Qatar’s Carbon-Neutral World Cup Is a Fantasy

(Bloomberg) -- Twelve years ago, when Qatar successfully bid to host this year’s men’s FIFA World Cup, its organizers made the eyebrow-raising promise that their edition of the tournament would be carbon-neutral. Qatar was not the first World Cup host to make such a claim — that distinction belongs to Germany in 2006 — but as a tiny, oil-rich country on a desert peninsula in the Persian Gulf, its net-zero promise seemed to take greenwashing to a new extreme. On a land mass smaller than the state of Connecticut and with a population of about 3 million, Qatar had very little of the infrastructure needed to put on a World Cup — yet planned to build seven stadiums and host more than a million visitors without contributing a single kilogram to global carbon emissions.

When the tournament’s organizers — a triumvirate made up of FIFA, the World Cup Qatar 2022 LLC (Q22), and the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy (SC) — released its greenhouse gas accounting, the report did little to quell doubts. Their calculations, prepared by the Swiss carbon management firm South Pole, set the total emissions for the World Cup at 3.6 million metric tons. But independent researchers at the watchdog group Carbon Market Watch and the Paris-based carbon-management startup Greenly say this is an undercount. Greenly’s own assessment puts the total emissions for the event at 6 million tons, roughly equivalent to a year’s worth of emissions from 750,000 US homes. Greenly CEO and Co-Founder Alexis Normand calls the 2022 World Cup “the most emissive ever.”

