US Nuclear Industry Fetes Rare New Reactors as Retrofits to Dominate

(Bloomberg) -- The US nuclear industry threw a huge party in Georgia to celebrate the country’s first new reactors in more than 30 years.

Fanfare last week over the long-delayed expansion included a choir, color guard and a big yellow cake shaped like the Alvin W. Vogtle facility. Governor Brian Kemp even quipped to a crowd of hundreds about building another reactor there.

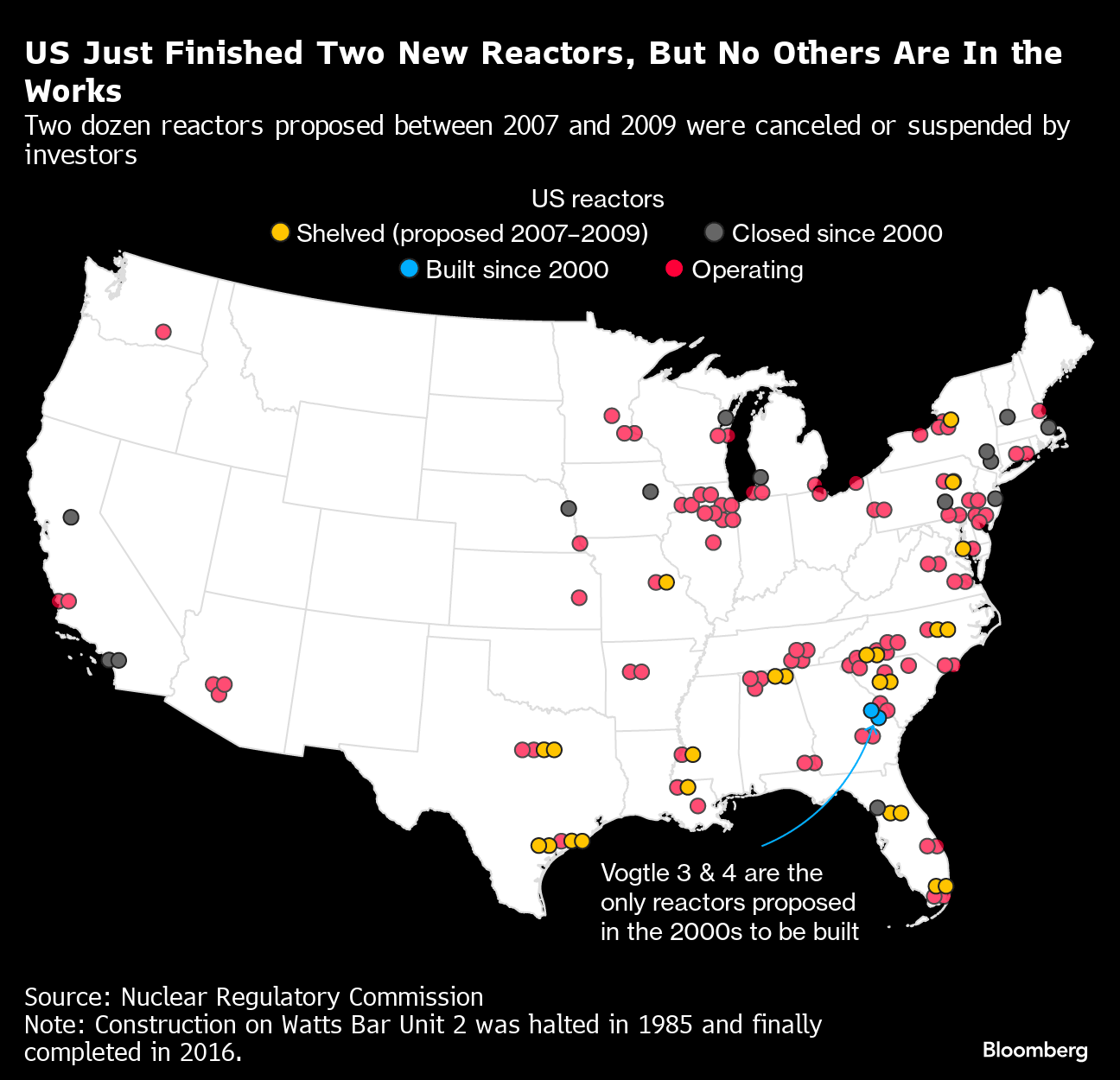

But the festivities mask a difficult truth: while Vogtle marks the country’s biggest nuclear advance this generation, it will be the last reactor built for a long time. The project’s delays and ballooning costs have cooled enthusiasm for new reactors, despite resurgent interest in nuclear power. Instead, the country is set to do something more prosaic — retrofit existing plants.

When it comes to building new capacity, “I’m telling utilities in other states: ‘Don’t pursue this path without some protection from overruns,’” Tim Echols, vice-chairman of the Georgia Public Service Commission and Vogtle champion, said in an interview at the May 29 bash. “It’s still too risky.”

Echols speaks from experience. Southern Co.’s effort to build two more reactors at its facility 175 miles (280 kilometers) east of Atlanta came in seven years behind schedule and more than double its $14-billion budget, with recent outside estimates above $35 billion.

Big reactors like Vogtle can take a decade or more to build, and none are on the drawing board in the US. The nuclear industry is still hopeful about the next generation of fission technology — small modular reactors that can be produced in a factory and assembled on site — but a series of setbacks mean few are likely to be in service before the end of the decade. At this point, wringing a modest amount of power from aging plants is the only way to capitalize on renewed interest in nuclear power.

“It’s impossible to build a new reactor,” said Chris Gadomski, lead nuclear analyst at BloombergNEF. “You might as well upgrade the ones you have.”

It’s a stark contrast from China, which is on track to surpass the US and become the biggest nuclear-powered nation by the end of the decade. The Asian country may add as many as four reactors in 2024, and could soon be approving as many as 10 a year.

