Silicon Valley’s Elite Pour Money Into Blotting Out the Sun

(Bloomberg) -- When back-to-back hurricanes made landfall in Florida this fall, conspiracy theories followed. Among the unfounded claims circulating on social media was the idea that the US government had effective control of the weather, spinning up storms to strike areas based on political affiliation. While that’s not true, there are people working in semi-secret on technology to tweak the weather, even if they’re nowhere close to controlling hurricanes.

A growing number of Silicon Valley founders and investors are backing research into blocking the sun by spraying reflective particles high in the atmosphere or making clouds brighter. The goal is to quickly cool the planet.

A couple of startups are already trying to deploy this untested technology or betting governments will eventually use it, while a cluster of Bay Area nonprofits are backing research into its planetary impact. With the world hotter than at any point in human history and emissions showing no sign of falling, the pitch is that dimming the sun is a relatively cheap way to turn the heat down.

“To get started it only takes one person to say, ‘I have 100 million quid, I have a business jet, let’s go,’” said Andrew Lockley, a UK-based independent researcher in the field scientists call geoengineering. “History will judge whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing.”

Reflecting sunlight to cool the planet — known as solar radiation management (SRM) — could come with dangerous consequences such as shifting rainfall patterns and changing the prevalence of diseases like malaria, to say nothing of the potential geopolitical chaos. Those risks have scientists urging caution and governments slowly working to build policies. But the tech world has rarely shied away from testing a new product and figuring out the bugs later, and prominent philanthropists are dedicating more money than ever to these radical ideas.

Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill Gates was one of the first billionaires to back scientists studying the topic more than a decade ago. Last year, OpenAI Chief Executive Officer Sam Altman expressed support for SRM research, and Silicon Valley abounds with speculation on whether he’s spending some of his AI fortune on it. A cohort of benefactors with ties to Meta Platforms Inc. — including former technology chief Mike Schroepfer, co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, and former executive and current venture capitalist Matt Cohler — have placed bets on blocking the sun. So too have Lowercase Capital founder Chris Sacca and hotel heiress-turned-Bay Area philanthropist Rachel Pritzker.

While most of the new interest comes from the tech world, some in finance have also started investing in geoengineering research. A recent $40 million commitment from the Quadrature Climate Foundation, a UK-based nonprofit tied to an investment company of the same name, is roughly on par with the US government’s entire funding for the field to date. The Simons Foundation, a New York-based philanthropy backed by late hedge fund billionaire Jim Simons, recently committed $50 million to SRM research.

Kelly Wanser, who spent much of her career founding companies in Silicon Valley before starting the nonprofit SilverLining, said the burgeoning interest in SRM makes sense for investors drawn to technological solutions to big problems — “the art of the possible,” as she puts it.

Many tech types turn to science fiction for inspiration, and in the case of geoengineering there’s a template: Neal Stephenson’s 2021 novel . The plot follows a Texas billionaire who takes climate matters into his own hands by building the world’s biggest gun to shoot particles into the sky to reflect incoming sunlight.

