Trump’s Climate Rollback Starts Now. It Can't Erase US Carbon Cuts

(Bloomberg) -- As Donald Trump begins another term as US president, environmentalists are dreading the effects of his vows to “drill, baby, drill,” yank the US out of the Paris Agreement, end tax credits for electric vehicles and more.

But climate and energy data from Trump’s first term cuts two ways. At least some of these promises will be met, slowing US progress on reining in greenhouse gas emissions. Yet there are clear indicators that a climate skeptic in the White House can’t completely undo the nation’s roughly two-decades-long decline in emissions.

Whatever Trump does, “it’s not going to change this fundamental trend,” says Billy Pizer, president and CEO of the environment-focused research nonprofit Resources for the Future.

That’s because there are simply too many other factors contributing to decarbonization inside and outside the country’s borders, from fluctuating economic growth to interest rates to the emergence of new technologies. There are also the ever-intensifying impacts of climate change itself. Stronger and more frequent wildfires, floods, hurricanes and heat waves are prompting continued momentum in some US states and cities, other countries and the private sector to reduce their climate risk.

But not every external factor tilts in favor of climate action — for example, the rising electricity demand tied to growing AI use and data centers that didn’t really exist last time Trump was in office.

Moreover, Trump doesn’t have to reverse or even pause US emissions declines to tip the scales towards more catastrophic levels of warming. At a time when the entire world, not just the US, is already behind on tackling climate change, any further slowdown guarantees more warming, meaning more devastating disasters. If and when climate action picks up again in the future, Pizer warns, “it may be more chaotic and expensive.”

To best understand where US emissions stand as Trump takes office again, and where they could go over the next four, 10 or 20 years, it’s helpful to first look at the past.

