Scholz Leaves Germans With Worst Economic Blues in a Generation

(Bloomberg) -- Olaf Scholz is heading for the worst election defeat of any German chancellor, and his poor economic track record is one major reason.

If polls are correct about the drop off from Scholz’s 2021 victory – and the numbers have barely moved during the three-month campaign – then his Social Democrats will face a bigger loss than under any German leader since the Federal Republic was set up in 1949. The projected outcome of about 15% of the vote would also be the lowest for any incumbent.

A lot of his problems come down to the economy. Not since Gerhard Schroeder’s narrow defeat in 2005 has that featured so prominently in an election. Back at the turn of the century, as now, the country was labeled the “sick man of Europe.”

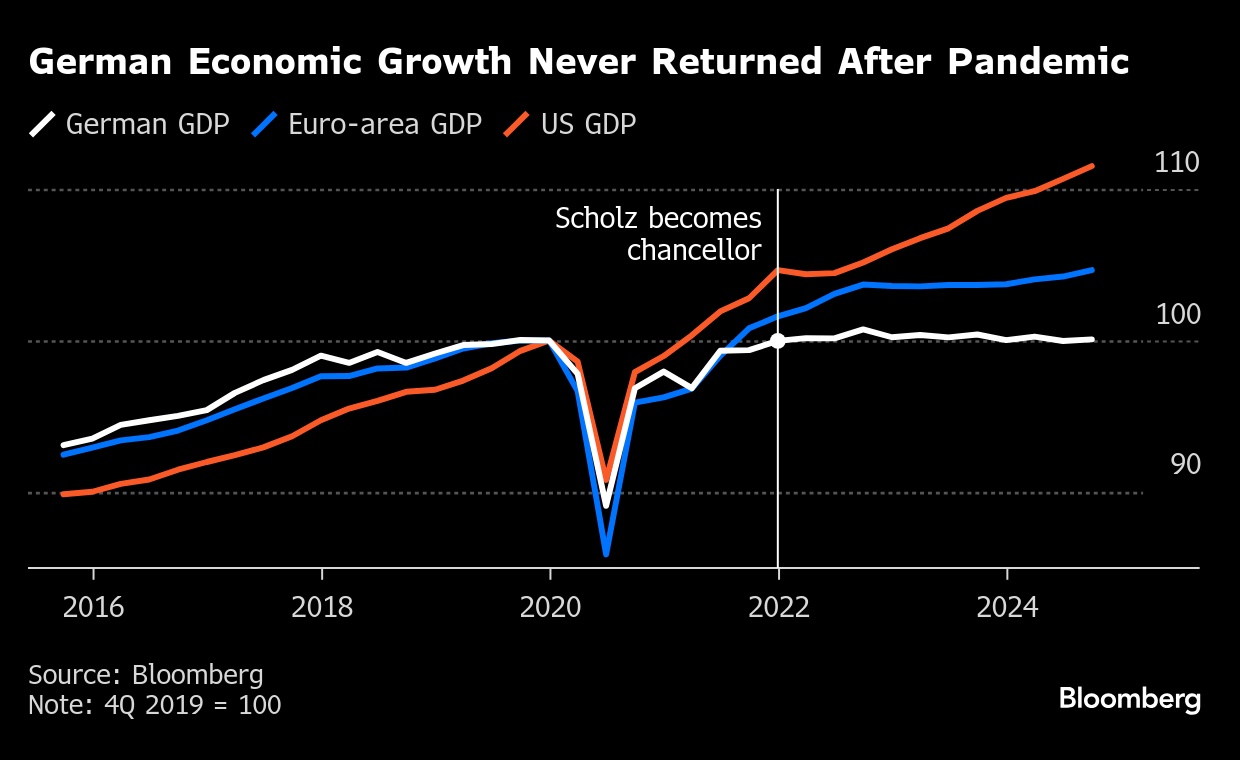

Germany’s failure to bounce back from the pandemic in the way that the US and other peers did has been the defining narrative during Scholz’s three-year term. Fixing Europe’s biggest economy after two years of contraction will be one of the next government’s key challenges.

Amid soul-searching on how to address deep-seated troubles recognized as largely homegrown, the 66-year old chancellor will probably be succeeded by his conservative opponent, Friedrich Merz, at the helm of a new coalition government.

Growth has long been a dominant topic in the campaign for the Feb. 23 election. While attention has shifted to migration, voters still see the economy as the nation’s second-biggest problem — and it’s even playing a bigger role in individual ballot-box decisions than refugees and asylum, according to a poll by public broadcaster ZDF.

