Brazil’s Net-Zero Transition Will Cost $6 Trillion by 2050, BNEF Says

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil, which already boasts one of the cleanest power sectors in the Group of 20, will need to invest $6 trillion from now until 2050 to speed up decarbonization across its entire economy.

This is the latest assessment from BloombergNEF, which finds that Brazil’s energy-related emissions must fall 14% by 2030, compared with 2023 levels, and drop 70% a decade later to be on a path to net zero.

In its New Energy Outlook report, BNEF says Brazil will need to put more money into abatement technologies like carbon capture and storage, but its biggest decarbonization challenge will be electrifying transportation, which currently represents more than half of the country’s energy sector emissions.

The analysis comes as Brazil prepares to host the annual United Nations climate conference, known as COP30, later this year. Countries at the summit will be asked to demonstrate their continued commitment to the landmark Paris Agreement, which pledges to keep global warming to well below 2C, and ideally 1.5C, relative to pre-industrial levels.

To meet its climate ambitions, Brazil will need to show it’s tackling deforestation and agriculture emissions, along with addressing energy transition issues, according to BNEF. Still, the analysis of Brazil’s power, transportation, industry and buildings sectors does not see a scenario where the country aligns with 1.5C.

At best, Brazil will be consistent with 1.75C of warming by 2100 if it fully decarbonizes its economy by midcentury, the report said. This rises to 2.6C in a base case scenario, assuming there’s no extra policy support for the transition, and economic development is based on the cheapest technology available.

Here are five main takeaways from the report.