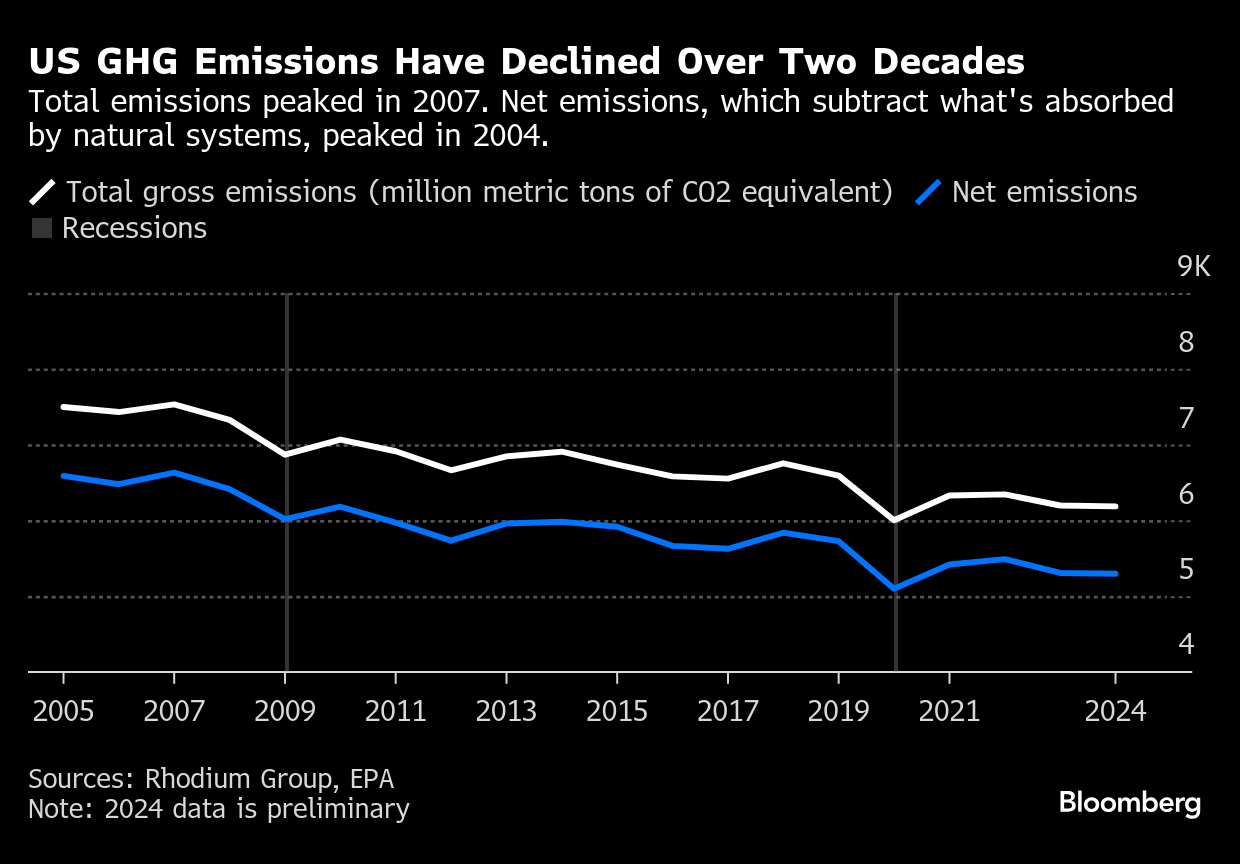

Total gross US emissions peaked in 2007 and have been largely declining ever since. But two years in particular “really stand out” — 2009 and 2020, says Catherine Wolfram, an applied economics professor at MIT Sloan School of Management who briefly served as deputy assistant secretary for climate and energy economics at the Treasury Department under outgoing President Joe Biden. Those two years were both marked by economic recessions, the latter caused by the global Covid-19 pandemic during the final year of Trump’s first term. Both times, US emissions dipped dramatically, showing how “energy and economic growth are so intimately intertwined,” Wolfram explains.

“We don’t want to decarbonize by shutting down the economy,” she says, so the challenge is decoupling economic growth from emissions.

