, with investors and ultimately in the market, Mumgaard wrote.

Helion has several patents and published a modeling paper in 2023, but it did not include experimental data.

Helion has also been relatively scarce at certain high-profile conferences, where business leaders and academics gather to share their work, check up on the competition, and recruit. The most recent annual meeting of the American Physical Society Division of Plasma Physics featured dozens of abstracts from other well-funded companies including Commonwealth, TAE and Zap Energy Inc. Helion submitted two.

Former employees say management has refused some requests to participate in industry events and rebuffed questions about why the company trumpets its achievements, like heating up plasma to 100 million C, without publishing peer-reviewed research. Several described Kirtley as fanatical about secrecy and worried about idea-snatching, floating the specter of corporate espionage in internal meetings. He raised similar concerns before Congress, invoking a machine being built in China “that looks just like schematics released by Helion in 2014.”

The company is more open with less technical audiences. Last year, the company hosted science vlogger Jason Bowles for a visit; the video shows the inside of Helion’s facility, which Bowles likens to “Iron Man’s basement.” It declined requests for a tour from Bloomberg News.

Altman is Helion’s most visible advocate, touting the company on X, podcasts, mainstream media and on his blog. A press release quotes Altman calling Helion’s ideas “

The PR push has also landed badly with some employees. At one point, Helion approached Grace Stanke, a nuclear engineer and Miss America 2023, about a role to promote the company and its technology. At the time, workers questioned the firm’s pursuit of a high-profile advocate when it had yet to hire a professional in charge of general floor safety, according to people familiar with the matter.

Ultimately Stanke never worked with Helion. “I don’t think it was the right fit,” she said.

Worker Morale

With the deadline for Polaris approaching, Helion faces another obstacle to worker morale: complaints of discrimination and harassment in the workforce.

At least twice in the past two years, female ex-employees pursued legal action against Helion over issues that included wrongful termination, workplace discrimination and pay, according to people familiar with the matter. Kirtley said in an emailed statement that, in the same time frame, the firm had created an annual pay equity analysis and took other measures, including “iterating on our compensation philosophy to increase transparency.”

Last year, Claire Saunders, a materials science PhD and one of Helion’s celebrated hires, reported harassment by her male manager, according to people familiar with the allegations — including comments about forcibly inserting material into a neutron generator, referred to in the feminine. Saunders and her manager were placed on leave while Helion investigated, but it yielded “insufficient evidence of discrimination,” according to a message to staff viewed by Bloomberg News. A Helion spokesperson said a third party “

Saunders left in November, writing in a message to colleagues that she’d faced “challenges that have made it important to seek a setting more aligned with my values and ideals,” according to a copy of her note viewed by Bloomberg.

Reached by phone, Saunders declined to comment on her departure.

“We’re committed to continuously improving our environment,” Kirtley said in a statement.

Quicktake: The Nuclear Fusion Energy Breakthrough, Explained

Over Zoom in March, Kirtley had just 15 minutes before a design review. Fusion scientists may be uniquely predisposed to tune out critics and naysayers, but not to the exclusion of healthy skepticism, Kirtley said.

“As an engineer and as a scientist, I enter into every situation looking for what could go wrong and what’s not going to work so that we can solve that problem,” he said. “We’re problem solvers by nature.”

The financial incentives are persuasive. As part of the company’s latest round of fundraising, Helion could get an additional $1.7 billion if it reaches performance milestones.

“Right now the focus is: How do we build, and ideally on how do we move as fast as possible to get Polaris up and running,” Kirtley said. “All of those final parts to get assembled, and put it in the machine to turn it on. That’s been our focus.”

(Updates to add information from the Fusion Industry Association report. An earlier version corrected the heat of fusion fuel.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.