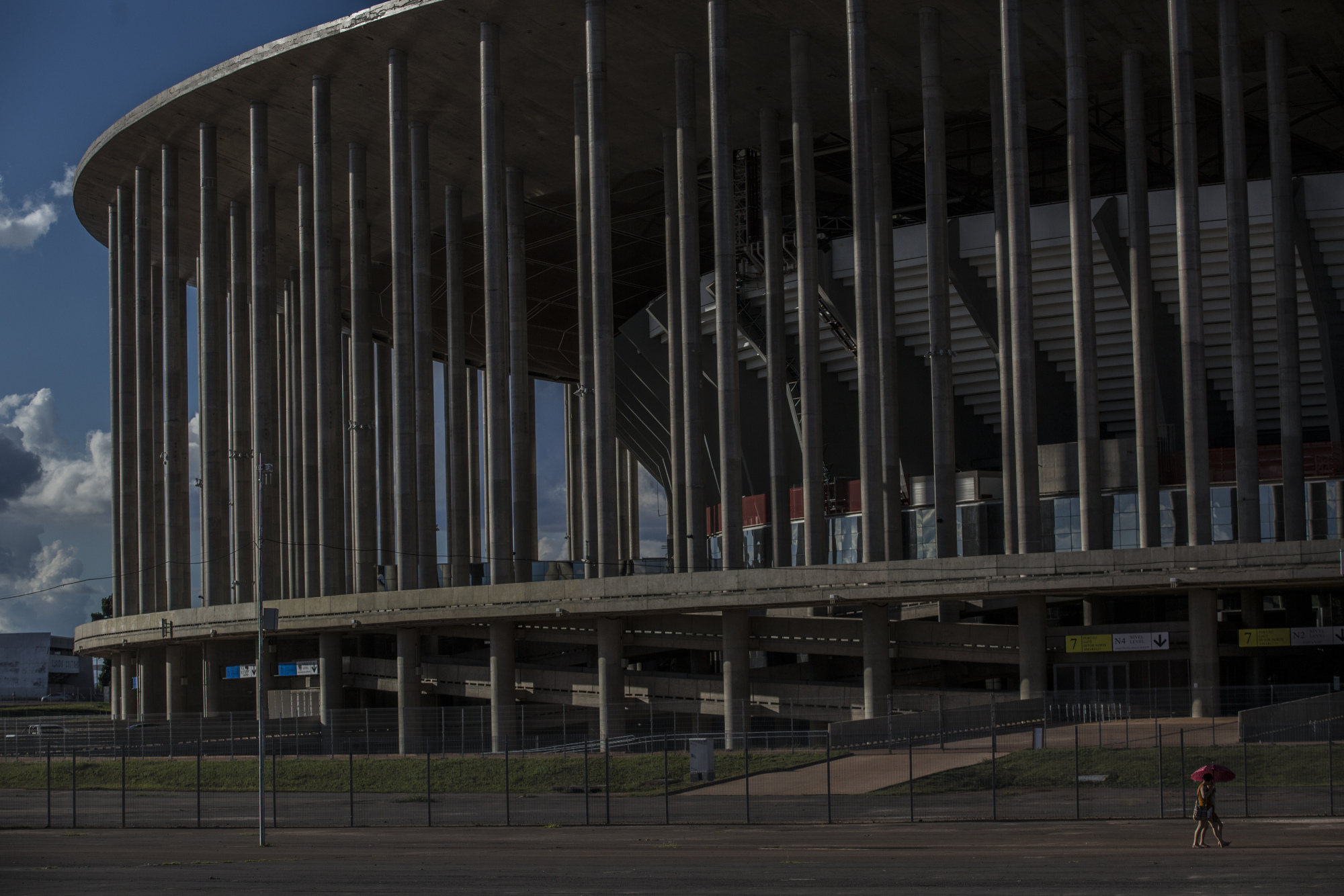

The most glaring flaw in Qatar’s math, as Carbon Market Watch outlined in a report earlier this year, is an underestimate of the emissions associated with its stadium-building. To accommodate the World Cup’s 64 matches, beginning with Qatar vs. Ecuador on Nov. 20 and ending with the final on Dec. 18, the host nation built seven new stadiums. One of them, aptly named Stadium 974, is made from 974 shipping containers and will be dismantled when the tournament is over. The other six are set to remain. In accounting for their carbon footprints, Qatar’s organizers anticipate that these stadiums will find meaningful use for decades to come and so assign them only a small fraction of the emissions associated with their construction.

Recent history suggests this is a fantasy. Many of the stadiums left over from World Cups in Russia, Brazil and South Africa are now white elephants — and all of those countries have populations many times greater than Qatar. “It's just extremely unlikely that Qatar would have ever built these stadiums without the World Cup,” says Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer at Carbon Market Watch. “And it's also very unlikely that they will be used efficiently for the next 60 years.”

Under a scenario projecting medium-to-high emissions, Qatar can in 60 years expect average temperatures to be 4C hotter, with 62 days a year reaching hotter than 45C (113F), compared with less than one a year in the past decade.

A proper accounting of the stadiums, Carbon Market Watch estimates, would boost the emissions attributed to them by about 1.4 million tons, or nearly 40%. This higher total is roughly the emissions that a coal-fired power plant generates in 16 months.

In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for the SC said it is “on track to hosting a carbon-neutral World Cup” and that its accounting methodology is “best in practice” and “designed to be based on actual activity data, after the FIFA World Cup has concluded.” The spokesperson said the organization is “working to ensure there will be no ‘white elephants’ after the tournament by developing legacy uses for all the tournament venues.”

Even if one accepts Qatar’s stadium accounting, its plan to offset remaining World Cup emissions is also deeply flawed. So far, according to disclosures from the Global Carbon Council (GCC), which the tournament’s organizers helped create in order to identify and verify offsets, Qatar has purchased carbon credits from three renewable energy projects in Turkey and Serbia, totaling fewer than 350,000 tons of CO2 equivalent.

Those two wind farms and one hydro plant would exist without the funding, according to Carbon Market Watch. “These are cost-competitive on their own. They sell electricity. They make money from that,” says Dufrasne, “so buying credits from these projects doesn't really impact emissions. You're basically handing out money to someone who was going to do that project anyway.”

The SC said that it has already secured “a minimum of 1.5 million credits” from the GCC and says further details will be forthcoming. “These will be delivered across a number of projects in Qatar and beyond, each of which will cut emissions in different ways,” the spokesperson said.

