Inside the LA Fire Cleanup's Rush to Remove Tons of Toxic Rubble

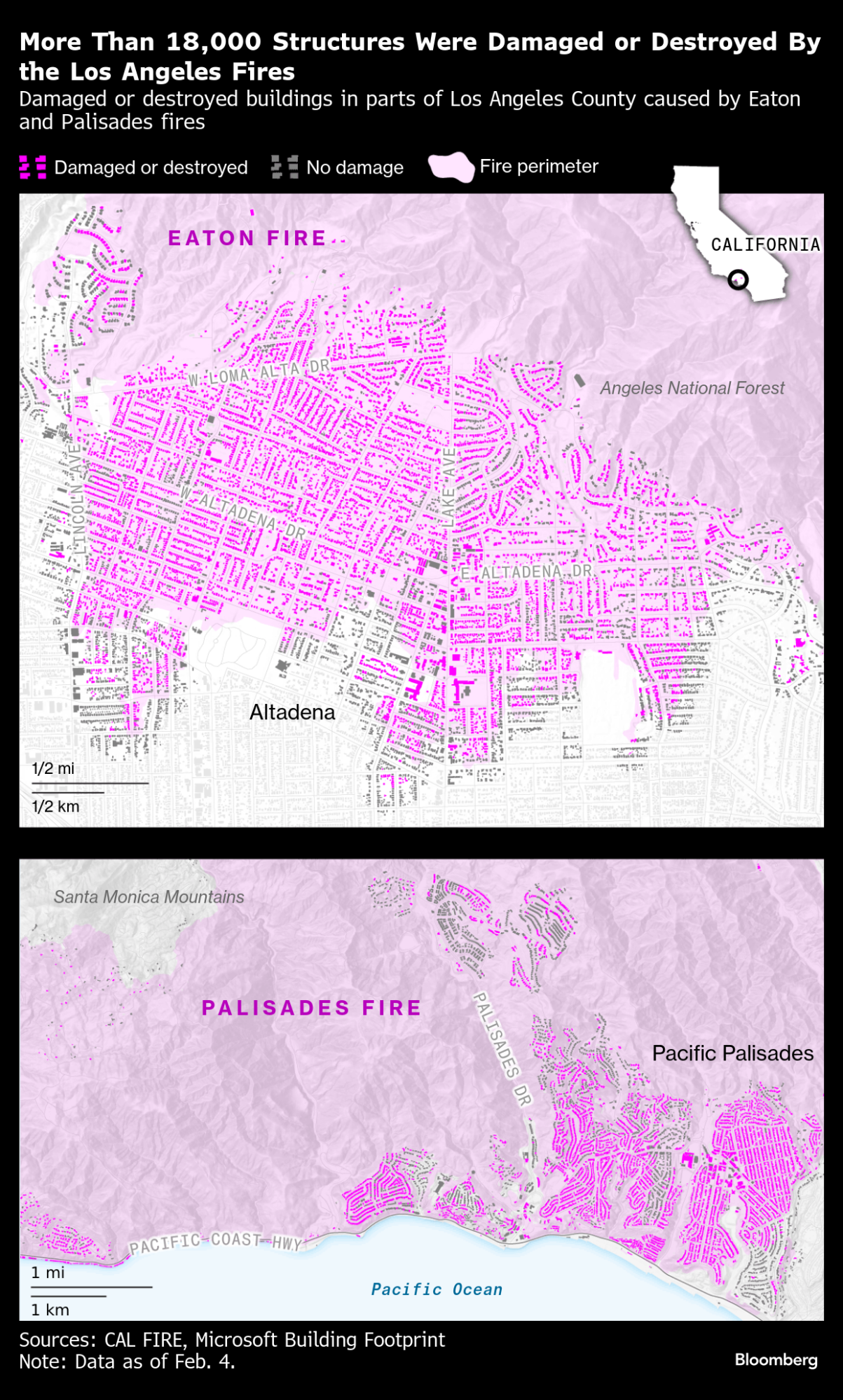

(Bloomberg) -- Removing toxic waste from the foothills and coastal canyons where more than 16,000 homes and businesses burned down in the Los Angeles wildfires was always going to be an unprecedented challenge in a densely-populated, traffic-choked metropolis. And then the Trump administration ordered the job to be completed in just 30 days.

Federal officials revealed the deadline on Jan. 29, days after President Donald Trump met with survivors of the Pacific Palisades fire. The US Environmental Protection Agency said that it’s been “tasked” with finishing the household hazardous materials cleanup within a month.

But the vast scale of the damage is testing the government’s well-honed wildfire playbook and signals the growing challenge of responding to ever-more frequent and destructive climate disasters. It took the EPA more than three months to remove hazardous debris from 1,448 residential and commercial properties incinerated in the 2023 Lahaina wildfire in Hawaii.