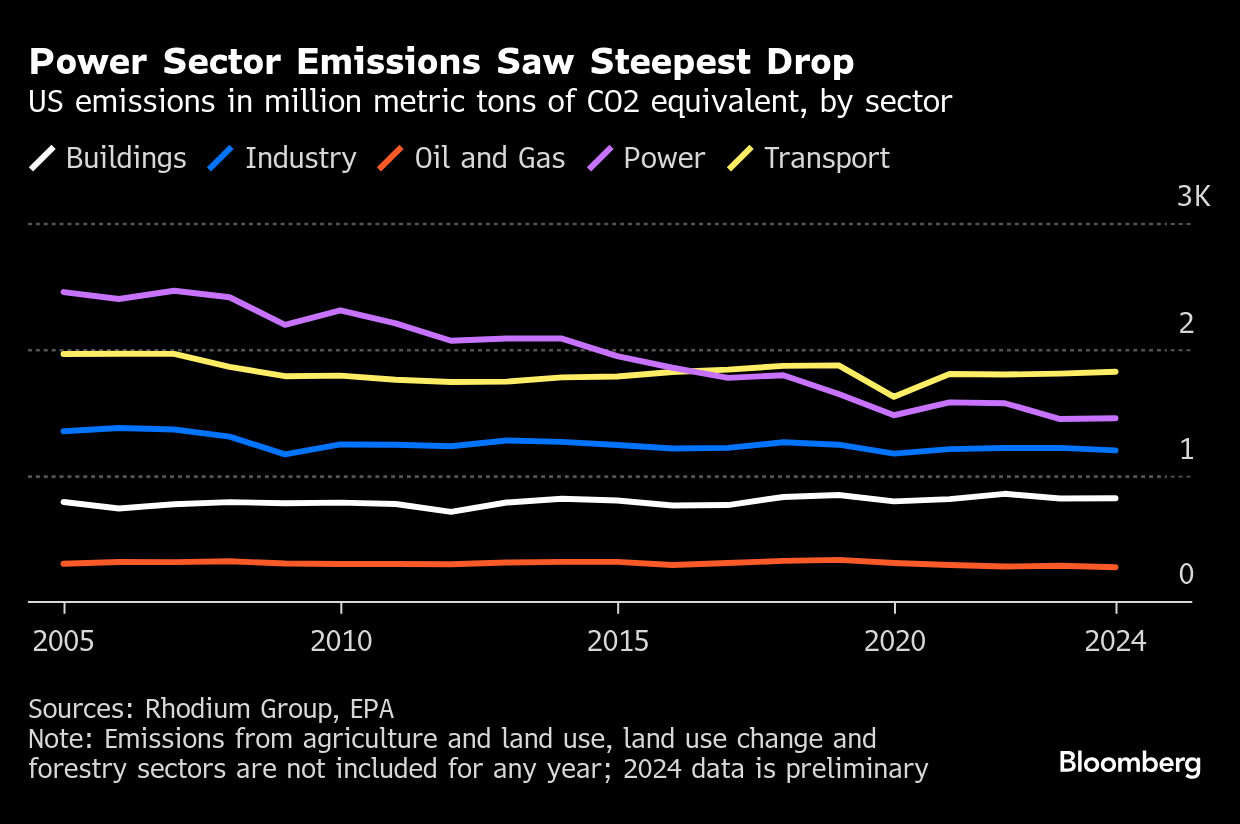

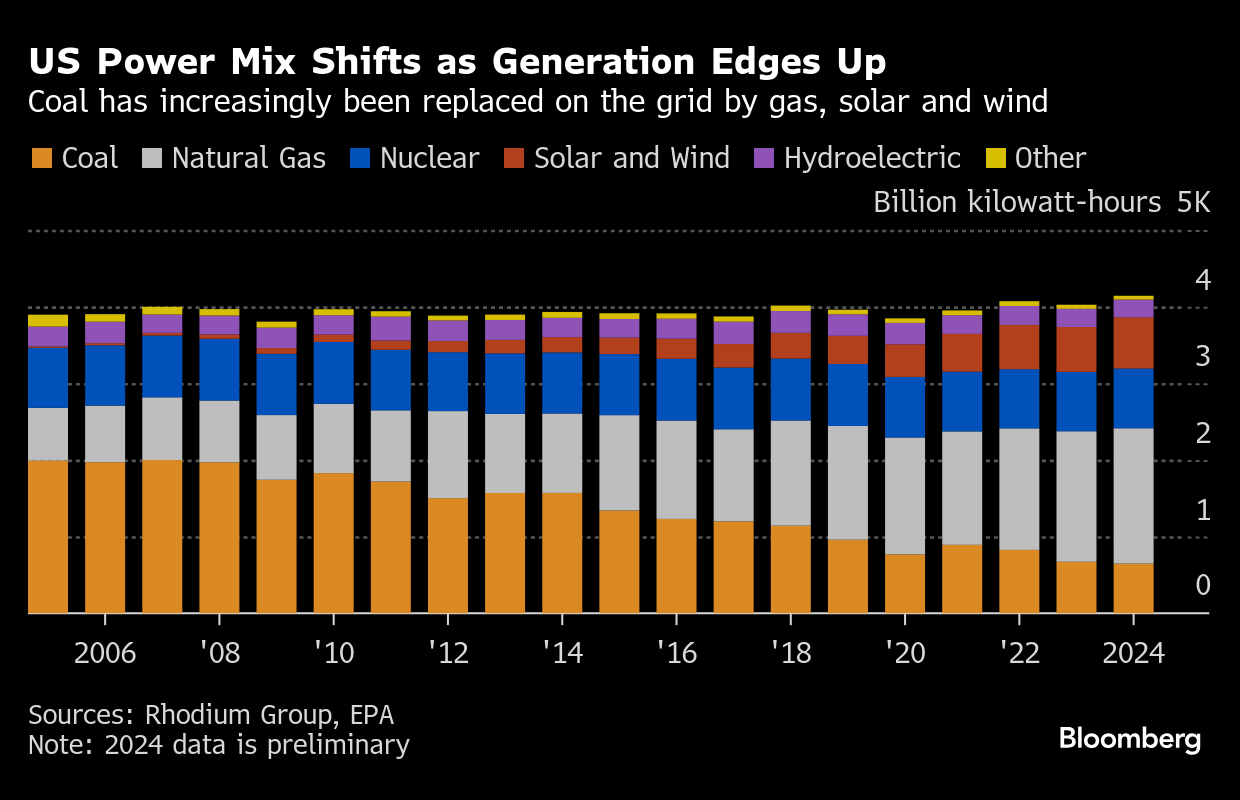

Looking at the longer-term trend, there’s one primary driver behind the recent declines: the shift away from coal in the power sector. The fracking revolution that started in the mid-2000s led to the rise of cheap natural gas, says Ben King, associate director of Rhodium Group’s energy and climate practice, causing gas to increasingly displace the more carbon-intensive coal as an electricity source. These economics continued to drive the shuttering of dozens of coal plants through Trump’s first administration.

At the same time, there was also “increasing availability of renewable resources like wind, solar and batteries,” King says, as the costs of these technologies came down in price faster than anticipated and low interest rates made it more affordable for developers to pay the high upfront costs of building big renewable projects. According to Rhodium’s preliminary 2024 greenhouse gas emissions estimate, last year was the first time when solar and wind combined surpassed coal on the US grid.

During Trump’s first term, “we got lucky,” says Wolfram. “We won’t get so lucky next time because we’ve driven out a lot of coal already,” she adds.

On top of further reductions in coal, steep declines in the power sector will increasingly come from renewables out-competing gas, but it will be tough for clean power sources to best gas without policy measures when gas is so cheap. That’s why the Biden administration took several steps to encourage the buildout of renewables, including approving 11 offshore wind projects that would collectively generate more than 19 gigawatts.