Solar and wind are the future

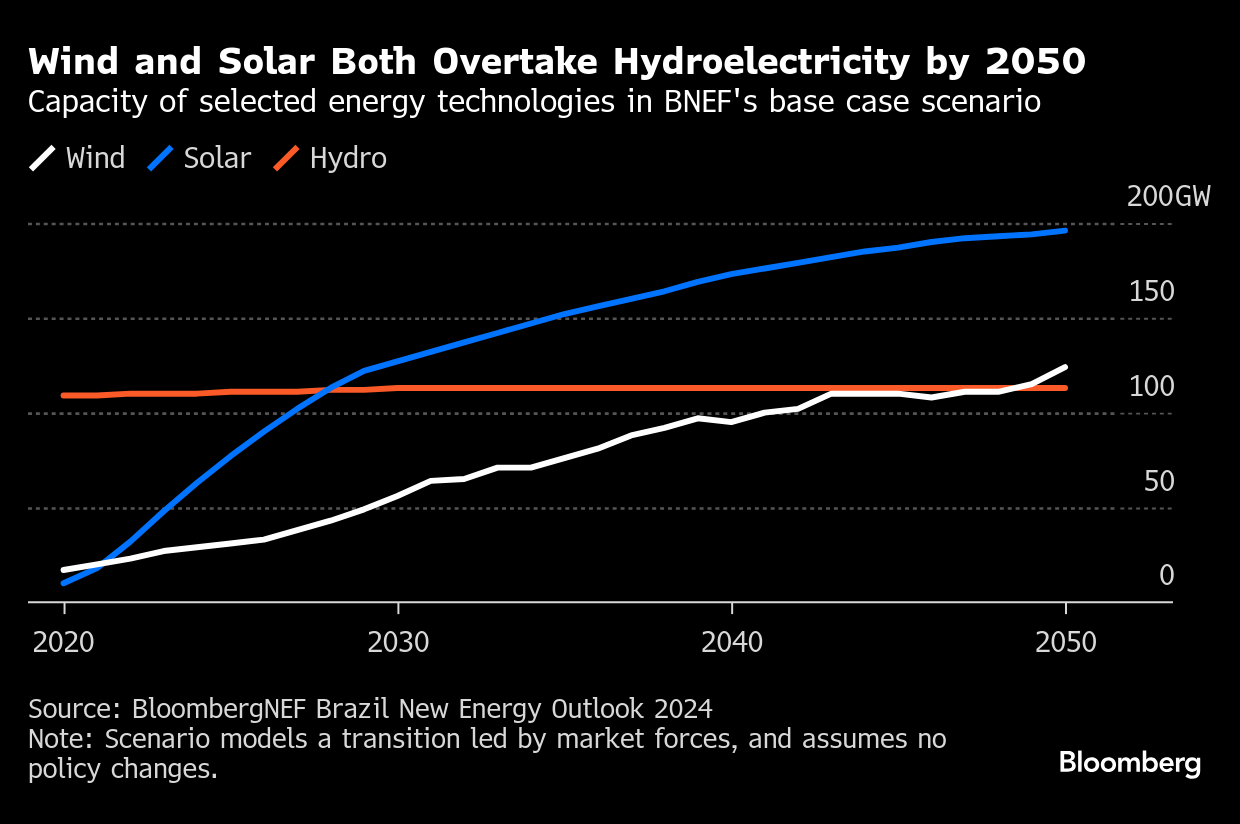

Brazil has been a pioneer in hydroelectric power, installing more than 100 gigawatts of capacity since the 1960s. But that is unlikely to continue. Its mega dams have been beset by issues including environmental damage and downtime when river levels are low. Now it’s the turn of wind and solar to pick up the mantle. Both are expected to rise significantly under a net-zero or base case scenario.

Around 90% of Brazil’s electricity generation in 2024 came from renewables. That sector is set to grow, largely because it’s cheap to expand wind and solar. Both are expected to overtake the supply from hydroelectricity by 2050.

“Brazil builds a lot of solar and builds a lot of wind, not only because it’s concerned with net zero, but because it’s cheaper than building gas,” said Vinicius Nunes, a BNEF research associate and the report’s author. “Gas is not cheap in Brazil, oil is not cheap in Brazil, but solar and wind are the cheapest source of electricity. So even if you’re not aiming to net zero, economically-wise it makes sense to build renewables.”