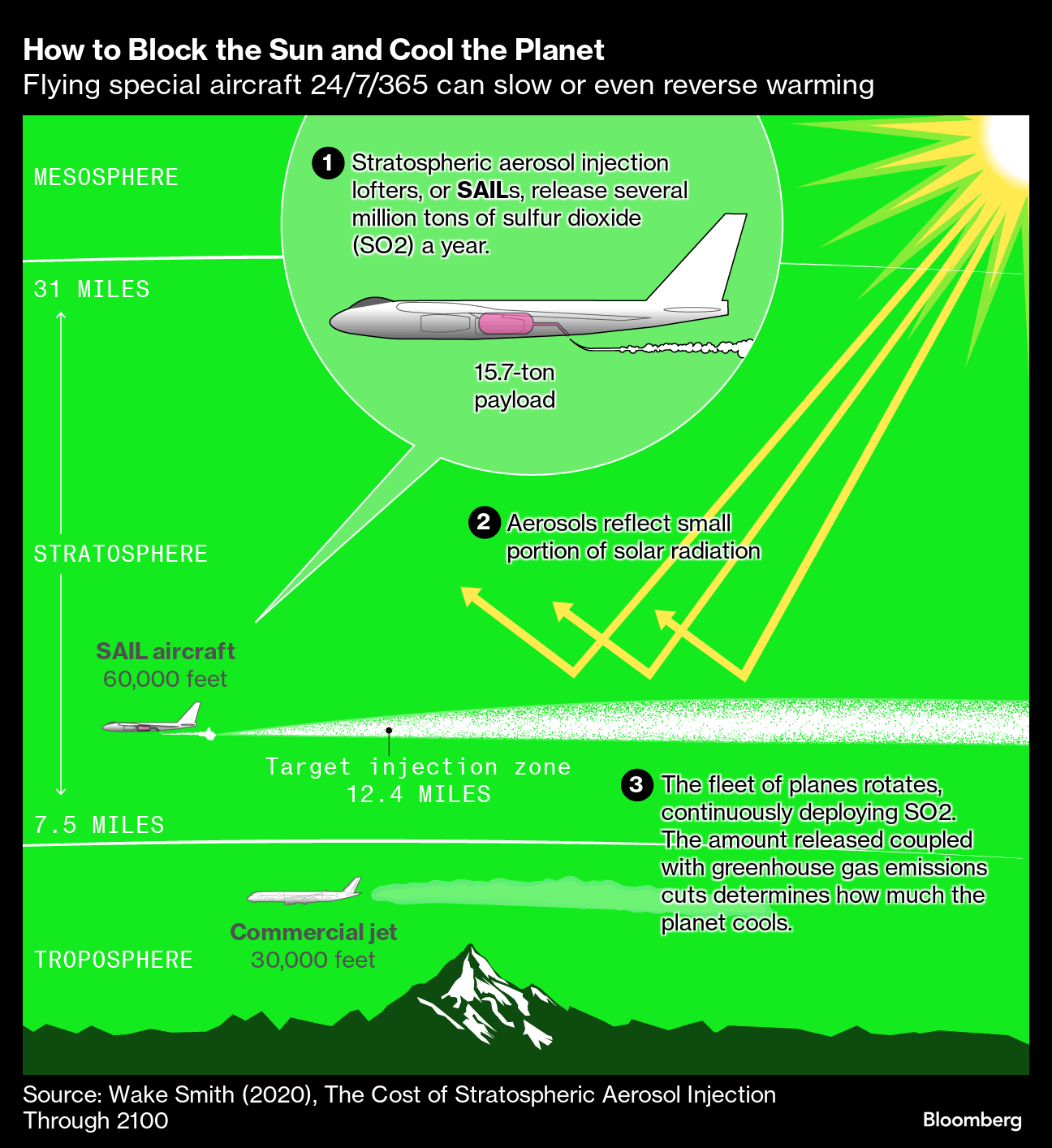

Most SRM research focuses on planes delivering sulfur dioxide to the stratosphere. At least one startup is already iterating on that concept. Luke Iseman started Make Sunsets after reading . The startup is already launching sulfate-filled balloons and sells “cooling credits,” akin to carbon offsets. It’s impossible to measure exactly what impact, if any, Make Sunsets has on the planet’s temperature.

Iseman is frustrated at the slow work on deploying SRM and dismisses anyone pushing to establish scientific consensus on impacts, develop governance structures and build public support. “I don’t understand why everyone is so focused on that,” he said. “I don’t think that step one for trying to do good should be to get international consensus.”

Two of his venture capital backers — Tim Draper of Draper Associates and his son Adam Draper of Boost VC — see Make Sunsets as a solution to legislators dragging their feet on climate action. “If you left it in the hands of the government, nothing would ever happen,” said Adam Draper. Make Sunsets has raised more than $1 million so far.

Not all SRM funders want to go as fast as possible. “The last thing the world needs is for rogue actors or companies to move society toward intervention without strong information and safeguards in place,” says Pritzker, who serves as president of the Pritzker Innovation Fund.

A spokesperson for Gates says he’s “invested billions” in emissions-cutting technology and adaptation. “At the same time, given the realities of the pace and potential impact of climate change, he’s also spending a small fraction to support basic research into interventions, including geoengineering, to ensure we fully understand the risks.”

SilverLining’s Wanser called Make Sunsets “ridiculous,” and others in the field hold the startup in similar disdain. She said multiple investors have asked for her view on the startup as well as Stardust Solutions, a two-year-old Israeli company that’s raised $15 million and plans to sell governments its planet-cooling technology. In both cases, Wanser believes it’s too early to be thinking about monetization: “You need a regulatory function that works and you need lots of science. Right now, we don't have either of those things.”

Many of the scientists studying SRM have prioritized transparency and gaining public trust. But Silicon Valley’s philanthropy culture can favor opacity. Take the LAD Climate Fund — a collection of three longtime Silicon Valley-ites Larry Birenbaum, Andrew Verhalen and David Schwartz — recently backed Environmental Defense Fund’s SRM research commitment, a first for the established nonprofit. “We are huge fans of transparency; anything that sheds more light on SRM is a good thing,” Schwartz wrote in an email before canceling an interview. None of the LAD members have responded to questions since.

A spokesperson for SilverLining said the group was “unable to share a full list of SilverLining's donors at this time,” though it lists major funders on its site.

Secrecy makes it hard to track the full flow of funding. But what’s clear is that it wouldn’t take much for a sufficiently motivated rich person to start a program. Wake Smith, a researcher with a background in aviation, has mapped out how much it would cost to inject sunlight-reflecting particles into the stratosphere in a 2020 paper. Spending as little as $7 billion a year would temporarily cut the Earth’s warming in half (an undertaking that would need to be combined with slowing and eventually slashing future emissions to last). That price tag is just a fifth of NASA’s budget.

Congress committed the first explicit funding for SRM research in 2020. Those dollars support modeling and research in labs, and developing the ability to detect any rogue SRM attempts in US territories. The European Union has funded research into geoengineering governance. But those efforts are still in the very early stages.