This is one area where Trump could have a chilling impact. He does not like wind, and he’s reportedly considering temporarily halting new offshore wind projects. Analysts at research firm BloombergNEF don’t see this as an idle threat, cutting their US offshore wind projections for 2024 to 2035 by 29%.

Another factor complicating what may happen with power sector emissions under Trump is the growing demand for electricity, driven in part by hotter summers and the rapid growth of AI and data centers.

This was apparent last year, when overall emissions only dropped 0.2% and power emissions actually ticked up. A big reason why is that last summer was especially hot, explains King, meaning there was high power consumption in homes, and to a lesser extent in commercial buildings, including data centers. “If it weren’t a hot summer, I have every expectation that [power] emissions would have decreased instead.” But at this point, hotter summers aren’t going away with climate change, and interest in AI and data centers is only climbing.

Apart from the power sector, emissions for all the other major sectors — transportation, buildings, industry — have largely “been idling along, with little variations here and there,” says King.

That’s at least somewhat due to weak federal climate policy until Biden took office, which allowed these industries to neglect their emissions, says Noah Kaufman, a senior research scholar at Columbia University. Some of the big climate moves under the Biden administration were designed to start changing this, especially in the transportation sector, like new vehicle pollution standards and the consumer incentives for EVs in the Inflation Reduction Act. Such efforts matter because as US power sector emissions have declined, the transportation sector became the nation’s top source of emissions.

