Giant Power Cables Linking Europe Are Growing Source of Tension

(Bloomberg) -- The collapse of Norway’s government this week brings into focus the hundreds of cables transporting electricity across borders in Europe and how they’re being transformed into political weapons.

A dispute about exports of Norway’s cheap power is partly behind the government breakdown. Elsewhere, Swedish Energy Minister Ebba Busch said she was “furious” with Germany in December as exports to Europe’s biggest economy caused higher prices for the Nordic nation. In France, the far right party wants to stop free trading across borders altogether.

Europe’s electricity system is the world’s largest interconnected grid linking nearly 600 million citizens, according to energy think tank Ember. It embodies the spirit of solidarity in the European Union and sharing resources with your neighbors. The rise of right-leaning parties with an emphasis on inward-looking policies is disrupting the harmony.

“We will have national control,” Norway’s Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Store said at a press conference Friday. “It is Norwegian democracy that shall decide over Norway’s power resources.”

Interconnectors are supposed to work based on price not politics. The idea, is that power flows to the more expensive market, providing more supply and reducing costs in that country. The links work best between countries with different energy mixes, for example France with its huge nuclear fleet and the UK with its supply of wind generation.

The rise of intermittent renewable sources of power has revealed the downside to these links — a shortage in one country often leads to soaring costs next door too.