If rogue startup founders or billionaires decide to experiment without permission, it could create distrust and prevent SRM from being embraced. That’s one of the reasons technologists shouldn’t be making deployment decisions, said Shuchi Talati, the founder and executive director of the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering.

“This needs to be an actual public debate,” said Talati, whose nonprofit works with civil society organizations and policymakers across the globe. “If we don’t try to do this in a better way, it will happen in the worst way possible.”

Nearly every attempt at even small-scale experiments has been met with local resistance. In 2021, a project in the Swedish Arctic on Indigenous Saami territory led by Harvard University researchers and partially funded by Gates was set to be one of the first outdoor experiments. But no one consulted with the Saami, and pushback from environmental groups and Indigenous leaders came months before the planned test flight. It was eventually canceled.

“You can’t go to a place like the Arctic and move fast and break things,” said John Moore, a researcher at the Arctic Centre in Finland who works with the Saami.

While Silicon Valley is warming up to SRM, scientists have been researching it for more than 60 years. But it wasn’t until the late 1990s that two researchers in California, Ken Caldeira and Govindasamy Bala, modeled the climate impacts for the first time. The duo set out to put the proposition of SRM to rest, only to find that it might actually work.

This early research eventually caught the interest of Paul Crutzen, winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research on the ozone hole. He wrote in a 2006 paper that there was “little reason to be optimistic” about the ability to bring down greenhouse gas emissions, which meant SRM needed to be taken seriously.

“That was really the turning point,” said Caldeira, now a senior staff scientist emeritus at the Carnegie Institution for Science and an employee of Gates Ventures, the private office of Bill Gates. “When you have a Nobel Prize winner saying, ‘Look we need to take this seriously,’ people take it seriously.”

Nearly two decades later, however, SRM remains extremely controversial. Critics fear it will be an excuse to avoid eliminating fossil fuel use and worry the risks haven’t been fully studied. Real-world evidence from volcanic eruptions, which act just like giant sulfur guns, have shown that cooling the world too much, too fast can pose dangers. Crop failures in Europe and North America and excessive rains and cholera outbreaks in South Asia followed the 1815 eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora. The planet cooled so much that the aftermath was called the “year without a summer.”

For some, SRM research is beginning to feel like a race against the clock. “If there is a planetary emergency and if we need to bring the global temperatures down within a couple of years, the only option is solar engineering,” Bala said in an email.

Lockley, the independent researcher in the UK, is much more eager to conduct outdoor experiments than most. In fact, he claims to have “flown the first confirmed stratospheric geoengineering flight,” without permission from any regulatory body other than the UK Civil Aviation Authority. “And no one from the government has contacted me and no one has shot me yet.”

Working with aviation company European Astrotech, Lockley delivered a load of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere using high-altitude balloons, according to a paper he and a co-author currently have under review. Now he’s looking for someone with a bigger checkbook to advance his work: “Somebody in the billionaire class could easily come along in the next five years and do some climatically noticeable geoengineering.”

Lockley identified Musk as a prime candidate because of his “cavalier attitude and the experience in aerospace.” It wouldn’t even take rockets: Lockley points out that private jets can reach the stratosphere in some parts of the globe. With a personal fortune of $270 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Musk could finance years of SRM efforts.

But widespread deployment would likely exceed the capacity of any individual billionaire. On the most expensive end — in the scenario where the world ramps up carbon emissions even as it tries to reverse global temperatures to 2020 levels with SRM — the cost would be more like $71.7 billion a year. That still makes SRM “cheap, cheap, cheap,” said Smith, compared to other technologies such as removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

There are other obstacles. Gathering a fleet of sulfate-spewing planes would attract attention. “Before the planes took off with the first deployment load,” Smith said, “somebody would’ve taken their destroyer to that island and knocked on the door and said, ‘Can you kindly explain what you're doing here?’”

Yet it’s unclear whether the US government has any protocols for handling unauthorized SRM deployment. A spokesperson for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the only federal agency doing direct work on SRM, was not unaware of any. On a very small scale, of course, Make Sunsets is already doing it.

For sci-fi writer Neal Stephenson, there’s little pleasure in seeing his story made real. He said in an interview that anyone who plans on taking action based on the book first read it in full. “It’s certainly not a story in which SRM is deployed and everyone lives happily ever after,” he said.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

Musk Foundation-Backed XPRIZE Awards $100 Million for Carbon Removal

Nissan Commits Another $1.4 Billion to China With EVs in Focus

NextEra Energy reports 9% rise in adjusted earnings for Q1 2025 as solar and storage backlog grows

US Imposes Tariffs Up to 3,521% on Asian Solar Imports

India Battery-Swapping Boom Hinges on Deliveries and Rickshaws

China Reining In Smart Driving Tech Weeks After Fatal Crash

Japan Embraces Lab-Made Fuels Despite Costs, Climate Concerns

GE Vernova’s HA-powered Goi Thermal Power Station adds 2.3 GW to Japan

Used Solar Panels Sold on Facebook and eBay Have Cult Following