LA has nearly 10 times the number of destroyed buildings and at least five times as many potentially explosive electric vehicles abandoned in fire zones that must be disarmed. “We find that the majority of residences and commercial structures that we address will have some sort of hazardous material on the property, even if it's fully burned,” Tara Fitzgerald, the EPA incident commander for the LA wildfires, said in an interview.

Hundreds of thousands of pounds of pesticides, paints, asbestos, fuel tanks and other toxic household items must be located amid the rubble of thousands of homes. Routes must be planned for fleets of trucks to haul away the hazardous waste. The handling of explosive lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles and home energy storage systems requires dispatching specialized teams.

Appropriate sites must be found to receive all that toxic waste and temporary facilities built to sort and package it for safe transport to disposal sites, which also must be lined up. That’s just Phase One of the cleanup. In Phase Two, the rubble—trees, walls, chimneys, foundations—will be removed and transported to landfills. Most properties are likely contaminated with toxic ash, so half a foot of soil will be excavated from the ruins. Last week, US Army Corps of Engineers officials projected that 80% to 90% of properties in Phase Two will be cleared of debris and ready for reconstruction in a year or less; that’s after an original estimate of 18 months.

The costs are likely to be immense: The Federal Emergency Management Agency pegs the price of debris removal at $3 billion and economists at the University of California at Los Angeles estimated this week that total property and capital losses from the fires will be as much as $164 billion. The federal government under President Joe Biden agreed to pay for initial cleanup costs. traveled to Washington this week to meet with US Congress members and Trump to try to secure additional funding for the recovery.

That’s left the EPA scrambling to find more processing sites in the face of opposition from communities that are hosting the facilities and fear contamination from burn sites.

“My concern is that I feel like they’re rushing your team, and when you are rushed to do something, there is a big risk of human error,” Cesar Garcia, mayor of the Los Angeles County city of Duarte, told Fitzgerald at a raucous town hall meeting held last week. Garcia and other local leaders called the gathering in Duarte after they discovered the EPA had opened a hazardous waste processing station near their communities about 15 miles from Altadena, where the Eaton Fire incinerated some 9,400 structures.

“Regardless of the speed that we work, we do have to do the work safely,” Fitzgerald said over angry shouts of “We don’t want it! Go somewhere else!” from the audience.

It’s one of two facilities initially planned to process and package hazardous materials for disposal. A second site just outside Malibu is handling toxic debris from more than 6,800 buildings that burned in nearby Pacific Palisades. On Friday, Malibu residents staged a protest at the oceanside depot. Dressed in protective gear and carrying signs that said “No Toxic Debris at Topanga Lagoon” and “Surfers Unite, Protect Water,” they demonstrated across from beaches closed due to toxic runoff from the wildfires.

At the meeting in Duarte, Fitzgerald emphasized that the agency has successfully removed hazardous waste from many destructive wildfires over the past decade.

The LA wildfires, however, present unique challenges.

In Pacific Palisades last Thursday, a cleanup crew carefully tread through the remains of multimillion-dollar homes so obliterated that only chimneys distinguished one property from another on streetscapes reduced to rubble. It was the fourth day of the Phase One hazardous waste cleanup and by the weekend as many as 1,000 workers would fan out to locate and remove ordinary household items turned toxic by the wildfires’ extreme heat.

Clifford Franklin, 74, returned to Altadena two weeks ago to discover his home partially razed by the Eaton Fire. The roof had collapsed onto his garage, and half of the house was gone, as were the rest of the dwellings on his block. A yellow tag hung on the front door warning Franklin not to enter the garage, where he had stored paint, aerosol cans, a big-screen television and a propane grill.

“You could smell the toxicity,” said Franklin, who like many other Angelenos is concerned about the hazards.

Southern California Edison said on Thursday that it’s examining the possibility that retired transmission equipment ignited the Eaton wildfire, according to a regulatory filing.

Franklin is particularly worried about his neighbors’ electric cars that burned in the inferno. Some 400,000 electric vehicles are registered in Los Angeles County, and the proliferation of highly flammable lithium-ion batteries in EVs and home energy storage systems has complicated cleanups. Specialist teams are needed to defuse what EPA officials describe as “unexploded ordnance.”

The 2023 Lahaina wildfire that leveled the historic Maui town was the first conflagration where cleanup crews encountered a significant number of electric cars, according to Chris Myers, the EPA’s lithium-ion battery technical specialist for the LA fires. They processed 94 vehicles in Hawaii; Myers expects to find more than 500 electric cars, including hybrid vehicles, in the LA burn zones.