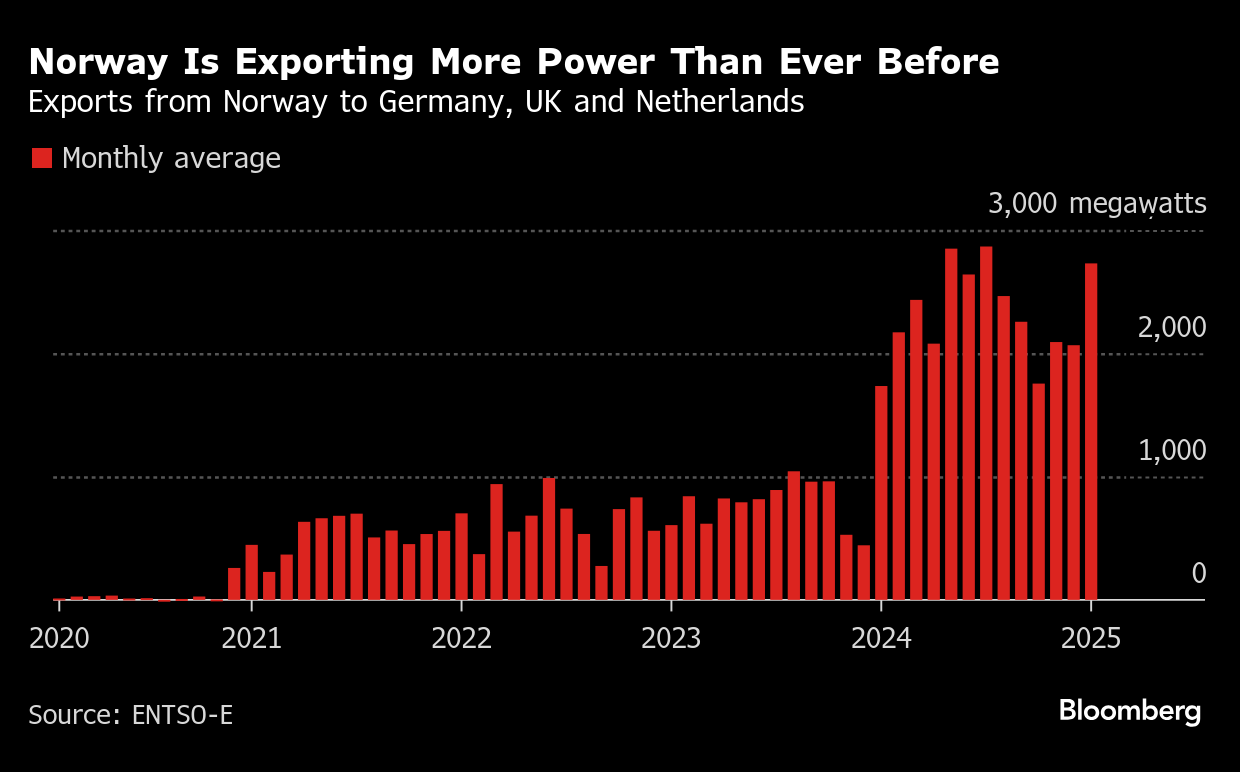

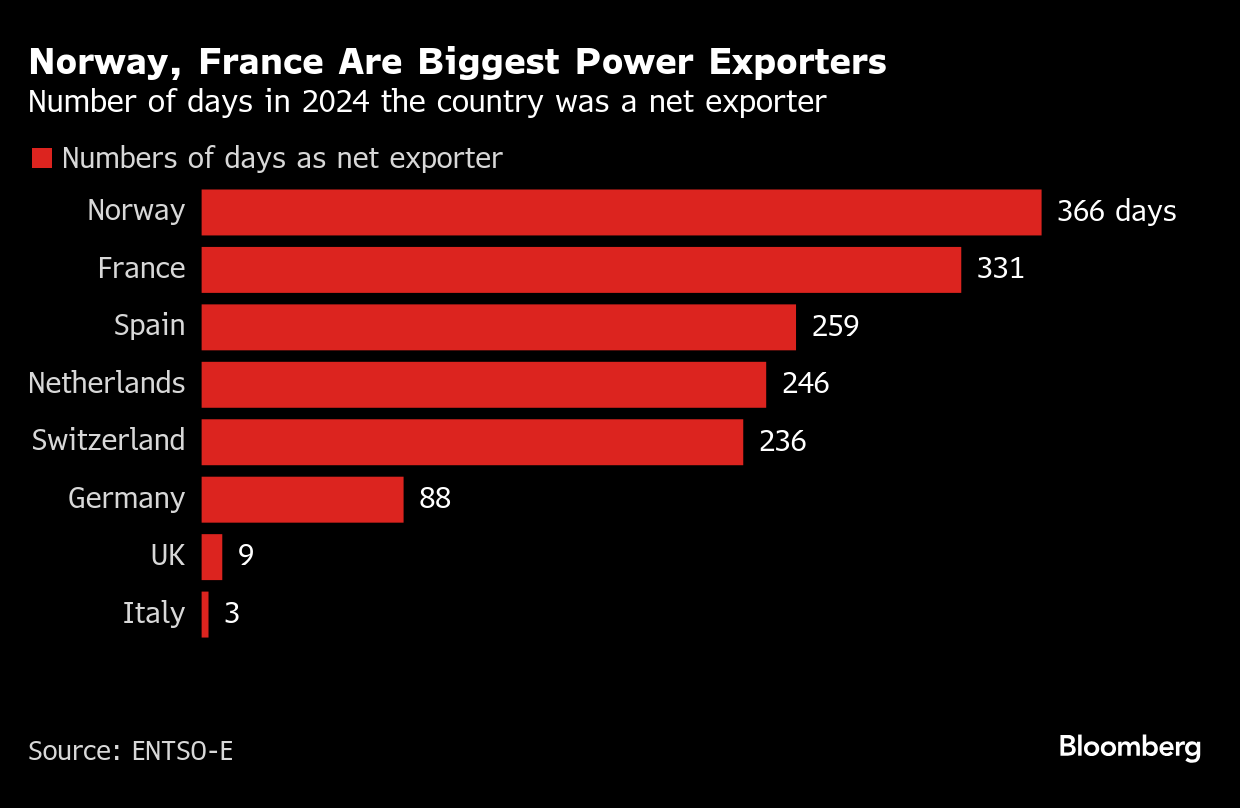

The debate in Norway has been brewing for some years, with soaring prices in north-west Europe stoking discontent. The nation was Europe’s third biggest electricity exporter last year and sales to the UK and other markets have caused price spikes, particularly in the south of the country. Higher bills for Norwegians, make it a political issue.

Though Norway isn’t an EU member, it is part of the single energy market. Under the rules, countries aren’t allowed to curtail flows to neighbors for prolonged periods.

The unity of Europe’s energy market was tested during the energy crisis. Would countries be willing to export electricity and risk pushing up bills even further at home? The framework largely held up but the cracks started to show prompting the Norwegian government to mull a control mechanism to limit exports.

Whether or not to replace aging cables in Norway that are approaching the end of their operating lives “has become a huge political debate and a very populistic debate,“ said Lars Ove Skorpen, director Power and Renewables Energy at Pareto Bank ASA in Oslo.

Norwegian Premier Store does say he wants to work with other Nordic countries to address fluctuations and instability in the power market.

“If we lift our gaze and look forward to what is happening around the North Sea, there is a strong emphasis on renewable power from all countries,” he said. “But then every country has to sit down and consider what is their share of such a possibility and there is no one who is going to do something that is not in their interests.”

In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally wants to take back control and replace free trading with bilateral or multilateral contracts with neighboring countries. France and its 57 reactors are the backbone of the European power system. If politicians can find a way to keep more of that cheap supply at home, it might even attract more manufacturing and industry, providing an economic boost.

The UK is one of the main beneficiaries of France’s surplus. Since closing it’s last coal power plant last year, the country is increasingly filling the gap with imports and now relies on nine interconnectors. By 2030, it hopes to return the favor and aims to become a net exporter after boosting wind and solar generation.

The European Commission is sticking to its strategy and pushing for even more integration. The bloc will allocate almost €1.25 billion in grants from the Connecting Europe Facility to 41 cross-border energy infrastructure projects.

At a national level, there are some signs of splintering. Sweden last summer rejected plans for another cable with Germany. Energy minister Busch at the time blamed the neighbor’s “inefficient” market saying it would risk even higher prices if they became further linked.

Germany closed its nuclear reactors and hasn’t been building enough new capacity to replace it so it relies heavily on imports. Industry in Europe is buckling under the weight of high energy prices with some firms choosing to relocate operations to the US or China.

“There are clear European benefits of interconnectors, but governments think differently about it and want to protect their markets,” said Alexander Esser, head of the Nordic region at Aurora Energy Research.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More utilities news

Who Gains, Who Loses as India Doles Out $12 Billion in Tax Sops

UK-Morocco 2,500-Mile Power Link Seeks Political Champions

Tesla Buoys Investors With Growth Pledge, Robotaxi Rollout

DeepSeek’s Promise of Energy Efficiency Darkens Power Stocks

DeepSeek’s AI Model Just Upended the White-Hot US Power Market

Diversified Energy to Buy Maverick to Expand US Oil Asset Base

How Rachel Reeves Decided UK Needs to Bet Big on Economic Growth

AI-Driven Power Boom Will Drive Demand 38% Higher on Top US Grid

Storm Éowyn Leaves Thousands Without Power, Grounds Flights