Global Warming Could Be Making It Less Windy in Europe

(Bloomberg) -- Global warming is driving down wind speeds during European summers, putting additional stress on the region’s energy systems as soaring temperatures boost cooling demand, new research shows.

That phenomenon — known as “stilling” — is driven by amplified warming of both the land and the troposphere, the layer of atmosphere closest to the earth’s surface, said lead researcher Gan Zhang, a climate scientist and professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The decline in wind speeds, which is also occurring in other northern mid-latitude regions such as North America, is projected to be less than 5% over the period from 2021 to 2050. But even small drops translate into major swings in wind power generation, according to Zhang.

“The energy system is a marginal market,” Zhang said. “That means if you change the margin by 5 to 10%, the price response can be huge.”

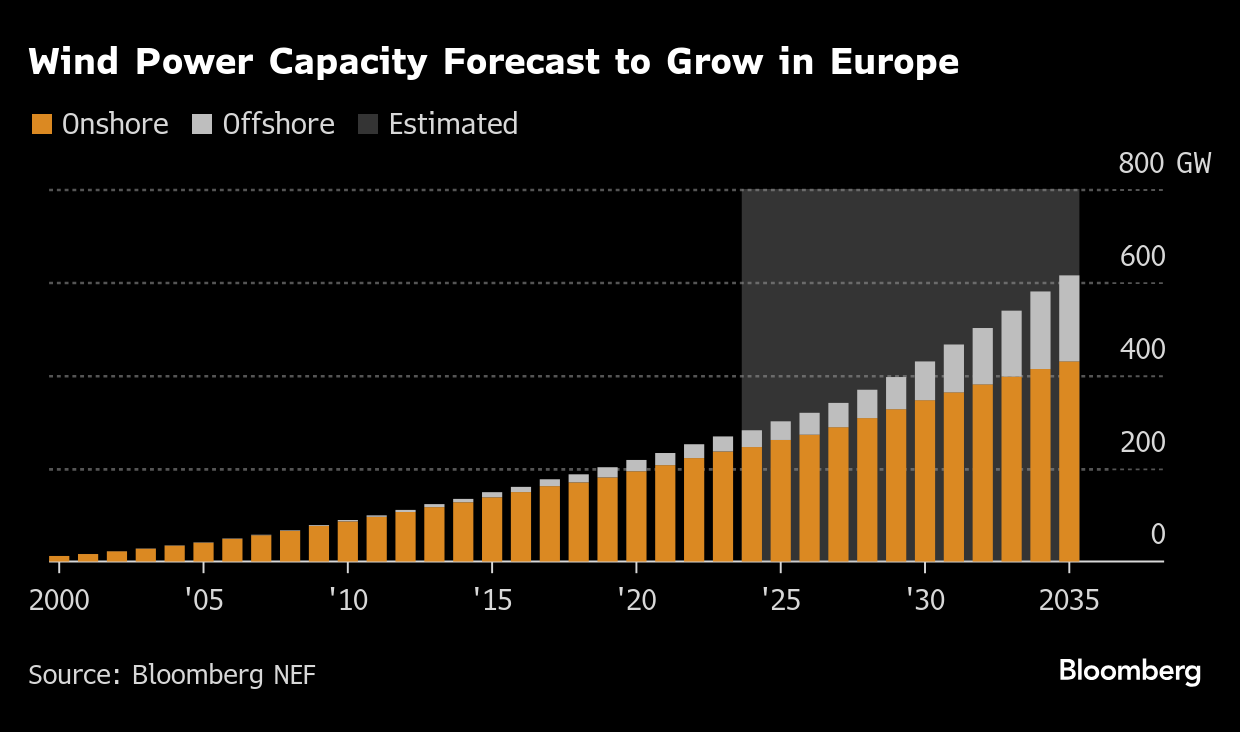

Lower wind speeds underline the challenge for European nations that have switched away from fossil fuels and nuclear power to intermittent renewable energy, and potentially put the region’s climate goals in jeopardy. Freezing temperatures and windless days this winter have depleted the region’s gas inventories, although so far there isn’t reliable data to show that this is also related to climate change.

The ripple effects of even small declines in wind speeds highlight a fundamental shift in Europe from a temperature-dependent energy market to one determined by the wind and the sun, according to Christopher Vogel, a wind and tidal power researcher at the University of Oxford.

“How things are behaving really is driven by, ‘is it sunny, is it windy?’” he said.

Vogel said the new research on “stilling” during the summer lines up with other studies that suggest the effect of climate change on wind will become statistically significant in the second half of this century. But it’s still unclear how shifts in average wind speeds will affect future energy production, and part of that uncertainty is because even the gold standard climate datasets “aren’t great at capturing extremes” in wind speeds, he said.

Unlike temperature and precipitation records, there’s a lack of robust historical wind data on which to model future climate outcomes, said Vogel, who studied the 2021 wind drought that forced the UK to restart mothballed coal plants. Wind measurements are also highly localized and easily thrown off by topography and buildings — even wind farms themselves, he added.

Despite the lack of data, Ivan Føre Svegaarden, whose Norway-based TradeWpower AS provides weather and climate advice to energy traders, believes European wind power production is already seeing signs of a climatological downturn.

“The dominant high pressures are coming more often, they’re emerging more often, they last longer,” he said.

Recent Data

The trends become clearer by putting less weight on older historical climate data and more emphasis on a smaller batch of recent measurements, which more accurately reflect the atmospheric changes Europe has experienced due to record warming, Svegaarden said.

Zhang at the University of Illinois said his research team worked around the lack of historical data by using multiple datasets and running simulations that found an increase in summer “stilling.”

While Svegaarden said declining wind speeds suggest European Union policymakers may have put too much reliance on that form of generation to meet its clean-energy goals, Zhang is more optimistic. Even with declining speeds, wind can be a key part of the energy mix for most countries, he said.

Still, both Zhang and Vogel suggest that Europe may need to be more creative in renewable power development — dispersing generation assets, building more interconnectors and having back-up sources of electricity — to offset the challenges presented by downturns in wind power.

“You can’t just rely on wind to solve the UK’s electricity problems all year round, particularly if there’s a shift in when that demand is going to be peaking throughout the year,” Vogel said.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

Want Solar Panels on Your Roof? How to Navigate Market and Tariff Chaos

New Danish Nuclear Power Fund Targets Raising €350 Million

US Green Steel Startup Raises $129 Million Amid Trump Tariff Uncertainty

Spain Signals Openness to Keeping Nuclear Power Plants Open

Musk Foundation-Backed XPRIZE Awards $100 Million for Carbon Removal

As Tesla Falters, These New EVs Are Picking Up the Pace

Fashion Is the Next Frontier for Clean Tech as Textile Waste Mounts

High-Powered Solar Cells Are Poised to Replace Batteries

New Jersey Forest Fire Shuts Stretch of Garden State Parkway