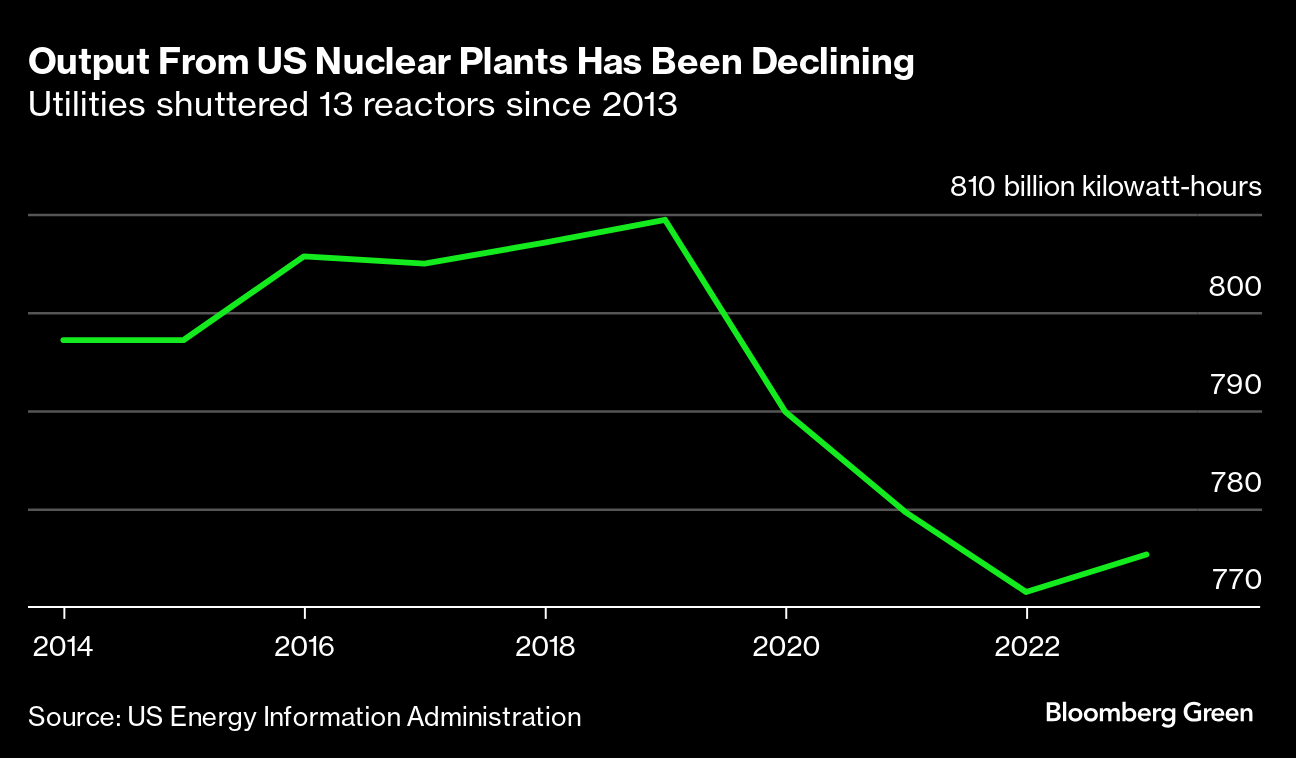

Just three years ago, the US nuclear industry was practically left for dead. Reactors are costly to operate and owners struggled to compete against cheaper power from natural gas and renewables. But the growing climate crisis is now driving up demand for clean energy, helping spur interest in carbon-free fission power. A surge in anticipated electrical demand — thanks to artificial intelligence, data centers, new factories and electric vehicles — has also sparked enthusiasm for reactors.

Southern’s Vogtle experience leaves the door open to a more palatable option for operators — expanding output with upgrades. The approach has limits and certainly won’t generate enough power to address America’s growing electricity demand.