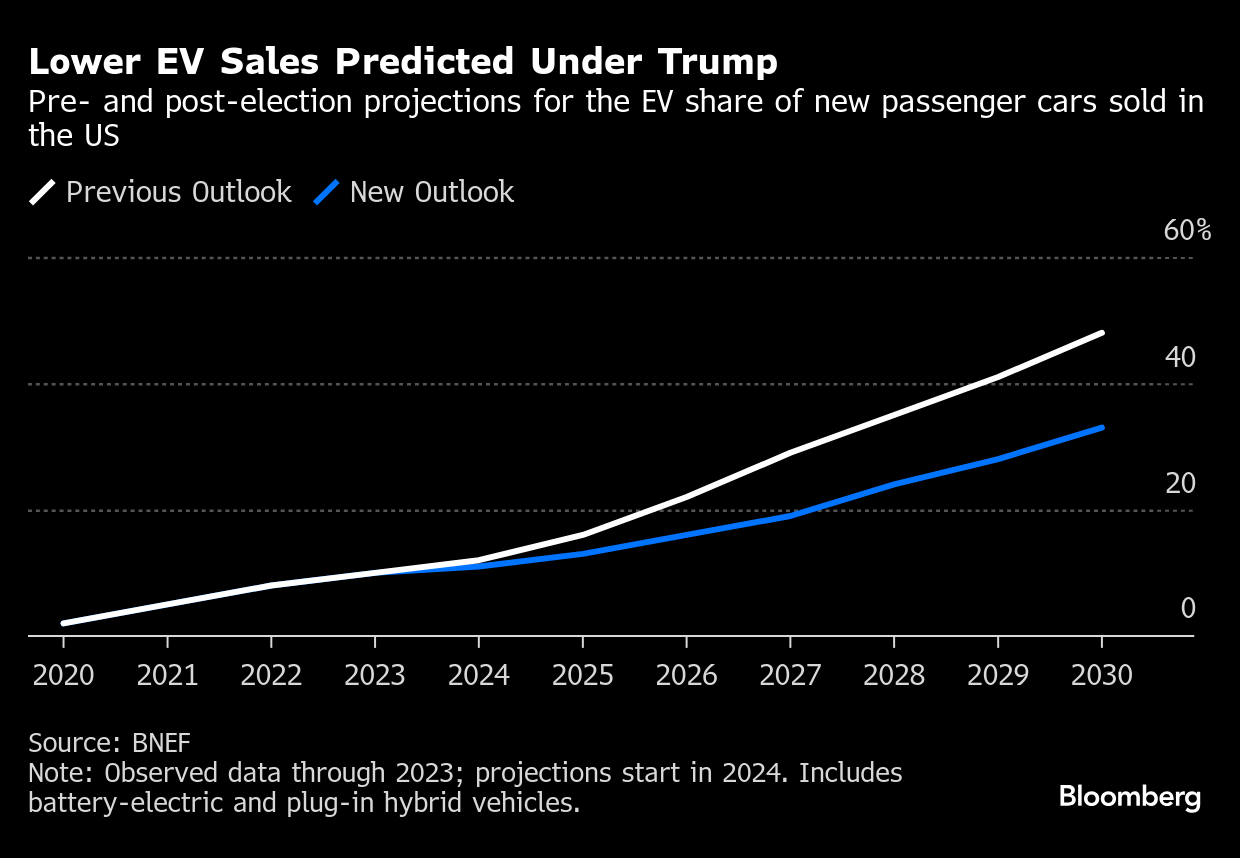

But the impacts of these policies are only starting to be realized, just as Trump is poised to unravel them. “Even if you have people buying electric vehicles, or heat pumps, it takes a long time for that to accumulate into meaningful changes in emissions, because a small number of people each year are turning over their equipment in a much, much larger fleet,” Kaufman says.

Experts still anticipate a growing number of new car sales to come from EVs in the future, but the rate at which that share will grow is expected to decrease. BloombergNEF cut its projections for the EV share of new passenger vehicle sales in 2030 from almost 50%, before Trump won the election, down to 33%.

Consequently, experts are pessimistic about what the next four years may bring. While it’s unclear exactly how much of Biden’s climate legacy will be undone, Pizer says, there’s little doubt that climate policies won’t advance or get stronger. “Time is being lost,” he says.

Listen on Zero: Abandoning Green Transition Is ‘Economic Malpractice’

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.