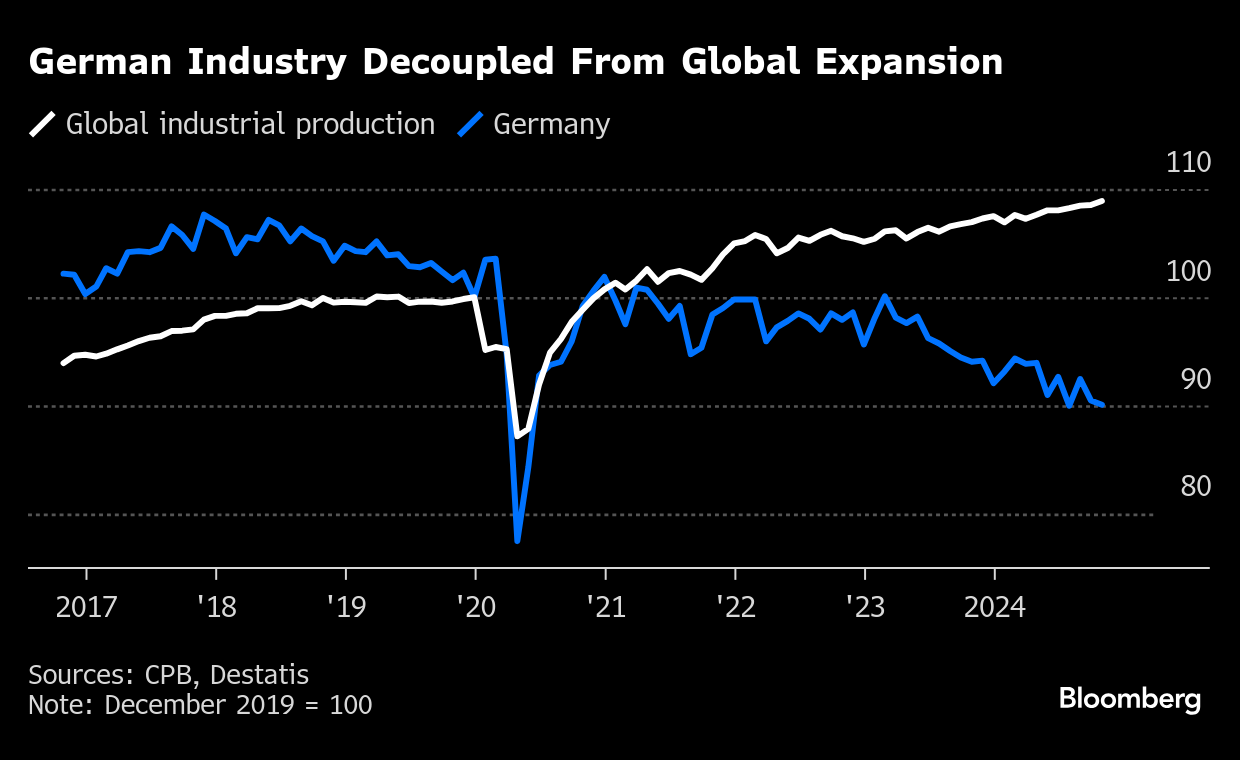

The malaise stems primarily from manufacturing, which makes up a bigger share of output than in many peers. During the pandemic, when consumer demand swung quickly toward goods while restaurants and other services shut down, this worked in Germany’s favor.

But soon after, supply-chain problems, surging costs for energy and labor, as well as high interest rates, created strong headwinds. With that backdrop and facing intense Chinese electric vehicle competition, Volkswagen AG, Germany’s biggest automotive producer, is cutting 35,000 jobs.

The decline in industrial production there contrasts with the global trend. According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, this decoupling signals that German companies have become less competitive.

The country’s record trade surplus with the US makes it vulnerable to a further hit if President Donald Trump follows through on his threat of tariffs against the European Union. Bloomberg Economics reckons he could target levies on cars and industrial machinery — exports Germany particularly relies on.

Manufacturing has struggled with the energy hit from the war in Ukraine. Politicians in Scholz’ coalition argued that the strong reliance on Russian energy imports meant that Germany suffered more from the disruption to natural gas flows. While initial fears of a deep recession didn’t come to pass, the economy still faces higher costs as a result.

The government did have some success in finding alternative sources to Russian energy. Germany not only successfully fast-tracked the expansion of liquid natural gas terminals, but also cut a lot of red tape to spur renewables.

As a result, the nation experienced the fastest growth of solar energy in Europe and rapid deployment of wind turbines. Onshore wind received record approvals and auction awards, further raising the prospect of an accelerated expansion.

The problem now is that grid expansion can’t keep track with the added capacity, so part of that green energy remains unused. After exiting nuclear power two years ago, the nation also lacks backup capacity for periods of “Dunkelflauten,” when there’s no wind and skies are overcast.