Energy is half the battle

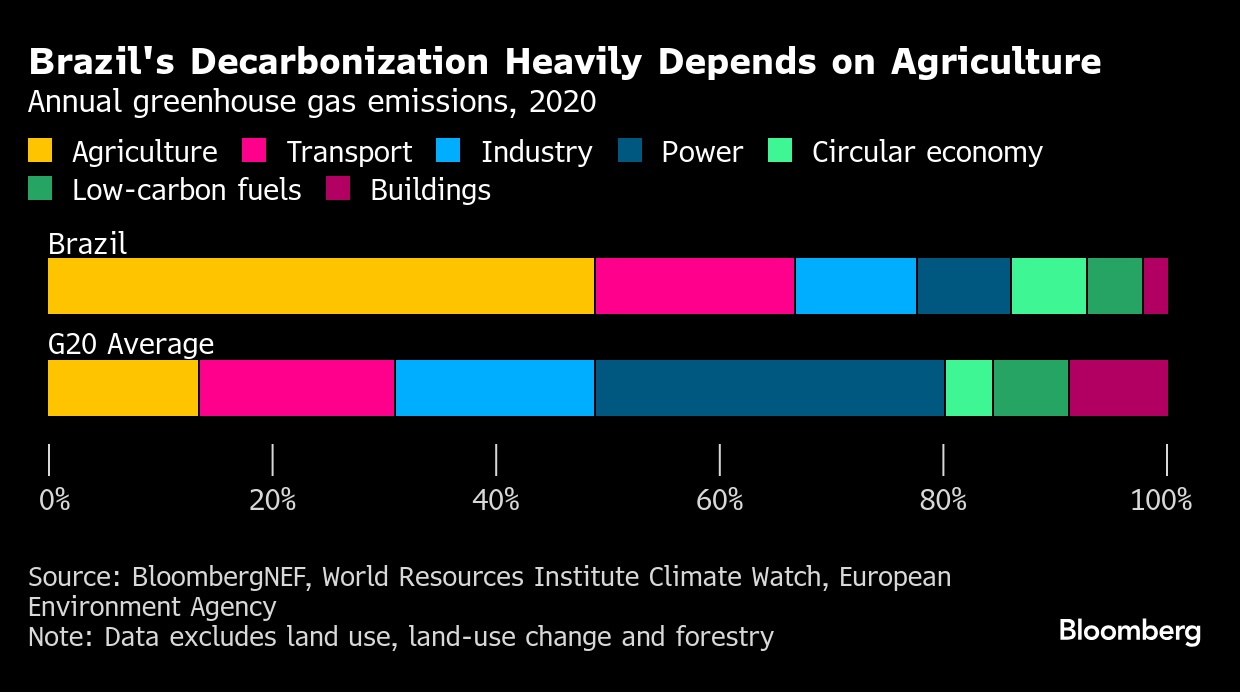

While Brazil’s power sector is almost entirely decarbonized, fossil fuels are still widely used in other sectors like transportation and industry.

“Brazilians tend to think that because the power sector is already decarbonized, you don’t have a lot of energy emissions. But that’s not the case at all,” Nunes said. “Half of Brazil’s final energy consumption is still fossil fuel. So tackling emissions in the energy sector is still a big thing for Brazil.”

Also on Brazil’s emissions radar: the country’s thousands of acres of farmland and its Amazon rainforest, one of the world’s most important carbon sinks. There is no path to net zero without tackling farming emissions and deforestation. When looking at Brazil’s total greenhouse gas emissions, agriculture and land-use change together account for 63%.

Coal, oil and gas already peaked

In Brazil, the usage of all three fossil fuels has already peaked in either a net-zero or base case scenario, the report said. But fossil fuels are still projected to be part of the picture in 2050 regardless.

The future trajectories of the three fuel types look quite different. For gas, under a base case scenario, demand will fall and then rise again as industrial sectors that currently rely on oil and coal switch over.

For a plan aligned with net-zero goals, oil drops close to zero by 2050 as electrification takes over in earnest. For coal, there is no economical way for industries like steel and aluminum production to move away from the fuel in the short term, causing a plateau in a base case scenario. Power sector demand for coal, meanwhile, drops quickly because of cheap renewable energy.

Nunes said political risk to energy decarbonization is relatively low and a US-style backlash happening under Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, or a future leader, is unlikely. Even under Lula’s predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, who was not a climate-forward leader, the renewable energy industry suffered little. “It’s an economically good industry for the country. So there’s not that much pushback in Brazil because of that,” Nunes said.