But while there are better versions of carbon offsets, the idea of using them to declare a World Cup, or any event, carbon-neutral is inherently flawed. It suggests a precision in carbon accounting that is not practical and perpetuates a blinkered understanding of how climate change works. “It’s a Mission Accomplished claim,” says Dufrasne. “It sends the signal that we can continue to live with the kind of economy and habits that we have today.”

BSR, a consultancy and global business network focused on corporate sustainability, has advised companies not to claim events are carbon-neutral at all. “We also don’t recommend them doing so about facilities, or products, because these are really difficult to prove,” says David Wei, a BSR managing director.

Such claims also tend to distract from the only net-zero goal that matters: the planet’s. It is not possible to unburn the fossil fuels that it takes to build stadiums and “fan villages” or to fly to Doha or dock cruise ships in the Persian Gulf. Nor is it possible for every such contribution to global emissions to be offset — even in the most ambitious scenarios for the proliferation of green tech and carbon capture.

“No one’s carbon neutral until the whole world is carbon neutral,” says Normand. “There aren't enough projects to offset everything. Otherwise, we'd have fixed climate change already.”

In an emailed statement, a FIFA spokesperson said it rejects the idea that carbon neutrality claims are counterproductive and said the 2022 World Cup’s net-zero target has been a “very strong motivation” for organizers to focus on climate action. “FIFA is very much aware of the seriousness of the climate crisis and of the complexity of properly managing its climate action and communication efforts,” the spokesperson said. “At no point is FIFA’s intention to distract its attention from the middle-term goal of reaching net-zero emissions.”

In a paper published in Tourism Management earlier this year titled “Peak event: the rise, crisis and potential decline of the Olympic Games and the World Cup,” researchers in Switzerland and New York outline the steep growth of mega sports events over the past 130 years and argue that their trajectory is unsustainable. In order to avoid collapse, they write, the World Cup (and Olympics) will need to adapt and begin ratcheting back the size of their spectacles.

“It fundamentally has to get smaller, unfortunately,” says Sven Daniel Wolfe, a researcher at the Institute of Geography and Sustainability at the University of Lausanne and one of the paper’s authors. “It's time that we disabuse ourselves of this notion that we can innovate our way out of the catastrophe that we're heading towards.”

Yet there are lots of reasons to keep holding World Cups. Beyond the sporting spectacle, which itself brings joy to billions, it is a month-long mingling of people from all over the world. Friendships, marriages, business deals and diplomatic ties are all formed at World Cups. “The schmoozing aspect is very important,” says Wolfe. “Who knows what kind of wars and conflicts have been avoided through this kind of sports diplomacy?”

So how do you keep all the good of the World Cup — the display of talent and athleticism, the memory-making, the peaceful expressions of national pride, the whole celebration — without hastening global warming? What does a climate-conscious tournament look like? Is such a thing even possible?

One simple thing FIFA could do to dramatically lower the climate impact of future World Cups would be to put an end to stadium building. For the 2026 World Cup, to be jointly hosted by Canada, Mexico and the US, an expanded field of 48 teams will be playing in 16 pre-existing stadiums across the continent. Making a model like this permanent would avoid white elephants and eliminate a major source of potential carbon emissions (though spreading the event across such a large area introduces its own set of problems).

“The idea of building new infrastructures is lunacy,” says Wolfe. “We have more than enough world-class stadiums in amazing cities around the world that we could use as existing hosts.”

FIFA’s spokesperson says that while it tries to use existing infrastructure as much as possible, building plans vary according to the circumstances of the hosts and any new facilities have to meet “clear and stringent” requirements for sustainable building. “Many countries still have a need for sport infrastructure to be built and, like in the case of Qatar, such venues are central elements to the country’s own vision and development plans,” FIFA says.

It’s true that limiting the World Cup to existing stadiums would lock in the advantages enjoyed by large, developed nations that have historically contributed most to greenhouse gas emissions. The US or Germany or China could easily host every World Cup, but why should they be allowed a monopoly on the prestige it bestows? To exclude large parts of the world from future tournaments likewise runs counter to growing calls for climate reparations.