A fire-damaged battery pack can emit toxic gases or ignite days, weeks or months after a wildfire. “It’s a very, very unpredictable situation,” said Myers on Thursday as he stood outside the ruins of what once was a sprawling $7 million modernist home overlooking a canyon in Pacific Palisades. A charred Tesla Model Y sat in the driveway framed by scorched palm trees.

A reconnaissance team had spray-painted blue lightning bolts on the Tesla to alert cleanup crews to the presence of a battery pack. A Toyota Prius next door and another one across the street also bore blue bolts. While Tesla’s have distinctive shapes that are easily recognizable even when only a shell is left, other vehicles require further investigation to determine if what looks like a gasoline car actually is an electric or hybrid version of the model.

Typically it takes an eight-person squad to remove a car’s battery pack. Four people wearing respirators, hard hats, gloves and other protective clothing surrounded the Model Y while others stood 75 feet away. “If something goes bad, we're going to hear a pop” of toxic gas, said EPA official Stephen Ball. After a worker sawed through the car’s roof pillars, another in a backhoe lifted off the top and crushed the body. The backhoe operator then flipped over the chassis so thousands of shotgun shell-shaped battery cells could be removed and stored in black buckets.

Cells that could still ignite are wrapped in fire blankets for transport to the Malibu processing center where the batteries will be soaked in a brine solution to deenergize them. A machine will shred the batteries for disposal at a recycling center or landfill.

The crew then convoyed to the ruins of an Arts and Crafts-style home a few blocks away where records showed that two Tesla Powerwall lithium-ion battery storage systems had been installed on the northeast corner of the house. No walls remained, however, and there was no sign of the Powerwalls, which could be buried under piles of debris.

That rubble will be removed in Phase Two of the cleanup, overseen by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Once the EPA certifies a property is clear of hazardous waste, contractors move in to haul away burned trees, walls, foundations and toxic ash. There’s no charge to homeowners but they can opt to hire their own certified contractors to remove debris. Once Phase Two is completed on a property, homeowners can begin rebuilding.

When a house burns at high temperatures, toxins in plumbing, nails, sheetrock, appliances and electronic gadgets vaporize and then condense, binding to ash. “It’s a nasty mix of stuff, mostly metals,” said Anthony Wexler, director of the Air Quality Research Center at the University of California at Davis. Ash from the LA fires fell across the city and as far as 100 miles off the coast.

“One thing I’m concerned about in LA are the ubiquitous leaf blowers that are going to put that ash back up into the air,” added Wexler.

A study of the 2021 Marshall Fire in Boulder County, Colorado, found elevated levels of toxic metals from the 1,000 houses that burned. The ash contained 22 times more copper, three times more lead, twelve times more nickel and two times more chromium than surrounding soil. Lead exposure has been linked to learning disabilities while chromium is associated with lung cancer, kidney and liver failure and other health effects.

In the LA burn zones, Corps contractors will remove six inches of ash-contaminated soil from the ruins of homes as well as from several feet surrounding the foundation. The ash will be “burrito-wrapped” in plastic liners and transported by truck to a disposal site.

The logistics are daunting, officials acknowledged, as heavy equipment must share narrow, traffic-clogged hillside and canyon roads with crews repairing utility infrastructure and contractors rebuilding homes. “It’s absolutely more challenging than other disaster areas that Corps of Engineers have worked at,” said Col. Brian Sawser, commander of the Corps emergency field office in Los Angeles.

Inevitably, there will be delays. As of Wednesday, the agency had certified 947 homes as cleared of hazardous waste and ready for debris removal. But crews couldn’t access another 1,456 properties because of dangerous conditions that require the Corps to first remove obstacles like tottering trees and walls.

“Those hazards should not be underestimated,” another Corps cleanup officer, Col. Eric Swenson, said at a recent meeting with Palisades residents. “There’s going to be some bumps in the road” to recovery.

(Updates the 18th paragraph with details aboutEdison probing a retired power line as a possible start of the Eaton Fire.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

Musk Foundation-Backed XPRIZE Awards $100 Million for Carbon Removal

Nissan Commits Another $1.4 Billion to China With EVs in Focus

NextEra Energy reports 9% rise in adjusted earnings for Q1 2025 as solar and storage backlog grows

US Imposes Tariffs Up to 3,521% on Asian Solar Imports

India Battery-Swapping Boom Hinges on Deliveries and Rickshaws

China Reining In Smart Driving Tech Weeks After Fatal Crash

Japan Embraces Lab-Made Fuels Despite Costs, Climate Concerns

GE Vernova’s HA-powered Goi Thermal Power Station adds 2.3 GW to Japan

Used Solar Panels Sold on Facebook and eBay Have Cult Following