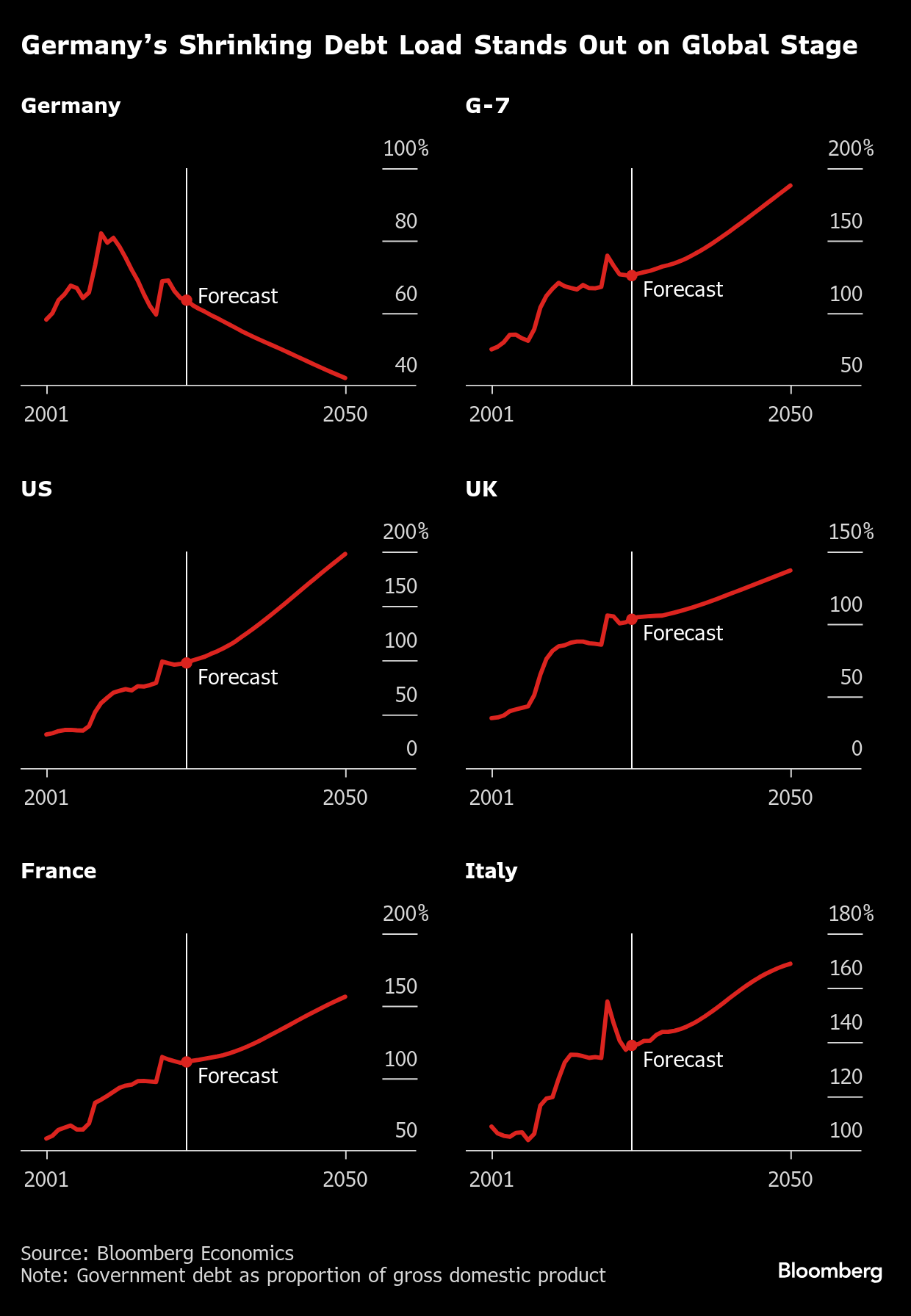

Aside from energy, the dominant policy debate has been over government finances. With growth falling behind, public coffers became increasingly stretched — eventually leading to a coalition split and early elections when politicians couldn’t agree on a budget for 2025.

Germany has by far the lowest borrowings in the Group of Seven. The opposition CDU/CSU wants to stick to the constitutionally enshrined debt brake, though Merz has signaled some openness to reform. The SPD wants to loosen the rule to enable more public investment and stimulate demand. His coalition partner, the Greens, also favor a looser limit.

Pressure to spend more has intensified, with crumbling infrastructure and the shortcomings of the military now increasingly difficult to ignore. The German Council of Economic Experts criticized the government late last year for not devoting enough funds to “future-oriented” areas such as education and transport.

The potential costs are dizzying. The German Economic Institute estimates that an extra €600 billion ($625 billion) may have to be dedicated over the next decade to the energy transition, roads, railways, the education system and other issues. Dezernat Zukunft, a think tank, even sees a need to spend an additional €800 billion between 2025 and 2030.