Yet there are ways to work around this inequity. Wolfe, for instance, suggests a variation on the splitting of host duties, with one country supplying the infrastructure and another serving as “cultural host.” Matches could be played in stadiums across, say, Germany, while Angola, as titular host, takes charge of the logistics, pomp, circumstance, and profits. Angola’s head of state would control the limelight and the luxury boxes and, instead of ghost stadiums, the country would be left with money, expertise and a boosted global image.

“There would have to be some kind of climate-justice-oriented profit sharing baked into it,” says Wolfe.

FIFA could also open the playing field for more host countries by simply adjusting its standards. The organization’s current stadium guidelines run to nearly 300 pages and require, among other things, that World Cup match facilities include at least 40,000 seats, a player dressing rooms of at least 80 square meters with a 4.5-meter-wide tunnel to the field, space for a 2,000-square-meter broadcasting compound, a VIP lounge for 500 people and a “VVIP” lounge for at least 100. Stadiums are also supposed to be oriented such that the sun is behind the main stand at match times to avoid issues with glare during TV broadcasts.

The impetus behind many of these standards is to maximize match-day revenue and make sure that stadiums provide appropriately grand backdrops for the broadcasters paying billions for the right to show the games. But dispensing with some of the rules would expand the list of existing stadiums that could be used and make hosting the games feasible in more places.

Infrastructure is not the only problem that will require hard choices. The largest single source of emissions in Qatar’s accounting — at more than 1.7 million tons — is international air travel, and there is little that can be done to reduce this toll without cutting back on long-distance flights. Wolfe and his colleagues suggest this, too, may be an unfortunate but necessary measure. The delayed Summer Olympics in Tokyo in 2021, for which the coronavirus suppressed the number of visitors, provided an accidental demonstration of how limiting travel can lower the carbon footprint of mega events: Pandemic restrictions led to an 80% reduction in emissions due to travel by event personnel.

The upside to Qatar’s small size, as both the organizers and FIFA point out, is that it minimizes the need for internal travel during the World Cup. Doha’s rapid transit trains and a fleet of 800 new electric buses, the SC says, will be the primary means to ferry fans between venues. These gains are undercut, however, by a 168-flight-per-day shuttle service set to carry spectators to and from neighboring gulf states — a service that Greenly estimates will add more than 80,000 tons of C02 emissions.

Once every means to cut emissions has been exhausted, there are investments that Qatar and future World Cup hosts could make to truly help offset what remains. The best options, says Seth Wynes, a postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University in Montreal who researches climate change, are those that need the support most, such as direct air capture, an expensive new technology that injects greenhouse gases underground. Scientists say this will be an essential supplement to weaning our economies from fossil fuels. Likewise, sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are a fledgling industry that, with more subsidies, could mitigate the climate impacts of air travel. Helping to fund these efforts, says Wynes, would show that the World Cup was “serious about being carbon neutral.”

Before any of these measures, though, Wolfe says organizers have to be more candid about what the World Cup is for. FIFA and bid committees tend to pitch the event as a catalyst for economic and civic development, claims that are routinely overblown. In some cases, the World Cup proves a financial burden for the hosts.

But the tournament does not need to be an engine of growth to be worthwhile. Wolfe compares it to hosting a house party: You buy the food and drinks, rearrange rooms, and clean up after — not because you expect to make money, but because it’s a good time and you want other people to like you. “Let’s be more honest about the fact that it’s an expensive party,” he says. Dispensing with any other pretense allows for a more realistic cost-benefit analysis. A party might still be worth it if you need to replace the living room carpet afterwards, but probably not if it burns the house down.

Building a single stadium from shipping containers or planting 16,000 trees around the country, as Qatar also plans to do, are laudable efforts, but they are not enough to keep the party from burning the house down and do not live up to a claim of carbon neutrality. Those 16,000 trees — once they’re mature — are enough to offset the annual carbon emissions of about 11 Qatari citizens, or 24 Americans.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.