EVs will clean up a lot of emissions

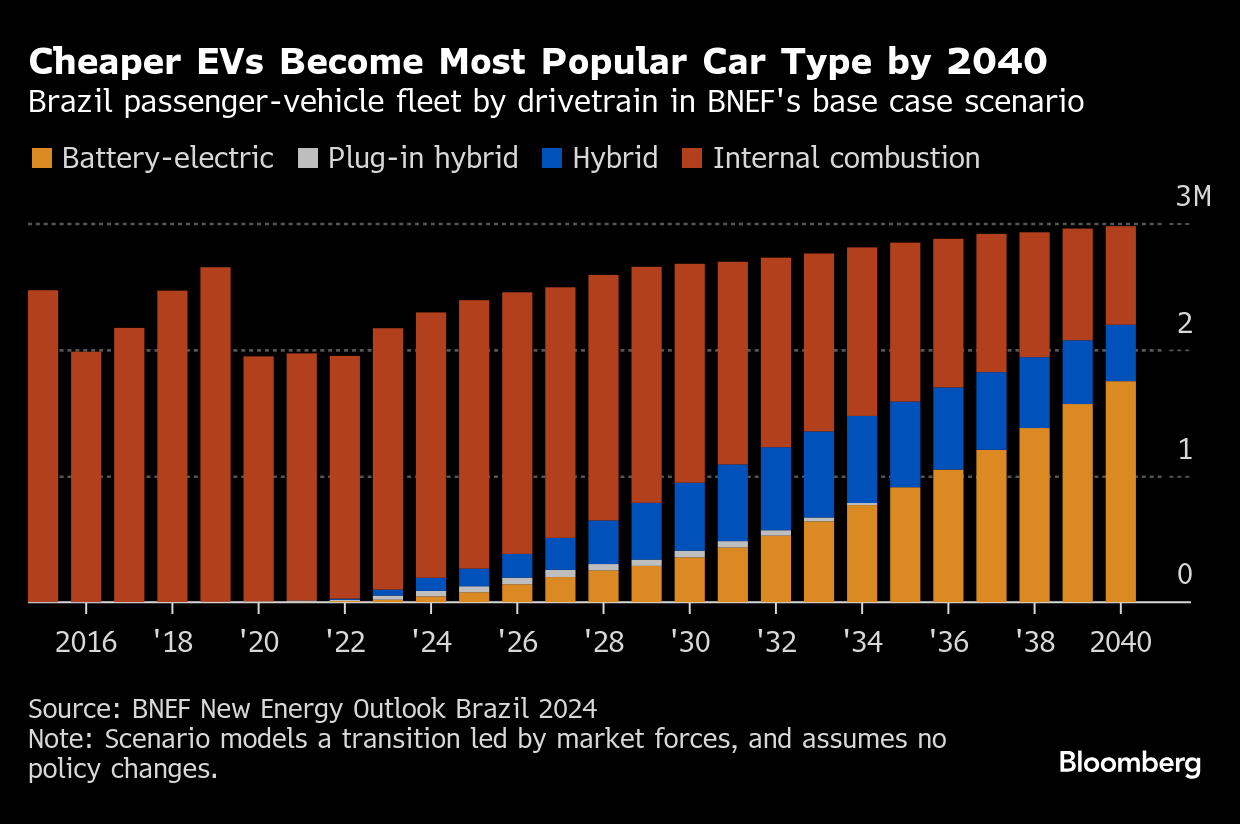

Since the power sector is already so far ahead, road transportation presents the most significant challenge for decarbonization. “This sector in Brazil is the one that needs to drop emissions faster in order for Brazil to be on a pathway to net zero,” Nunes said.

Biofuels are used much more widely in Brazil than in most other countries. A program started in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis created a domestic ethanol industry, and most cars in the country can now run on gasoline, ethanol or a blend. Brazil is the second-largest ethanol exporter in the world.

But over the next 20 years, electrification is expected to become increasingly dominant for passenger cars, largely down to price. Battery-electric vehicles made up just 1% of sales in Brazil in 2023 and that figure will soar to 59% by 2040 even in a base case scenario, according to BNEF.

Still, the biofuels industry is expected to keep growing to meet demand in other sectors that can’t be easily electrified, particularly fuel for shipping and aviation. Brazil is likely to become a major exporter of biofuels to regions like Europe which have strict mandates for fossil fuel alternatives in aviation but little capacity to produce this themselves.

Net zero is only a little more expensive

Overall, BNEF’s net-zero scenario only costs around 8% more than the cheapest methods for developing the economy from 2024 to 2050. The policy and market intervention needed for technologies like carbon capture and storage and sustainable aviation fuel represent some of the extra investment requirements.

The base case analysis does not take into account the running costs of a fossil fuel-based system, just the capex investment. It also doesn’t calculate the extra expenses for adaptation in a 2.6C world compared to a 1.75C world, which would make investing in climate action even more worthwhile, the report said — meaning it may soon be cheaper for Brazil to transition to a net-zero economy than not to, said Nunes. “If you're building that many more renewables, you’re not building that many fossil fuels,” he said. “So one thing compensates the other.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GB Energy Faces New Doubts as UK Declines to Affirm Future Funds

Korea Cancels Planned Reactor After Impeaching Pro-Nuke Leader

SolarEdge Climbs 40% as Revenue Beat Prompts Short Covering

EU to Set Aside Funds to Protect Undersea Cables from Sabotage

China Revamps Power Market Rules In Challenge to Renewables Boom

KKR increases stake in Enilive with additional €587.5 million investment

TotalEnergies and Air Liquide partner to develop green hydrogen projects in the Netherlands

Germany Set to Scale Down Climate Ambitions

Shipping Giants Ask Watchdog to Avoid Biofuels in Green Push