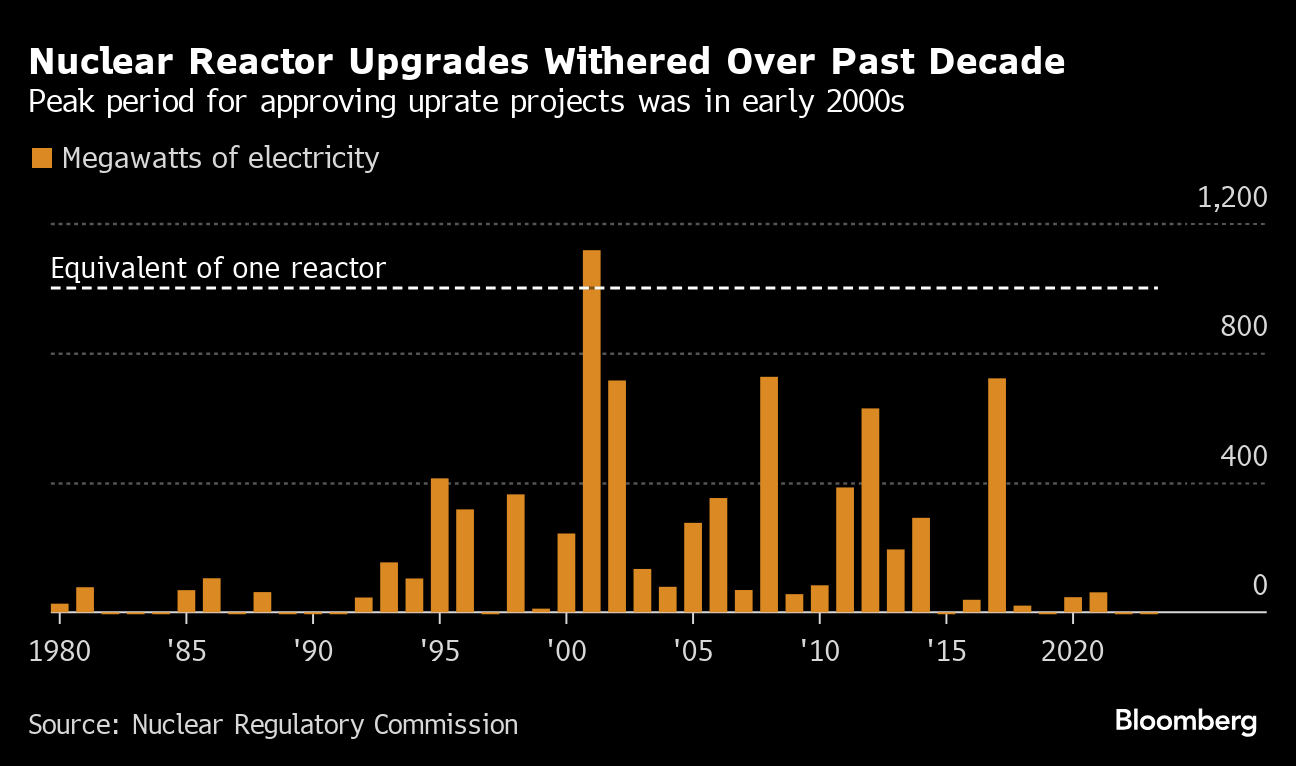

The Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group, expects upgrades will add about 2.5 gigawatts of capacity to US grids by 2032 — a little more output than Vogtle’s two new units — in what’s known in the industry as “uprating.” While this isn’t a new idea, operators pursued few of these projects in a decade-long industry slump that saw more than a dozen reactors shuttered.

A change in political will is giving a boost, with the White House throwing its weight behind building reactors to help mitigate industry risk associated with costly construction projects. President Joe Biden’s signature 2022 climate law also offers tax incentives that have made utilities reconsider the economics of investing in nuclear.

“The new tax incentives open the door,” said Doug True, chief nuclear officer at the Nuclear Energy Institute. “We could see a pretty good batch of uprates coming.”

There are three main strategies for uprating a reactor’s capacity. The easiest involves installing more precise tools for tracking plant operations, allowing the utility to run systems at slightly higher rates while staying within safety parameters. This can lift output by about 2%. Operators can also install new equipment, which can increase output by as much as 7%, or pursue a more involved overhaul that can boost capacity by as much as 20%.

All need approval from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The government agency authorized more than 170 such projects from 1977 through last year, adding about 8 gigawatts of nuclear power. Still, only 18 of those were approved in the past decade, with most involving better measuring tools. The commission hasn’t received any applications in the past two years.

