Germany’s Ballooning Subsidy Costs Show Challenge of Going Green

(Bloomberg) -- Germany is buckling under the weight of ballooning renewable energy subsidies, raising questions for governments across the world about how long they can afford to prop up green investments.

While the country’s decades-old support measures have been key to cutting global production costs, they’ve made clean energy projects so appealing that power prices frequently tumble to low or even negative levels on days with too much sun or wind. Since the government covers the difference to ensure producers’ guaranteed returns, subsidies are set to hit €20 billion ($21.7 billion) this year, double what was initially set aside.

The trend — dubbed “electricity madness” by the nation’s biggest tabloid — comes at a sensitive time for taxpayers, who’ve experienced the fastest inflation in decades in recent years and will need to endure public spending cuts in other areas as the government wrangles to clean up its budget.

Renewables producers earned billions during the energy crisis that drove up power costs, and continue to do so via subsidies even after prices have dropped.

“We need to turn the entire regime upside down, otherwise it will no longer be financially viable,” said Nadine Bethge from the nonprofit Environmental Action Germany.

The issue facing Europe’s largest economy foreshadows what will likely become a key policy question elsewhere: can governments afford to stop throwing support at cleaner energies without putting the transition at risk?

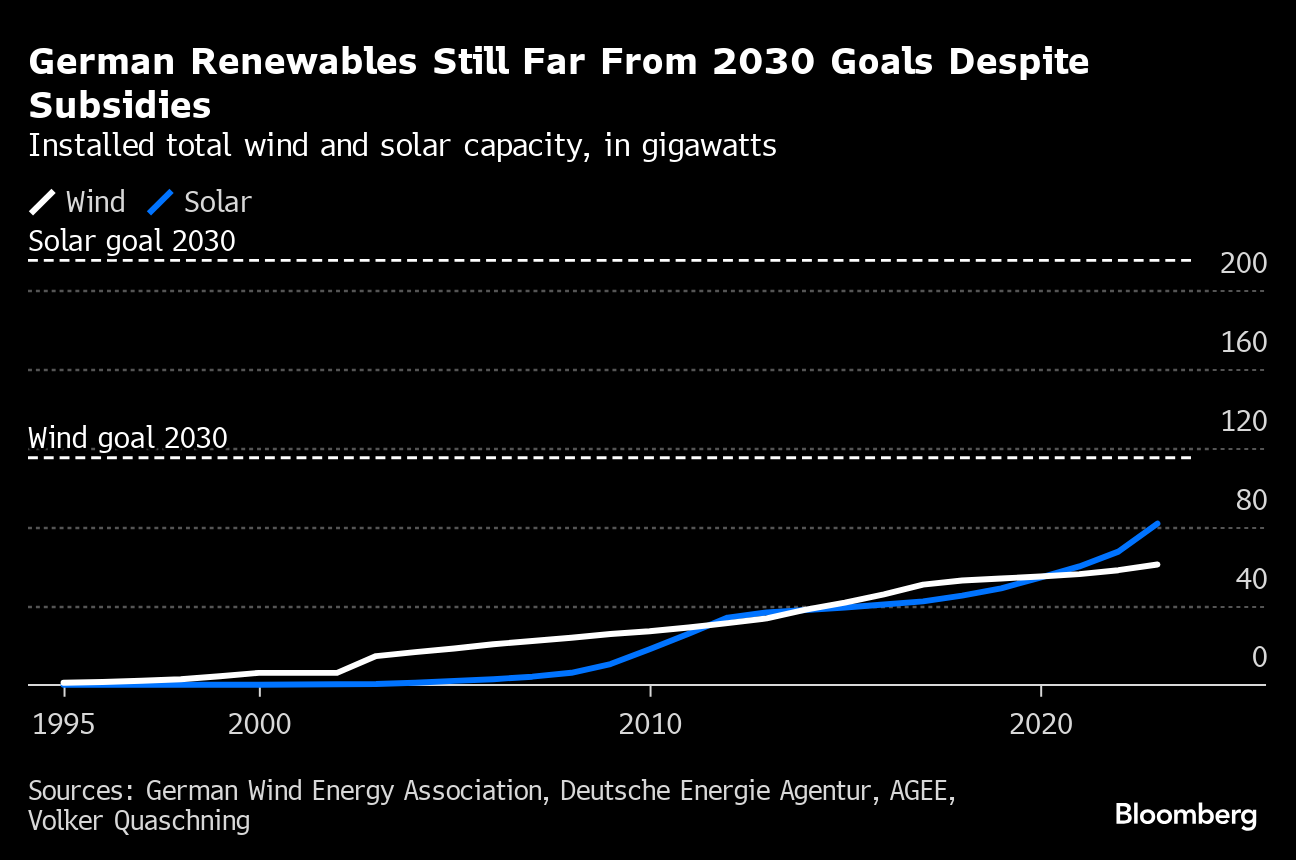

Berlin is already pushing ahead with initial reforms that aim to reduce subsidies, and there are proposals for a broader overhaul based on supporting investment costs, rather than guaranteed prices for output. The emerging consensus is that the original subsidy scheme — designed in the early 2000s — was meant to support fledgling technologies, not ones that now make up more than half of the country’s electricity mix.