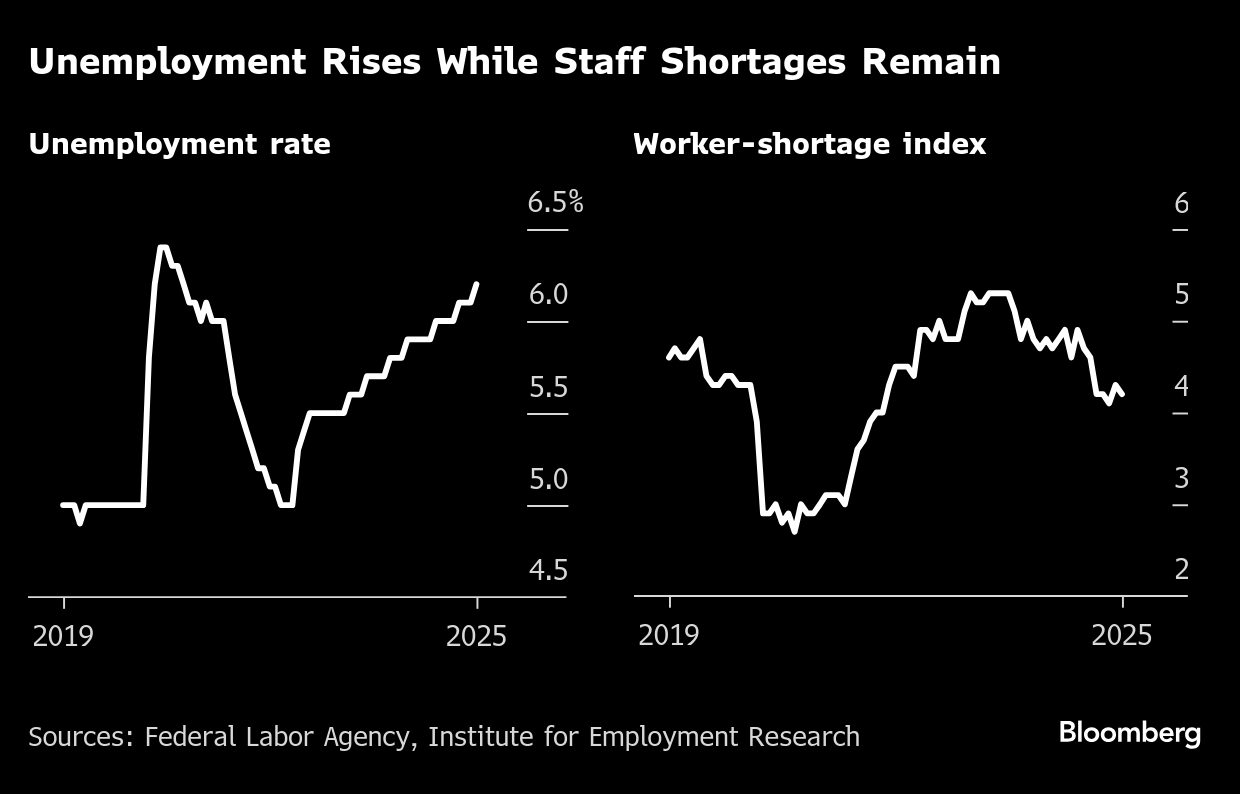

For all of Germany’s arguments about debt and worries over growth, the labor market has been a bright spot. That’s partly because of staff shortages for companies in the aftermath of the pandemic, which made them wary of shedding workers.

More recently however, the weak economy has pushed unemployment steadily higher, though the overall tally is far below the peak of around 5 million that it reached in 2005.

Staff are still missing in areas including hospitality and health care, pointing to a skills mismatch. Adverse demographics mean more Germans will leave the labor market in the coming years, presenting another problem for policymakers.

While Germany’s next leaders face formidable challenges, the good news is that they have the power to change the nation’s trajectory, according to Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel. “Reliable, predictable actions” could foster investment and expansion, he said last month.

“It’s up to the next federal government to implement structural reforms that will increase potential growth again, so that the fears of decline will disappear again,” he said.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More utilities news

Thames Water Takes Business Plan Dispute to Markets Watchdog

Turkish Oil Refining Giant Tupras Shies Away From Russian Oil Due to US Sanctions

Thames Water Under Fresh Investigation by UK Water Regulator

Bangladesh Seeks Full Electricity Supply From Adani Power

European Gas Prices Hit Two-Year High as Supply Fears Intensify

Iran’s Currency Slumps as Hopes Fade on Renewed US Talks

Thames Water Rescue Bidder Doubts Sale Process Feasibility

Edison Probing Retired Power Line as Possible Start of LA Eaton Fire

UK to Eases Rules for Nuclear Plants in Bid to Boost Growth