Among past approvals, Duke Energy Corp. is adding better measurement systems at its Oconee plant in South Carolina to boost capacity to the site’s three reactors this year, delivering enough extra power for 30,000 homes. Meanwhile, Energy Northwest is evaluating a capacity expansion at its Columbia plant, which supplies about 10% of Washington State’s electricity, and expects to submit a proposal to the NRC in 2028.

Constellation Energy Corp., the biggest US nuclear operator, is spending $800 million to replace the main turbines at its Byron and Braidwood plants in Illinois. The company expects 1 gigawatt of upgrades across its entire nuclear fleet within a decade, Chief Generation Officer Bryan Hanson said. He anticipates others will pursue upgrades.

“Every nuclear operator, if they haven’t done it already, is considering it,” Hanson said.

Still, industry interest in building reactors hasn’t completely disappeared.

“A lot of people are asking us for our lessons learned,” Kim Greene, head of Southern’s Georgia Power unit, said in an interview at Vogtle’s fete. “I do hope they’ll follow suit.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

Trump Halts NY Offshore Wind Project Work Amid Sector Review

Big Bets on Speculative Carbon Capture Tech Ignore Today’s Solutions

UK Grid Warns Record Low Power Use to Test Network This Summer

AI to Prop Up Fossil Fuels and Slow Emissions Decline, BNEF Says

UK Approves Grid-Queue Overhaul in Race to Clean Up Power System

Europe’s Hottest Year Turbocharged Extreme Weather Across Region

Khosla-Backed Energy Startup Nabs $258 Million to Help Power Data Centers

Peter Thiel Joins Board of Enriched Uranium Startup General Matter

Plan to Green 30,000 Africa Buildings Seeks $150 Million Boost