“The technology was not witchcraft even then, but it had to become marketable,” said Jürgen Trittin, who was environment minister when Germany’s clean energy scheme was drafted. The state ultimately agreed to set up a renewable electricity subsidy at a fixed price over a 20 year period, “but with the aim of making it competitive.”

A bold revamp could set the tone for the rest of Europe as it heads toward full decarbonization by 2050. Critics such as Simone Peter, president of the German Renewable Energy Federation, worry that a “radical change” will choke off investments or push them into jurisdictions with more favorable conditions.

It’s not the first time Berlin faces calls to reform its subsidies. Since they guarantee a minimum price, the European Commission asked Germany during the energy crisis to also put an upper lid on utilities’ earnings, as is done in the UK and other places.

“This is a very flexible system that doesn’t exist in other markets,” said Nicolai Herrmann, director of consulting firm Enervis.

Economy Minister Robert Habeck and lobby groups representing German industry have rejected calls to introduce contracts-for-difference schemes — like those used in the UK — amid fear they might stall investments. Habeck has instead advocated for a capacity mechanism, in which a certain fixed output is put on tender, and which should first be tested in the market.

Renewables “will continue to be subsidized, but in such a way that is increasingly market-efficient,” Habeck told reporters last month.

In addition to a lack of clarity over future support, one concern is that banks will be hesitant to finance renewable investments if there’s no certainty on long-term profitability. Such projects are far more attractive if they have a locked in price for the power they deliver, said Trevor Allen, Head of Sustainability Research at BNP Paribas Markets 360.

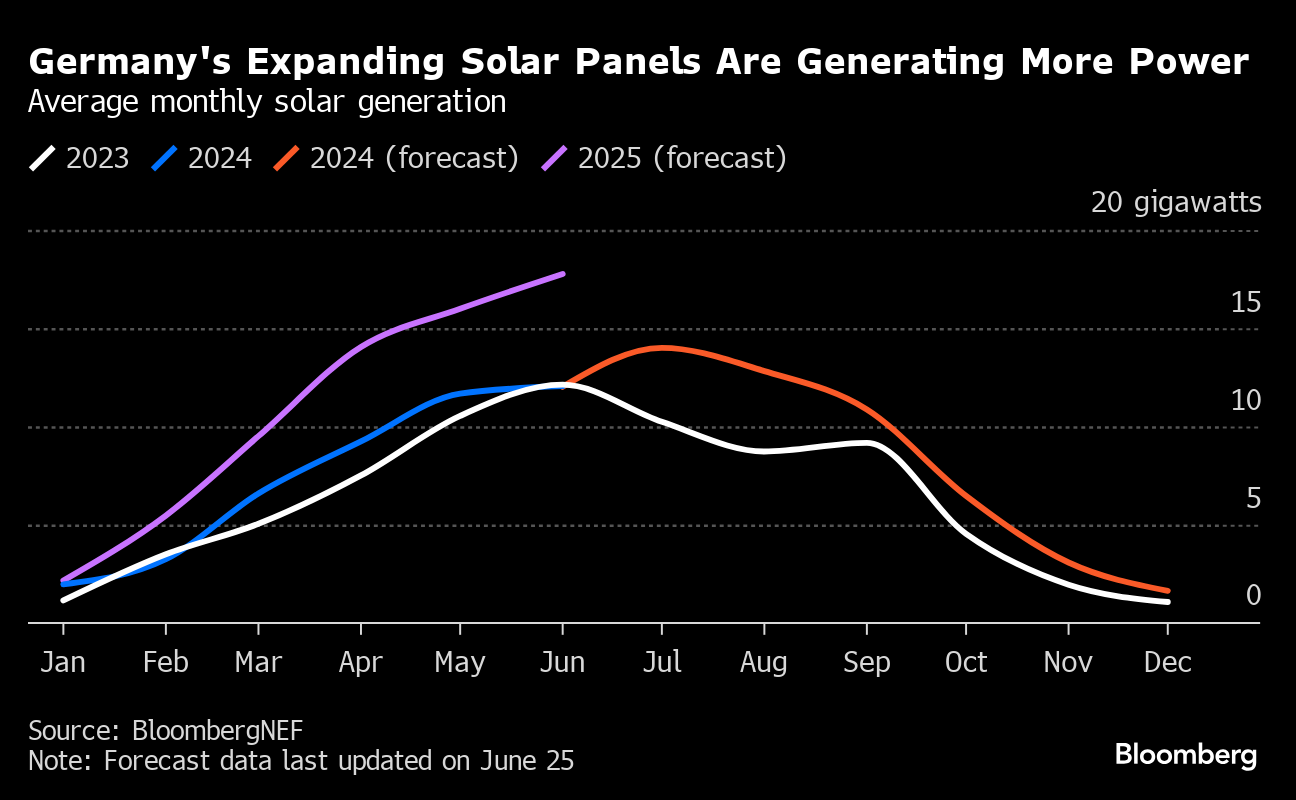

That’s not an issue for all types of investments: Offshore wind has become so lucrative that developers are willing to pay billions for seabed development rights. For onshore wind and solar it’s more difficult due to geographical limitations. Despite adding massive photovoltaic capacity last year, Germany’s actual solar output dropped by 1.3% amid cloudier weather.

Another issue is that any changes to current subsidies would likely have to go through a lengthy EU approval process, according to Thomas Schulz, German Head of Energy at Linklaters LLP, and it’s unclear whether they would be cheaper.

Meanwhile, the decline in wholesale power prices has already started to hold back projects falling outside of the existing framework — for instance because of their size — indicating there might be little appetite for investors if support is reduced.

“Solar developers are now all taking their foot off the gas when it comes to investments because the achievable revenues for market-based PV systems have fallen,” said Thorsten Kramer, chief executive of LEAG, a large coal miner which aims to install seven gigawatts of renewable plants by 2030.

One financing tool that might offer some hope for continued expansion involves forming direct contracts with industrial customers. Even though Germany is now Europe’s second-largest market after Spain for power purchase agreements, they only cover a tiny fraction of 3.6 gigawatts so far.

One example comes from the east German village of Witznitz, where Europe’s largest solar park was inaugurated this month, selling power directly to Shell Plc and Microsoft.

“We are able to install solar systems today at the given costs,” said Wolfgang Pielmaier, a shareholder of the project. “It’s high time that renewables should no longer reach out to the state.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.